First, the necessary introduction, for old time’s sake.. This ditty about Spectre marks the 24th essay in a 23-part series about the James Bond cinemas. I encourage everyone to comment and join in the conversation.

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #24: Spectre and Blofeld, the Villain Bond Can’t Quit

by James David Patrick

The title of this essay came before the essay itself. And of course it was a scene from Brokeback Mountain that initially inspired it. Jack Twist turns to Ennis Del Mar and tells him, “I wish I knew how to quit you.” Recreate that scene with James Bond and Ernst Stavro Blofeld. Let me help.

The Resurrection of Blofeld

In November of 2013, Eon Productions agreed to terms with the estate of Kevin McClory for the rights to SPECTRE and Blofeld, paving the way for the shadow organization’s return to the James Bond cinematic landscape. At the time I worried that no matter how much producers updated the Blofeld character for the Craig era, a new Blofeld would still be same old disappointing Blofeld and Bond’s greatest adversary would remain one of his weakest.

I wrote then: “It would not be impossible for QUANTUM to turn out to be SPECTRE with Blofeld at the helm, but this twist would be disingenuous, a forced bit of narrative that would only pander to nostalgic fans.” My point being that in order for Blofeld to work in 2015, in a grounded, more realistic approach to James Bond, Blofeld could not be the Blofeld(s) of previous cinematic incarnations. The character would have to be more than just nostalgia, more than just a bald head or a facial laceration. He’d have to be a brand new creation. After Mike Myers skewered the character in the form of Dr. Evil, Donald Pleasance’s Blofeld, the most iconic Blofeld, had no place in contemporary Bond. Despite dozens of other parodies and clones, Dr. Evil had finally, officially, without reservation, put that character out to pasture. Or so I would have thought.

Outside the shadowy, obscured figurehead in From Russia with Love and Thunderball, Blofeld has always boasted Gumby-like tendencies, molded to fit the whims of the individual narrative. He’s never been the true manifestation of nihilistic evil as written in the Fleming texts. Consider the Blofeld from Fleming’s unfairly maligned You Only Live Twice. Tiger Tanaka calls him “a devil who has taken human form.” In the book Ian Fleming & James Bond: The Cultural Politics of 007, Edward Comentale, Stephen Watt, and Skip Willman compare Blofeld to an amalgam of Hitler, Nero and Caligula. Like James Bond, we’re forced to reconcile that there’s both a Book Blofeld and a Movie Blofeld… and another Movie Blofeld… and another Movie Blofeld… none of which approach Nero, Caligula, Hitler, or “a devil in human form” in the annals of malfeasance. (You might find him in the neighborhood of Codpiece.)

Tiger Tanaka’s description recalls Sherlock Holmes’ description of Professor James Moriarty, Holmes’ archenemy, in The Final Solution: “But the man had hereditary tendencies of the most diabolical kind. A criminal strain ran in his blood, which, instead of being modified, was increased and rendered infinitely more dangerous by his extraordinary mental powers.” Like Blofeld, Moriarty serves as an evil incarnate; they’re not so much individual personalities as they represent an amalgam of the world’s evil. In fact, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle offered even less detail than Fleming in describing Sherlock’s greatest antagonist and intellectual rival. Moriarty made only one appearance and was meant to be a device to kill Sherlock Holmes when Doyle had come to loathe writing Holmes stories. (Of course, violent fan reaction caused Doyle to relent and bring Holmes back for an encore – explaining that his famous super sleuth had merely faked his death.) Despite a brief literary career, Moriarty has gained greater notoriety in subsequent adaptations for film and television.

Fond memories of Movie Blofeld are, in fact, not acute nostalgia. He is not the Aston Martin DB5. Fans aren’t waxing nostalgic for Blofeld; they’re waxing nostalgic for an era and non-specific warm fuzzies. They’re longing to recapture the magic of those original Bond movies starring Sean Connery. Title credits by Maurice Binder. Score by John Barry.

Blofeld’s an elusive target having been played by three actors (four including Christoph Waltz and five including Anthony Dawson in From Russia with Love and Thunderball). One person’s ideal Blofeld is another’s fop. I’d rank You Only Live Twice’s Blofeld near the bottom of all Bond villains, but Donald Pleasance’s portrayal remains the enduring image. Oft-parodied, kitschy and unfortunately iconic. Other than being sensitive about the shape of his earlobes, how could one specifically reference Telly Savalas’ Blofeld? Charles Grey’s Blofeld has become most defined by cross-dressing and effeminate cigarette holding. None of these things can be used in the grim and grounded Craig era, so far removed from these representations in time and mind. All of these cinematic appearances of Ernst Stavro Blofeld have failed to convey unlimited evil – with the exception of the Blofeld that only partially appeared on screen.

Movie Blofeld, This Is Your Life

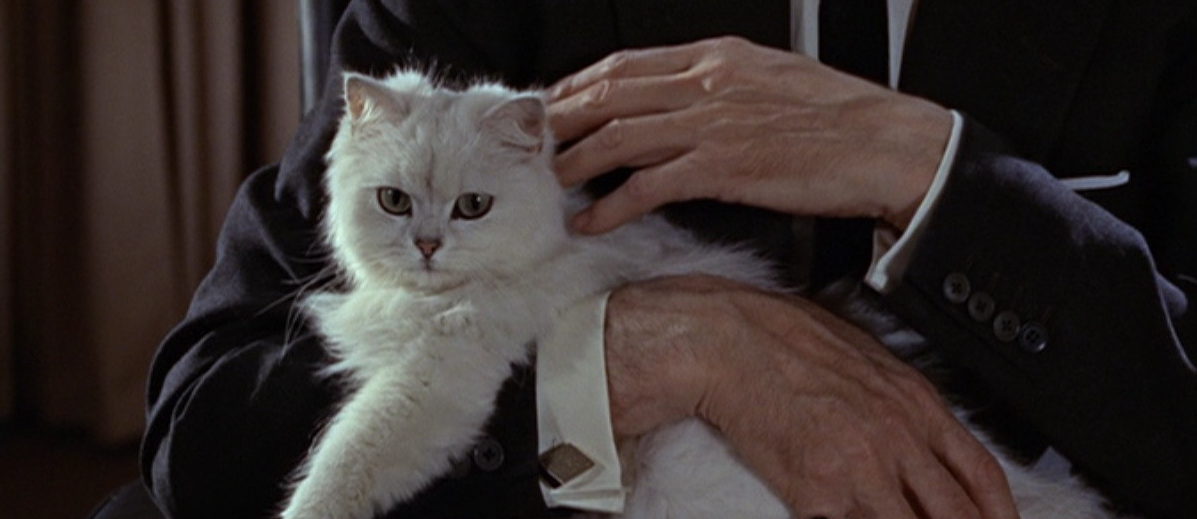

Blofeld began his cinematic career as a shadowed figure stroking a white cat. Arguably the most feared incarnation of the character was the one that never fully appeared on screen. The only way to convey the unspeakable evil as intended in Fleming’s text was to tease our imaginations. Only a hand and the terrible deeds done at his command.

In a visual medium, the most effective evil is often masked or rendered in our imaginations. Darth Vader. Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers. It’s no coincidence that the villains in slasher films almost always wear a mask. I’m reminded too of the Edgar Allan Poe story, perhaps the ultimate example of proto-slasher literature, “The Masque of the Red Death” where a masked figure wearing a blood-spattered robe walks among revelers. The guests eventually unmask the man, finding nothing underneath – thus unleashing the Red Death upon all partygoers. The story ends with the line: “And Darkness and Decay and the Red Death held illimitable dominion over all.” I’m not suggesting that Blofeld needs to be a plague-like apparition; I merely want to convey the wisdom contained within the phrase “illimitable dominion” when constructing a villain that is meant to represent all of the evil of which men are capable.

An exquisite ‘Masque of the Red Death’ illustration done by David G. Forés for an Edgar Allan Poe anthology.

In the Harry Potter universe, J.K. Rowling resisted describing a fully embodied version of Voldemort until her fourth book and this approach carried over into the faithful cinematic adaptations. And it could again be argued that the shapeless, faceless evil of Voldemort was easily the most frightening incarnation of the character. The power of imagination conjures fear out of unlimited possibility.

Think about how we experience a film like Jaws or Alien. The Xenomorph in Alien appears on screen for only four minutes, yet Alien is regularly cited as a pinnacle of horror and suspense films. The shark eclipses the Xenomorph with nearly eight minutes. These same cinematic principles apply to 007 – even though the ultimate goal of a James Bond film is not necessarily sweaty-palmed suspense.

In his essay “Theater and Cinema,” French film theorist André Bazin states that cinema is the special relationship between on-screen and off-screen space. Unlike other mediums, the off-screen space is always available to the viewer even when it is not shown. The viewer is aware that the potential for camera movement or character action taking them into the frame is always present. That which is not shown is a calculated visual effect. The most intense moments in Steven Spielberg’s Jaws or Ridley Scott’s Alien, take place when the shark or Xenomorph isn’t on screen at all. The most intense moments take place when we, the viewer, anticipate the creature because we know through aural and visual cues that they are just off-screen. The arrival of the shark or a xenomorph is actually a catharsis, a release of tension.

Blofeld’s not stalking James Bond from within an air duct, but the same principles apply. Blofeld, who makes his first fragmented appearance in From Russia with Love, is anticipated, just off screen, a perfectly evil incarnate conceived in our brains to reflect individual fears about evildoers in a post-Cold War climate. The tension of not seeing Blofeld allows our mind to furnish the image just outside the frame. The primary villain of both From Russia with Love and Thunderball was left almost wholly to the viewer’s imagination. To add to the mystery, instead of Anthony Dawson, the credits of From Russia with Love listed “Ernst Blofeld” as “?”. It’s not that we imagined Freddy Kreuger’s gnarled face on the other end of Blofeld’s arm; it’s merely the empty canvas allowing for unlimited potential. The what wasn’t so much as important as the why. Why was he such a mystery?

The appearance of the character in You Only Live Twice was inevitable; Blofeld could never have remained a mystery in perpetuity. YOLT‘s Blofeld castrated our imagination and consequently the character’s unspeakable evil. The character was stillborn, a self-parody of megalomania long before Mike Myers regurgitated this character as Dr. Evil in the Austin Powers films. Pleasancefeld said things that certainly sounded evil, but could any of us take this character seriously? Blofeld and You Only Live Twice polarized critics in 1967 just as it polarizes fans today. It should be noted, however, that fans of the film would likely not praise the efficacy of this Blofeld as a deviant criminal mastermind.

So what is it about Blofeld?

In the film that followed You Only Live Twice, Blofeld found some footing as a more grounded Bond villain in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (as played by Telly Savalas) but became a smug, cross-dressing, face-shifting milquetoast in Diamonds Are Forever, the character’s final official appearance. Charles Gray’s depiction emphasizes frivolous mania, but his cigarette holder and effete malice hardly registers as much beyond a sociopathic patron of local musical theatre. His henchmen, Wint and Kidd, eclipse him in the evil department despite an ill-conceived slapstick finale featuring flaming kebobs.

And then SPECTRE disappeared from the world of 007 when the courts awarded the rights to Blofeld and SPECTRE to Kevin McClory. Kevin McClory would go on to make his own Bond film, Never Say Never Again (with Max Von Sydow in the role of Blofeld). Bond, of course, persevered and even thrived without SPECTRE. The arrival of Roger Moore offered the Bond franchise a fresh start and a clean slate of villains. Contemporary reviews of Live and Let Die weren’t pining for a return of Blofeld or SPECTRE; they focused on how the loss of Sean Connery (again) would damage the longevity of the franchise.

Cubby Broccoli landed one final knockout punch when he made a mockery of the Blofeld character in the pre-title sequence to For Your Eyes Only by dropping him, ingloriously, down a smokestack to his certain demise. The unnamed, bald, wheelchair-bound, cat-stroking villain could be none other than Blofeld, but for legal reasons, of course, it definitely wasn’t. And this, in my opinion, was where Blofeld should have remained. Mocked. Dispatched. An outdated relic left to rot in a post-industrial graveyard.

But in this age of reboot, remake and retread, nothing once successful stays dead (or smokestacked) forever. And so Blofeld returned for 2015. I’ve been vocal in my opposition to the resurrection of SPECTRE and Blofeld not because it couldn’t be done, but because Bond needed to move on. In fact, Bond had moved on in the form of QUANTUM – the SPECTRE surrogate introduced in Casino Royale (2006).

Audiences seemed to agree that QUANTUM more than adequately resuscitated Bond’s shadow-organization adversary as depicted in Fleming’s novel of the same name. It’s likely no coincidence that Skyfall, as the third film in the Craig-era Bond “reboot,” strayed from QUANTUM just as Goldfinger had done 48 years before. (Most believe the deviation in Goldfinger was a calculated decision to avoid villain fatigue.) Then news emerged that EON had re-acquired the rights to Blofeld and SPECTRE. Suddenly I felt the presence of that creeping Xenomorph, a Xenomorph known as nostalgia, waiting just off-screen, breathing down my neck, ready to impregnate us all with moldy emotions that would emerge from our chest cavities in November 2015 to desiccate multiplexes everywhere.

Fans don’t want change; they want the illusion of change – a phrase often attributed to Marvel patriarch Stan Lee – proves relevant regarding James Bond’s attachment to Blofeld nostalgia as well. Nostalgia often replaces creative ingenuity by becoming the illusion of creativity. Recall Die Another Day’s punchless parade of homage and reference. The sudden, inexplicable appearance of the Aston Martin in Skyfall. Occasionally swells of nostalgia pay off, a wink and a nod seamlessly built into the narrative, but more often than not subsequent viewings reveal their true value to filmmakers – misdirection. In this case, Bond producers shoehorned Blofeld into the 21st century to appease fans nostalgic for Sean Connery’s Bond adventures.

Successfully weaving Blofeld and SPECTRE into a new Bond film while updating the character for modern audiences would require some of that actual, aforementioned creative ingenuity. The big question on everyone’s mind prior to the release of Spectre was how would this bald baddie be updated and woven into the QUANTUM/Craig era.

The James Bond Franchise is a Little Bit Like Kirby

Congratulations to the video gamers who remember Kirby. Yes, that old school NES character that inhaled and swallowed adversaries, thereby assuming their powers in order to complete certain tasks. James Bond is a great originator – but he is also the greatest of appropriators, borrowing liberally from popular entertainment in order to continually reinvent the brand of James Bond. The series has traded on successful genres like martial arts, Blaxploitation and science fiction, cribbed shaky-cam cinematography and gritty realism from the Bourne films and over-the-top spectacle from 90’s action flicks like XxX. Sometimes these appropriations pay off. Sometimes they lead the series astray.

Congratulations to the video gamers who remember Kirby. Yes, that old school NES character that inhaled and swallowed adversaries, thereby assuming their powers in order to complete certain tasks. James Bond is a great originator – but he is also the greatest of appropriators, borrowing liberally from popular entertainment in order to continually reinvent the brand of James Bond. The series has traded on successful genres like martial arts, Blaxploitation and science fiction, cribbed shaky-cam cinematography and gritty realism from the Bourne films and over-the-top spectacle from 90’s action flicks like XxX. Sometimes these appropriations pay off. Sometimes they lead the series astray.

Spectre, billed by producers as a return to an old-fashioned Bond, also surveyed the cinematic landscape and came away with a slightly modified agenda. Since 2008, Marvel has dominated multiplexes with its ever-expanding universe of Avengers films. Bond boasts deep ties to the comic book world, and I’ve already highlighted the Batman parallels on multiple occasions. On this occasion, however, Eon took a look at the dollars being made by widespread brand connectivity and allowed that to influence how they reintroduced Blofeld to modern Bond audiences.

It’s overreaching to suggest that Bond producers saw The Avengers and thought, “Eureka! Everything must be connected. Everything must mean something.” But I do believe that some of that wisdom seeped into the collective conscience of the Bond production team. Just as Marvel has reached unprecedented levels of selective interconnectivity between TV and movie franchises, the Bond franchise reached into its bag of tricks to retcon (short for “retroactive continuity”) Blofeld into the first three Craig-era films almost as if he’d been operating in his own parallel film franchise, playing puppet master over everything that had happened in Bond’s career to date.

This is poorly conceived shorthand meant to create the illusion of Blofeld’s omnipresence and establish the character’s supposedly unspeakable evil. But there’s the rub. Blofeld’s only evil is spoken and rarely shown. Blofeld reveals their familiar connection. Ersatz brothers. Blofeld describes the root of his mania. That Bond, the adopted son, had usurped daddy’s attentions. He then claims responsibility for the death of Vesper, the death of M, the water crisis in Bolivia. Everything that had happened to the Craig-era Bond was “orchestrated” by Christoph Waltz’ Blofeld. My response echoes Luke’s response to Darth Vader when Vader tells him about midichlorians in the following Robot Chicken clip.

Not only had Blofeld literally just spoken all this supposedly unspeakable evil (irony!), he’d turned limitless megalomania into a localized, sibling squabble over daddy’s affections. This was the creatively engineered character update for 2015. This was a massive disappointment.

Localizing the tension between Bond and Blofeld in a kind of “kitchen table politics” becomes problematic in the greater context of the Bond universe. It’s a confounding intersection Ian Fleming’s prose and cinematic emancipations dating back to Fleming’s original creation of SMERSH in Casino Royale. Fleming’s SMERSH (an acronym for the Russian phrase meaning “death to spies”) was a Soviet counterintelligence agency that became rogue in the wake of World War II. SMERSH was based on the real life Soviet counter-intelligence umbrella agency created to subvert Nazi influence during the war. For the films, Bond’s nemesis became the fictional creation SPECTRE to make the agency wholly apolitical and devoid of specific state-influenced agendas, in other words: autonomous, unpredictable evildoing. Though two films (From Russia with Love and The Living Daylights) mention SMERSH, the organization remains cinematically inconsequential.

In the Fleming novels, Bond and SMERSH engage in a tête-à-tête in the wake of Vesper’s suicide in Casino Royale. Le Chiffe also carved a Sha, the initial Cyrillic letter of “Špion,” onto the back of Bond’s hand (the scar would remain through subsequent stories). Bond swears vengeance against the organization. SMERSH does likewise. This grudge appears to be the source by which Spectre drew some of its inspiration for this Bond and Blofeld personal backstory and lingering grudge. Keep in mind, however, that Blofeld and SPECTRE didn’t appear in Fleming’s prose until Thunderball (1961). I’m withholding On Her Majesty’s Secret Service from this conversation because the aftermath of Tracy Bond’s death inspires Bond’s revenge in Fleming’s You Only Live Twice. I’d argue the SPECTRE of Fleming’s prose had no interest in prolonged personal vendettas. Bond disrupted business; business must resume as usual, and anyone who stands in the way of business must be terminated.

Fleming created SPECTRE as a purely commercial enterprise with ties to the Gestapo, SMERSH, the Italian mafia and the Unione Corse, among others. Blofeld was a businessman. Blofeld had no designs on anything but accumulating wealth and power – he was not motivated by jealousy or revenge. In Fleming, it was SMERSH, not SPECTRE, which orchestrated Vesper’s death – a key element to Blofeld’s master plan to torment Bond in Spectre. Whether you consider this narrative overreach or whether Spectre succeeded in establishing a familial rivalry is a subjective observation, so perhaps the more relevant question is why Eon felt the need to insert Blofeld into Bond’s childhood in the first place.

The Fallacy of Architecting Little Jimmy Bond’s Pain

Let’s just jump right into a James Bond, Jr.-like prequel series with Little Oberhauser gnashing his teeth and watching from the shadows of the monkey bars as James Bond pulls all the middle school honeys. Like spending more time with James Bond, Jr., further scrutiny of Bond’s limited backstory is wasted energy. Skyfall performed a requisite amount of probing. Judi Dench’s M performed her job as his surrogate mother. Bond, the orphan, has completed a satisfying familial-related narrative arc.

The adolescent (and somehow also over-the-hill) agent, reared and supported by M (and Britain, as an extension of M’s role as head of MI-6) comes of age at the end of Skyfall. Bond stares out over London, his domain. The boy has become man in the wake of M’s death, and thus the story of Bond’s youth has now been told, allowing him to assume his established position as a protector of Britain.

Returning to the emotional well of childhood immediately after this assumption of adulthood undermines the journey from Casino Royale to Skyfall. At a certain point after Quantum of Solace and after the fulfillment of Bond’s revenge fantasy, 007 needed to toe the company line, else risk permanent Craig-era adolescence.

In all four of Daniel Craig’s Bond movies, James Bond has gone rogue/off the grid/loose cannon. If Craig’s Bond cannot escape his childhood, he can never truly become James Bond. He’s more Jason Bourne, ceaselessly investigating the past he has forgotten, searching for connectivity. Jason Bourne isn’t protecting the United States; he’s engaged in a struggle with his former employer to find personal freedom. By fixating on his own past – whether it be the death of Vesper or his surrogate family, Bond has become a petulant superhero whose childhood traumas have driven him to a profession of crime fighting. Rather than a heroic protector, Bond had become a national liability.

The James Bond of the 1960’s, the James Bond over which millions of fans wax nostalgic, is a government cog, a sociopathic employee deployed to carry out Britain’s dirtiest work. That he eschews permanent relations and reflection in favor of thrills and women and unhealthy substance abuse is in itself a not-so-subtle indication of the past he’s avoiding. Critics over the years have likened James Bond to a blank slate in a bespoke suit. While that is true, it’s also proof that, perhaps, they’ve missed the point. James Bond’s persistent avoidance of self-evaluation is in itself a defining characteristic. Self-preservation in the face of psychologically damaging horrors. An unflappable external appearance to mask the battered soul within. Fleeting moments of personal reflection, like laying flowers on the grave on his dead wife in For Your Eyes Only, therefore, become far more interesting within this context of character.

By inserting Blofeld into James Bond’s past and digging up all these childhood issues, Spectre has torn at the fabric of its hero and its villain in order to render each as flesh and blood. Like Jason Bourne. Like Batman. Like the John le Carré spy universe. This act of humanizing has undermined the Manichean notion of good vs. evil that had constructed all traditional James Bond narratives (arguably until Skyfall, which more successfully gives its villain depth of motivation and shows M’s maternal figure to be fallible). By making this a personal vendetta between Blofeld and Bond, the film complicates the idea of ultimate good vs. ultimate evil. Blofeld has retaliated with greater force. Now in order to deflect blame he’s pointing at Bond and saying, “But he hit me first.”

After 300 minutes of aborted glances and conversation spoken only in subtext, Tom Hiddleston finally earns a parting glance at Elizabeth Debicki’s posterior in the 2016 adaptation of John le Carre’s The Night Manager.

Consider the Holmes/Moriarty relationship as it has played out in subsequent Holmes adaptations. Moriarty does evil to best Holmes. Holmes tries to stop him. It’s hardly more complicated than that. This dynamic resembled that of Bond and Blofeld in the 1960’s. Rendering the conflict local adds false premeditation and moral shades of gray without due development. The thing about adaptations of John le Carré spy novels is that they’re really long, like mini-series long, or interminable movie long – see The Night Manager (2016, 348 minutes) or Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (1979, 315 minutes). But they’re long because the author has taken great care to establish villains with substantive motivation and heroes with moral hiccups. These

As a result of the 21st century production model, Bond producers Barbara Broccoli and Michael G. Wilson apparently did not believe that patience in establishing a new Blofeld was a virtue. They wanted the moral complexity but not the mini-series length, or more appropriately a two- to three-movie narrative arc. Would movie audiences have stuck around if Christoph Waltz, announced as a villain in the movie Spectre, had just turned out to be #2 and not Blofeld as most everyone had anticipated? A two-film cycle in 2015 would take four to six years to complete rather than two to three in the 1960’s. They willingly sacrificed a successful Blofeld model in order to satisfy audience expectation and perceived demand. Not only do I believe that they underestimated their audience, but I also believe that they squandered their only opportunity to refashion Blofeld as someone truly frightening, per the Fleming model. Instead of unmasking this unknown figure to reveal death itself, Spectre unmasked Blofeld and found a guy named Franz with elementary psychoses. This removes the “illimitable dominion” from Blofeld’s resume and rebrands the villain as a slave to a grudge. He’s no longer a global threat; he’s driven by acute emotion. This is not the more frightening Blofeld of unlimited ambition.

(And now a word from our sponsor: Bob Barker reminds you to get your Blofelds spayed and neutered.)

A Crash Course in Establishing Menace and Malice

Take, for example, the introduction of SPECTRE in the Warren Ellis and Jason Masters James Bond 007 comic series. The second story line, entitled Eidolon, opens with the execution of a careless organization underling who “exposed the work.” The executioner in question is a man with a disfigured face named Mr. Hawkwood. Menace has been established, just as Spectre established the henchman Hinx. Even the color palettes used in the two scenes appear similar. Earth tones and black shadow. But this is where the similarities end.

Eidolon maintains mystery. There’s no mention of anything other than the “business” or the “money.” And then just before Mr. Hawkwood literally rips the man’s head off, he says, “Nobody was supposed to know about Eidolon.” Now, we, the presumably Bond-educated audience read Eidolon and we’re interested. Who or what is Eidolon?

Meanwhile, at the 39:30 mark in Spectre, Blofeld makes his first appearance. Bond slips into a posh Italian estate (using the name Mickey Mouse – very incognito) with 20’ ceilings and balconies and a conference table that’s bigger than my Boston apartment. Mendes shrouds one man, clearly the figurehead, in darkness. A minion has stepped out of line and now he must be cleansed. Enter Hinx and commence bare-handed skull crushing. Immediately afterward, at 43:57, as the shrouded man turns to address James Bond his head slips into the light, revealing the face of Christoph Waltz. Spectre plays coy with Blofeld’s identity for precisely 4 minutes and 27 seconds. Unlike Eidolon, it’s not that we’re confused about the identity of this organization. We hold more information than Bond as a result of the film’s title and the visual cues. The mystery for us as Spectre’s audience is the ultimate identity of Blofeld.

Now where have I seen this before? (Also for being a secret organization there’s a whole lot of arbitrary people at this meeting.)

No one says “Blofeld” during the conversation about this organization’s evil doings, but this is a familiar milieu. As viewers well versed in Bond, we’ve seen this “board room” in Thunderball, not to mention the parody in Austin Powers. Mendes has updated the 1960’s modernism by skewing neo-classical. The familiarity of the scene, from the characters’ orientation within the frame to the cinematography itself, informs our interpretation and expectation. So much so that we’re almost disappointed when no one’s chair turns out to be electrified.

If the production team had an eye towards misdirection, this would have been a great way to divert audience expectation. Use these familiarities to convince the audience Waltz is Blofeld, then by the end of the film show the real Blofeld, nothing more than a hand and a cat and a “?” in the credits. Spectre has a “telling” problem; there’s nothing left to fuel our imaginations – from Blofeld’s introduction to the way he informs Bond of his laundry list of evil deeds.

Back to Ellis & Masters’ James Bond 007. James Bond has been tasked with protecting an MI6 agent with a blown cover. She’d been stationed in the Los Angeles Turkish Consulate as an accountant. He’s fended off Turkish assassins, off-the-books CIA agents, and mysterious hoods with UK Special Forces weapons. At the end of the second Eidolon issue, M tells Bond and Tanner “Eidolon is another word for ghost… or spectre.” This is how you build tension with a known property. Seemingly unconnected persons across three nationalities tasked with killing Bond and the blown agent suggests unlimited influence across nations and political ideologies.

The comic merely translates “Eidolon” at roughly the same time as Mendes reveals Blofeld in Spectre – approximately one third of the way through the narrative. We know one thing about this comic-based incarnation of SPECTRE – they will do anything to protect their identity. When Blofeld leans forward into the light in Spectre, he ceases to become a shadow.

The Spectre We Deserved

Spectre teased us with a thrilling opening sequence. And through the first two thirds of the film, it seemed like Daniel Craig had finally earned the right to swagger, to casual womanizing, to a standalone Bond adventure of old. But then Blofeld leans in. Blofeld usurps Bond’s swagger and newfound independence in order to drag him into backstory yet again. Audiences were denied the nostalgia they actually craved from James Bond, ironically, by the hackneyed nostalgia Bond producers attempted to serve in the form of Christoph Waltzfeld.

The old “show; don’t tell” tenant of creative writing never felt more relevant. Stated misdeeds just don’t convey evil in a visual medium. Spectre should have been the great intersection of James Bond. Ian Fleming plus classic- and Craig-era Bond. In fact many similarities existed between the way SPECTRE replaced SMERSH in From Russia with Love and the way SPECTRE aimed to replace QUANTUM, but instead of increasing the global threat, Spectre downgraded, hoping, it seemed, to trade on old-fashioned memories with new-fangled depth of meaning and connectivity.

Spectre could have been a great Bond movie. In fleeting moments it reminds us why we love James Bond. But it also serves another master, hedging bets to maintain that broader mass-market appeal. This proves maddening because we see clearly the film we wanted it to become. The opening scene in Mexico. The tease of a unique narrative messaged by an M from beyond the grave, her last will and testament played out in the form of a James Bond mission. The seduction of Monica Bellucci’s grieving widow. The hope that our foregone conclusions of Christoph Waltz being Blofeld could be subverted by a clever narrative twist. That Waltz could have been #2 and Blofeld was still waiting in the shadows, lurking, plotting to do greater evils in Bond 25. In other words, the honest, creative ingenuity that Spectre ultimately lacked. Poor decisions cloaked by nostalgia and narrative shortcuts. When Bond pulled back the cloak, he didn’t see the face of death; he saw a franchise suddenly struggling to come to terms with expectation and its broader mass appeal.

And then we’re all left wondering… could Dr. Oatman have merely cured Blofeld’s ills before he retconned himself into all of our lives?

Previous James Bond #Bond_age_ Project Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall / Spectre