Red Sparrow, aka Female Prisoner Tatiana Romanova – a review

My elevator pitch for Red Sparrow:

“It’s a Kubrickian-ish Tinker Tailor told from the perspective of From Russia With Love’s Tatiana Romanova by way of Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion.”

Red Sparrow has created a rift. One faction stands opposed shaking its fist angrily at mainstream misogyny. The other faction wilts a little, quietly asserting that Francis Lawrence’s film is an uneven, but generally competent thriller that may actually have something unique to offer.

The general public, however, has been misled about the nature of the film. Expectations can be damning. Luring an audience that feels betrayed by the content creates negative word of mouth. An advertising campaign that sells a movie like Red Sparrow as another Hollywood thriller (it’s like Atomic Blonde because it’s girl spies and stuff!) creates immediate indifference in the moviegoers who might be more willing to meet it on its own terms.

A disclaimer

I should also make it clear, right from the get go, that I do not believe battle lines have to be drawn between gender perspectives. I believe that the effective employment of the aesthetic in question remains a universal concern for discerning fans of both mainstream cinema, genre cinema and beyond. This is not an easy film to defend, but I will try to piece together appropriate and clear-minded words of some kind.

People are violently, viscerally offended by the content of Red Sparrow. I believe they’re viewing the film with miscalibrated expectations. Maybe that’s wrong. Maybe the most violent detractors have the film assessed more clearly, but Red Sparrow doesn’t – or shouldn’t – fall into mainstream genre convention. The minute I made the connection to Shunya Itō’s Female Prisoner 701: Scorpion (1972) I had to question its existence as a big budget Hollywood thriller starring Jennifer Lawrence.

Let’s talk exploitation and frame of reference

For those that haven’t seen the Female Prisoner Scorpion series, they’re stylized revenge films (and part of the Japanese women-in-prison genre made by Toei Company) concerning a woman named Matsu coerced into undercover work by her boyfriend (a crooked police detective) to win the trust of the Yakuza. After she is gang raped, the police detective barges in, busts the Yakuza and discards the battered Matsu, nothing more than a pawn in his political aspirations. After a failed attempt to stab her former lover, she’s sentenced to hard time in a women’s prison and subjected to torture at the hands of her sadistic male prison guards. She ultimately escapes, as if emerging from a chrysalis. The virgin reborn as an assassin, whereby she extracts bloody revenge, including literal emasculation. Itō’s sympathy clearly resides with his strong female character.

In Sight & Sound, Matthew Leyland notes that the feminist reading of the film as a criticism of the oppressive Japanese patriarchal society becomes “hard to reconcile with the sustained, glib emphasis on female torment” – something that has been said about Red Sparrow, just without the benefit of 40-plus years of critical analysis. Though “hard to reconcile” Ito has made a strong case for his film. Going as far as calling it a feminist manifesto, as some have done, stretches credibility however. Creating the ultimate rebel within such a deeply misogynistic society required a figure of female opposition.

The inciting scene of sexual violence, stylized and shot from beneath, reduces viewer proximity to the on-screen action by calling attention to the film as artifice.

Female Prisoner 701 portrays men as filthy, leering animals, and the two rape scenes place very little flesh on display. There’s no shortage of frivolous nudity, but the film also deflects base criticism by using a highly stylized color palette and innovative camera work, transcending its graphic nature and rising above reductive terms such as “Grindhouse” or “exploitation.” The male gaze (and thereby the male viewer) is complicit, and make no mistake it is not celebrated. Recognizing this is an important step in processing the film’s impact as both a piece of exploitation and as a feminist-leaning film.

With regard to Red Sparrow, it’s also important to attempt to define the term “exploitation” – not because I assume you’re unfamiliar, on the contrary, but because it encompasses so many broad and independent factors like budget, theme, graphic content, and intended audience that the determination ultimately lacks idiosyncratic specificity. Exploitation cinema implies many different things depending upon your own cinematic point of reference.

Pam Cook, in her article “The Pleasures and Perils of Exploitation Films,” suggests that exploitation films can be seen “as offering alternatives to the dominant representational system, opening up the possibility of saying something different.” In other words, they’re not beholden to traditional commercial expectations because they do not aspire to attract mainstream sensibilities.

After the inciting rape scene, Ito plays with color and cinematic conventions to denote the emotional transformation of Matsu.

She continues to say that “much of the appeal of exploitation films to the drive-in cinema and student audiences for whom they were primarily intended derived from the knowing way in which they played on audience expectations of narrative and genre, parodying mainstream conventions.” This is an important distinction as it places exploitation in direct conflict with the multiplex. She goes on: “Low budget exploitation scandalises some of the most hallowed canons of film criticism – the assumption that the critic or academic knows better than ‘unsophisticated’ audiences how to judge a good or bad film…” An exploitation film attempts to shock your sensibilities (and undermine critical superiority) by way of uncommon or sensationalized sexual or violent imagery – and as Cook suggests, they also often do so referentially, with a nod toward films of the past or an eye towards undermining genres or conventions of the present.

Despite being released to mainstream cinemas and marketed as a conventional spy thriller, Red Sparrow falls neatly into that definition of exploitation cinema. It does not dare go as far as a film like Female Prisoner 701 because there are dozens of systemic checks and balances in place to make sure that nothing as challenging as Shunya Itō’s landmark film could ever accidentally play at your local multiplex.

And this is how that relates to the Red Sparrow

From this point on, I cannot guarantee a totally spoiler-free conversation due to the required specificity. Proceed at your own peril. I promise not to give away the final act, however.

Red Sparrow attempts to reset our expectations early in the film. Bolshoi ballerina Dominika Egorova suffers a gruesome injury during a performance. Her male counterpart lands on her leg, crushing her tibia. The camera pulls upward revealing the grotesque configuration of her once pristine, virgin body. Virgin as in untarnished by the cold, sterile, and uncivil world outside her isolated Bolshoi bubble.

The opening ballet scene, pre-injury, that also showcases some of the standout costume design found throughout the film.

The film cuts to the hospital. The film’s warm color palette disappears, replaced by sterility. Dominika rushed into surgery. The standard Hollywood film concerned with broad decorum would have skipped directly to a shot of her walking with a cane, a close-up of the 12” scar on her shin. Red Sparrow does not offer anesthesia in the form of semiotics – injury to visual post-surgical evidence. Lawrence allows his camera to linger over the horror in the space between the cuts. The lifeless pronate ballerina, the open gaping wound. Surgeons drill her shattered bones back together. An unsettling brand of body horror brought to you by the coalescence of mangled flesh and the aural tremors of power tools.

Exploitation films do not avoid conflict with expectation – they thrive on it. For revenge films especially, the audience must experience these horrors so that they may morally justify the ultimately extreme actions taken by the protagonist. Without proper justification, the film ebbs closer towards repellent nihilism (see something like I Spit on Your Grave, which Roger Ebert called a “a vile bag of garbage”) or the Death Wish sequels (“morally repugnant”). The torment of the protagonist feeds our sympathies.

But the balance

A director must frame or balance any exploitative sexual violence or exhibition with an equal or opposite force. This is where I’ve noticed the violent criticisms made against Red Sparrow take exception to Francis Lawrence’s leering camera and the use of rape as a frivolous inciting action. I see reason for objection and wholeheartedly respect the criticism. Rape has become a lazy narrative device for both film and television written or produced by any gender. While I do not entirely disagree with this criticism of Red Sparrow, I also believe that this reaction speaks to the provocative and calculated ways Lawrence and screenwriter Justin Haythe approached – albeit imperfectly – a narrative development that they saw as essential to Dominika’s character.

But we’ll return to that in a minute. I want to first put Dominika Egorova’s character into some kind of cinematic and perhaps historical perspective.

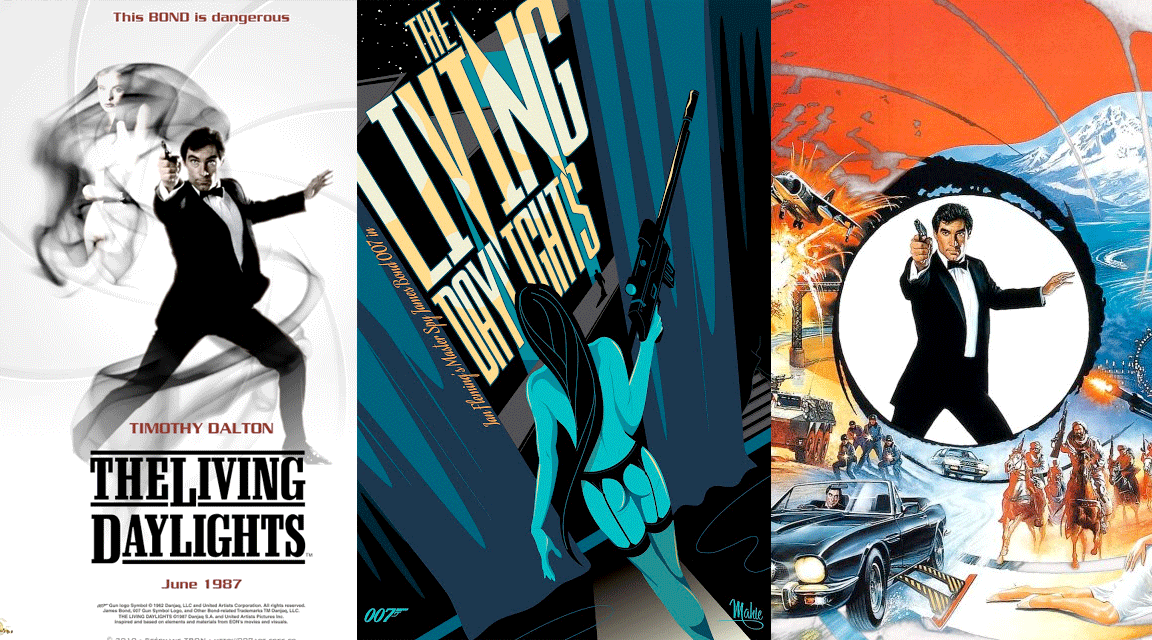

All roads lead to James Bond

In Ian Fleming’s novel From Russia with Love, the Soviet counter-intelligence organization known as SMERSH recruits a young cipher clerk, Corporal Tatiana Romanova, to defect from her post and seduce James Bond in order to set him up for assassination and humiliate Britain with reports of 007’s affair with a Russian agent. The cipher clerk’s official conscription occurs when Rosa Klebb (“The Head of Otydel II, the department of SMERSH in charge of Operations and Executions”) orders Tatiana to her apartment. Once there she interrogates the clerk with intrusive, sexually-explicit questions before excusing herself only to reappear moments later in a “semi-transparent nightgown in orange crepe de chine.”

Though Fleming reserved plenty of disgust for his grotesque creation of Rosa Klebb and the recruitment of the gentle flower Tatiana Romanova, he stopped far short of implying anything as dehumanizing Dominika’s training. Fleming wasn’t pulling strictly from his own wellspring of lecherous imagination; (his lesbian derision notwithstanding) the fictional SMERSH organization embellished characteristics from the real-life Russian Red Army counter-intelligence department. He fictionalized well-known stories of female spies sent to seduce and cohabitate under orders of their government. Their bodies belonged to the state, a method of operation that Red Sparrow hammers home relentlessly.

Sparrow inverts our perspective in From Russia With Love (1963). Instead of the dashing Western, morally superior James Bond, we identify with the film’s Tatiana Romanova. A female agent forced against her will to degrade herself in the name of her country. James Bond, of course, woos and turns Romanova’s loyalties as a result of his cro-magnon sex appeal. There’s no great impetus for Grand Guignol revenge because she’s only been made extremely uncomfortable by unwanted sapphic advances and forced to have sex with James Bond – which according to our coached Western perspective turned out to be pretty okay. The reality, of course, is far from Fleming’s fairy tale.

Corruption and rebirth

Dominika Egorova, Matsu, and Tatiana Romanova have all been exploited. These stories detail degradation of the human spirit and the prioritization of the expendable flesh. The truth of this exploitation, i.e. the events contributing to the dehumanization, should repel viewers vis-à-vis the humiliation suffered at the hands of her instructors/captors.

Dominika, like Matsu, must first survive the transformative horrors that corrupt her virginity (symbolic and/or literal) and re-render her a cold-blooded killer that uses her sexuality for power and leverage against her enemies. Her training is meant to disconnect the human from their body, to seduce and destroy without reservation, to interpret the desires of the target and offer them as means to emotional and physical domination.

This is where I feel that Red Sparrow becomes potentially more than its critics suggest. Not easily stomachned, the training scenes in Red Sparrow do not reach the levels achieved in Female Prisoner 701. Lawrence has made them cold and clinical and negated the titillation factor associated with on-screen Hollywood nudity. To its credit, the film provides some gender counterbalance. Male students are also humiliated, forced to strip and display their bodies for the class and thereby the viewers.

These scenes make up the film’s statement regarding the sexual power struggle. After a fellow student attempts to rape an unsuspecting Dominika from behind in the shower, she rips the handle from the shower and beats him, leaving gashes across his face. In class, that battered student is presented to the class, and the instructor (played Charlotte Rampling, in a tactical and knowing bit of casting) tells Dominika to “give him what he wants.”

The exercise intends to further break Dominika’s rebellious spirit, to humiliate and degrade. Instead, she undermines the exercise by undressing completely and presenting herself on the table in front of him. The would-be rapist suddenly falls victim to impotence. When Dominika removes his leverage, she castrates his power over her. Her instructors, of course, find fault in her manipulation, yet she is mysteriously given a a field assignment: to seduce an American agent (Joel Edgerton) working in Istanbul who could reveal the name of name of his Russian contact. We will not know how or why she “passed” her training until much later.

I’d like to direct you to a recent article by Elena Lazic in the Guardian that does a better job of putting this scene into contemporary context by way of discussing rape as a narrative device. She discusses how Red Sparrow both succeeds and fails at adequately portraying the trauma of the rape victim. Still, it spurred the conversation — and within the conversation itself lies value.

The Red Sparrow Atomic Blonde problem

Red Sparrow should be seen – love it or hate it – because it’s an albatross, a Hollywood film that cast major stars (Jennifer Lawrence, Joel Edgerton, Jeremy Irons), found major studio backing, and breached the exploitation genre at your local multiplex. I’m quite sure the film will continue to inspire both awe and ire among critics and viewers. That Red Sparrow draws from so many different sources of inspiration should eventually lead to at least a re-evaluation of the film among genre fans.

This is not the world Atomic Blonde, the film I believe most viewers anticipated when buying a ticket for Red Sparrow. Lacking a 1980’s gloss, familiar chart-toppers or a cathartic release in the trappings of action cinema, Lawrence’s film relies on low-lying suspense (and a subtle but effective score from James Newton Howard) – how is Dominika manipulating these men to extricate herself from this unwanted life? Likewise, the ending relies on a slight bit of misdirection, but one I found quite satisfying in light of the torture and degradation she suffers along the way. Where Atomic Blonde is a mildly amusing pop-culture pastiche, Red Sparrow digs deeper into genre and unsettling imagery that plays like a minor-key Female Prisoner 701 and forces us to consider the more unsavory baggage that goes along with the male gaze in cinema.

And what of Francis Lawrence’s ultimate success in handling the material? The opening ballet sequence teased hints of Kubrick – prolonged dolly shots, slow camera movement, long takes. Having just recently watched A Clockwork Orange again for the Cinema Shame podcast, I couldn’t help but note similarities between the way the films were shot, but also the handling of rape, sexual perversion and violence against women.

Critically wayward

It’s no profundity to suggest that Kubrick handled it with far more nuance, but Lawrence offers a measure of competency. Though not a full recommendation, I’ll call them accolades with reservation. Despite the graphic nature of the film, it still relies on an espionage framework most associated with a John le Carré spy film – plodding realism, miles of subtext, and conversational narrative advancement – and this is where Lawrence succeeds. This pacing will automatically turn away a broader audience. The director succeeds at building tension while withholding precise character motivations. We can never truly believe Dominika’s commitment to an individual state because her only true allegiance lies with her ailing mother.

So who’s left that’s willing to meet this movie on its own terms? It’s no surprise to me that Red Sparrow’s well on its way to becoming a box office dud. Critics, social media, expectations of another Atomic Blonde, Jennifer Lawrence (who’s quite good, by the way) all discouraged the film’s potential audience. The controversial and cold nature of the sexuality on display. Gaping wounds? Bone screws? Jennifer Lawrence spewing nonsense in the press about her boobs, pouring lighter fuel over the incendiary reviews and undermining the strongest elements of the film? More dissuaded viewers.

This is a patient and occasionally plodding espionage film with controversial exploitation elements that, while imperfect, do add something to the cinematic conversation of violence against women. But this is not mainstream cinema, no matter the flash or pedigree. This is a movie that presents itself as an outsider commenting on and referencing the genre from within. Red Sparrow does not court complacency; it wants to rattle cages. The violent reactions for and against the film show that it was at least successful in that regard. It deserves an audience because it is worth the conversation, no matter your ultimate perspective. Without this conversation, the next generation of Shunya Itōs may never find that balance of exploitation, artistry and nuance. Red Sparrow didn’t quite get there – but in the meantime I’ll celebrate its efforts and try to help it find the receptive, but critical audience it deserves.