This is the 23rd essay in a 23-part series about the James Bond cinemas. I encourage everyone to read the other essays, comment and join in on the conversation about not only the films themselves, but cinematic trends, political and other external influences on the series’ tone and direction.

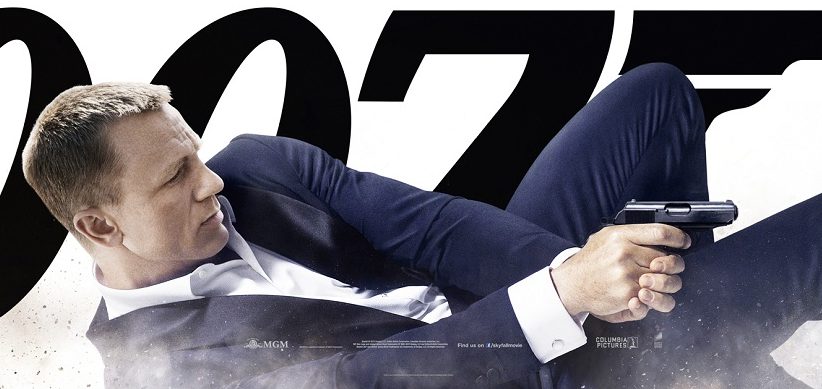

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #23: Skyfall and the Deconstruction of James Bond

Charles Darwin once said, “It’s not the strongest or the most intelligent who survive but those who can best manage change.” Malleability permits longevity. In order to survive, a species… or character must adapt.

I’ve discussed James Bond, Batman and Sherlock Holmes at some length as legendary protagonists that have endured multiple iterations over the course of generations. Born of literary roots, all would go on to experience sustained success in print, film and/or television. Bond, Batman and Sherlock share a tremendous amount of DNA but nothing more strongly perhaps than their persistent pop-culture relevance.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle blessed his Sherlock character with rich character flaws such as serial pomposity, drug addiction and a latent distrust of women. These are timeless traits that have allowed Sherlock Holmes to be a pompous but typically affable wiseass. These flaws make him human and relatable. Though he will always be the smartest man in the room, stoic and calculating, he succumbs to fear and insecurity like anyone else. Perhaps as a result, Sherlock Holmes’ feats of mental dexterity connect with broad audiences whether smugly played by Basil Rathbone or smugly played by Johnny Lee Miller.

The character of Batman, however, is built of symbols and a backstory. The Batman logo, the batsuit, the bat signal, the Batmobile. The actor playing Batman is often obscured behind costumes and custom vehicles. In Tim Burton’s Batman (1989), Michael Keaton spends 22% of the entire film (not just Bruce Wayne/Batman screentime) inside the batsuit/Batmobile/Batwing. The average for all subsequent Batman films hovers just shy of 20%. The question of character for Batman then revolves around his much rehashed origin story of childhood trauma and recovery. Bruce Wayne is Batman because he witnessed the murder of his parents. Batman longs to rid Gotham of the criminal elements that orphaned him at the age of eight.

Bond, like Batman, also boasts a collection of iconic, albeit inconsistent, suits and gadgetry at his disposal, the Aston Martin, the Walther PPK and general Q Branch gizmos. None prove nearly as identifiable as the assorted bat menagerie. Bond’s style and weaponry changes with the times… and with guaranteed promotional dollars. That EON has financed Bond independently made the franchise more reliant upon branding and promotion to pay the bills. Tomorrow Never Dies, in fact, became the first film in history to be completely financed through sponsored product placement and promotion.

What then becomes shorthand for James Bond? No one would see a Seville Row suit or a Trilby hat and identify that with James Bond as readily as one would connect the bat suit with Batman. One is merely a suit, the other a spandex/latex/armored focal point. In lieu of superficial identifiers, what connective tissues then link Sean Connery with Roger Moore and Daniel Craig? Even Sherlock’s on-again off-again deerstalker hat remains more iconic than any item of Bond attire, firearm or gadget. Bond is most identified with his theme music and regurgitated one-liners such as “Bond, James Bond” and “Shaken, not stirred” — not exactly Character or visual affectations of Character.

In an article printed on salon.com, Tom Jacobs calls James Bond “the least interesting man in the world,” suggesting that Bond owes his longevity to the “fuzziness” of character that allows filmmakers to tailor his personality to fit the tastes of an ever-changing audience. James Chapman, author of Licence to Thrill: A Cultural History of the James Bond Films says, “The only thing that Craig has in common with Connery is the character’s name.”

The concept of Bond as a blank slate has become the accepted common denominator between the various big screen incarnations of the character. James Bond resembles Bruce Wayne in more ways than one, but let’s use the notion of the “blank slate” to open the conversation. Bruce nurtures one meaningful relationship with his butler. Most see him as a vapid playboy who retires to his mansion every night to roll in piles of cash and privilege. Whether you’ve consumed every Batman iteration from Detective Comics #27 to Gotham or just Christopher Nolan’s Bond-influenced Bat trilogy, how do you describe the character of Bruce Wayne without referencing his money? Who is Bruce Wayne other than daytime Batman? Remove the batsuit. The tragic backstory remains. His parents were murdered (does he also #DERP, like Carole Bouquet in For Your Eyes Only?), thus inspiring his evolution into crimefighting vigilante. In Superman/Batman Volume 1, #3, Superman says, “Sometimes, I admit, I think of Bruce as a man in a costume.” Bruce Wayne spent his youth traveling the world and learning the various disciplines (criminology, forensics, martial arts, disguise, etc.) that would help him become a human weapon against crime. His “billionaire playboy” public persona has been manufactured to disguise his identity as Batman.

Strip away the external signifiers of James Bond. Strip away Monty Norman’s Bond theme. Strip away the opening credit sequence, the “shaken, not stirred” martini. Strip away everything that doesn’t specifically have to do with the character of James Bond. Now confiscate the tailored suit, dinner jackets, cabana wear and tuxedos. You’ve got a naked man, (potentially rather hairy) holding a small-caliber pistol, with uncertain mommy and daddy/orphan issues.

Film historian Tom McNeely cites the moment in Skyfall when Craig jumps from farm equipment to the moving train and his first order of business is adjusting his cuff. “That is James Bond,” he says. “That’s what makes him such a great fantasy hero.” McNeely suggests that the broad appeal of James Bond is based on stylish indomitability, that the appeal of James Bond is his suit, his taste in clothes, women, and the finer things in life. I want to enhance this notion one step further. It’s not just “the look,” it’s how Bond maintains “the look” and “the image” despite the vortex of violence and ugliness that follows him like the specter (SPECTRE?) of venereal disease. Conflict in Bond is that which threatens to dishevel 007’s polished veneer… and potentially undermine global order (or order as perceived by Western interests). As Bruce Wayne designed a certain path toward avenging this parents’ death – the cultivation of intelligence and physical prowess in order to reinvent himself as Batman, James Bond curated a veneer of sophistication to similarly construct a façade. Unlike Bruce Wayne/Batman, however, Bond’s true origin story – the one that ushered him toward a life of public servitude – has largely remained irrelevant.

The Orphan Issue, aka #DERP

First a definition:

DERP (dĭrp)

adj.

1. To contort one’s face into expressionlessness to express something beyond physical expression. Carole Bouquet’s DERP face conveyed loss more effectively than any actual acting could.

v.

1. A face expressing persistent dumbfoundedness as result of confusion and/or malaise. Carole Bouquet went derp de derp derp.

James Bond, like Batman, has found character development in his familial past. Bond’s backstory proves far less cataclysmic, but it does set little Jimmy Bond on a path toward national service. Not to mention the superficial indulgence in the knowledge and spectacle of refinement intended to disguise his humble origins. We’d just never been given audience with the “Bruce Wayne” beneath 007 until 2006’s Casino Royale.

Consider Vesper Lynd’s assessment of James Bond upon first meeting him on the train to Montenegro. Bond has just attempted his own reading of Vesper, to bolster the projection of himself as a diviner of human nature and therefore ace poker player. His analysis arises from a predictably hubristic place of hegemonic masculinity. (Say that five times fast.) Bond suggests that Vesper’s beauty poses a problem because she fears it prevents her from being taken seriously “which one can say of any attractive woman with half a brain.”

I reproduce Vesper’s response entirely because it’s a terrific verbal slap across Bond’s cheek, plus it prefaces the final act of Skyfall:

By the cut of your suit, you went to Oxford, or wherever. Naturally, you think human beings dress like that. But you wear it with such disdain, my guess is you didn’t come from money, and your school friends never let you forget it. Which means that you were at that school by someone else’s charity, hence that chip on your shoulder. And since your first thought about me ran to orphan, that’s what I’d say you are. [Bond tries to keep a ‘poker face’.] Oh, you are! [pause] And that makes perfect sense, since MI6 looks for maladjusted young men who give little thought to sacrificing others in order to protect Queen and country. You know, former SAS types with easy smiles and expensive watches.

Vesper’s divination of Bond’s character offers more specific character-forming backstory than we, the cinematic audience, had derived through 20 prior movies. Fleming fleshed out literary Bond’s past with more specific – if occasionally conflicting – details. (I won’t get into Fleming’s superficial inconsistencies with the character. That requires a greater study of the novels than I’ve undertaken.) In Fleming’s You Only Live Twice, it is revealed that Bond’s parents died in a climbing accident, and as an orphan Bond attended school through the charity of family friends. In terms of universal details connecting Book Bond and Movie Bond this is largely where the similarities begin and end.

Since Bond brushes aside Vesper’s accusations with a suggestive grimace, we don’t get a confirmation until that third act of Skyfall. The Bond estate serves as the stage for the climactic showdown with Silva. Bond has returned to his rural Scottish home to shelter M, off the grid, on his terms – a rather clever way, in theory (one might contest the execution), to return to a time and place representative of Bond’s film origins circa 1962. This taste of Bond’s heritage marks the first time that a movie has dared expose anything from Bond’s formative years. During my first viewing I found it thrilling, like sneaking backstage during a theater production. I couldn’t believe that Skyfall dared breach this understood divide between the audience and Bond’s past. I had presumed that we were just not supposed to know what made Bond tick. 22 movies and nothing more than insinuation and speculation. In addition to Casino Royale, Bond has faced probing questions about his past (specifically the wife issue) in The Spy Who Loved Me, Licence to Kill and The World Is Not Enough. He’s ignored or brushed each inquiry aside with wit or silence. Subsequent viewings of Skyfall have allowed me to analyze the build-up to that final scene more closely, dissipating some of that visceral entertainment brought about by smoke, mirrors and moviemaking magic and misdirection.

At Bond’s estate in Skyfall we’re given audience to the graves of Andrew Bond and Monique Delacroix Bond, Bond’s deceased parents, and the estate’s still-kicking caretaker Kincaide (played with gusto by Albert Finney). Bond’s relationship with the latter bears a resemblance to the relationship between Bruce Wayne and his butler Alfred. Consider then that Kincaide confesses to M, that after his parents’ death, James Bond found solace in the cavernous tunnel beneath the property, emerging days later a changed young man, cold and distant. Skyfall stops just shy of clubbing the audience with a batarang upside the head. (A variation upon the Bond Fever-Dream theory perhaps… Bond-Induced Fever Dreams.)

Fleming teased us with information but never delved too heavily in motivational backstory; he wasn’t especially interested in where Bond had been or who he was before his time in the service. Fleming probed the thrill and glamor of international espionage for immediate gratification, rarely exploring anything that didn’t contribute superficially to the veneer of James Bond. With Skyfall Sam Mendes dared go where Fleming never did. After 50 years of understanding the character as a “the blank slate” I had to question whether this was an unwelcome intrusion into the long-guarded (or at least purposely avoided) mystery that built the James Bond character.

Sidenote: Book Bond, This Is Your Life.

Bond is a discriminating connoisseur with more than a dash of “stodgy old Brit.” He offers thoughts (mostly criticism) on all manners of proper and acceptable behavior. Book Bond reveals that he distrusts anyone wearing a Windsor knot because it “was the mark of a cad.” Not coincidentally, SMERSH agent Donovan Grant wears a Windsor in From Russia With Love. The moment in Goldfinger when Movie Bond proclaims that the only way to listen to the Beatles is with earmuffs reflects Book Bond’s caustic sensibilities.

Vesper Lynd, in Casino Royale, opines that the agent reminds her of a colder, more ruthless Hoagy Carmichael. The Hoagy Carmichael reference appears again in Fleming’s Moonraker. I found this recurrence quite unusual as Hoagy Carmichael was not a conventional beefcake. This stems from another one of Fleming’s included autobiographical details as Fleming himself was said to resemble the American songwriter. For what it’s worth, Book Bond didn’t see the resemblance to Carmichael. He waxes solipsistic in Chapter 8 of Casino Royale:

“His grey-blue eyes looked calmly back with a hint of ironical inquiry and the short lock of black hair which would never stay in place slowly subsided to form a thick comma above his right eyebrow. With the thin, vertical scar down his right cheek, the general effect was faintly piratical. Not much of Hoagy Carmichael there, thought Bond… ”

Subsequent theorizing has suggested that Fleming crafted Bond in the image of his brother Peter and that since no one would know what Peter Fleming looked like, he came up with the Hoagy Carmichael reference. Perhaps the most vivid representation of Fleming’s image for Bond comes from a drawing he had commissioned for a comic strip in the Daily Express. To my eye, the drawing looks quite like a young Peter Cushing, but also a bit Peter Fleming.

Despite what Fleming shares with us through prose, the most precise depiction of Bond comes from SMERSH’s dossier on 007, ripped straight form the text of From Russia with Love:

First name: JAMES. Height: 183 centimeters; weight: 76 kilograms; slim build; eyes: blue; hair: black; scar down right cheek and on left shoulder; signs of plastic surgery on back of right hand (see Appendix A); all-round athlete; expert pistol shot, boxer, knife-thrower; does not use disguises. Languages: French and German. Smokes heavily (N.B.: special cigarettes with three gold bands); vices: drink, but not to excess, and women. Not thought to accept bribes.

This man is invariably armed with a .25 Beretta automatic carried in a holster under his left arm. Magazine holds eight rounds. Has been known to carry a knife strapped to his left forearm; has used steel capped shoes; knows the basic holds of judo. In general, fights with tenacity and has a high tolerance of pain (see Appendix B).

To clarify, the “plastic surgery on back of right hand” references the SMERSH symbol carved there in Casino Royale and the “high tolerance of pain” likely references the testicle mashing undertaken in the same story.

Schlep, James Schlep

Despite the extra-textual assertion of Melina Havelock (Carole Bouquet) in For Your Eyes Only, the death of one’s parents does not a whole character constitute. Bond existed for 44 years and through 5 different actors without the scent of an origin story. Does Bond really owe his longevity to chameleonic malleability dictated by the shifting socio-political and cinematic climates? Let’s think on our sins of generalization for a wee spell.

It’s become popular to question why Bond still matters. The question isn’t why Bond still matters. The question should be: Why did Bond ever matter? This is an important distinction. Over the years much has been written about Bond’s relevance or irrelevance in our fractured modern times (i.e. post-Cold War, post-espionage, post-feminist, post-AIDS). Look no further than the box office for Skyfall or the furor over the smallest casting announcement for the upcoming and 24th Bond film SPECTRE for proof that Bond remains relevant. I find the ongoing argument about modern relevance prosaic. Much like cicadas, critics and cinematic pundits emerge from their subterranean dwellings every so many years call for Bond’s permanent demise and ruffle feathers for readership.

In Louis Markos’ essay “Nobody Does it Better: Why James Bond Still Reigns Supreme” (from the compilation James Bond in the 21st Century: Why We Still Need James Bond) he compares James Bond to Clark Gable at the peak of his popularity. “[Gable] was equally idolized by his male and female fans. Men wanted to be him; women wanted to be with him.” Early in his career, Gable similarly curated a movie star as blank slate image. Gable’s acting coach, Josephine Dillon, paid to have Clark’s teeth repaired, bulked up his slender frame, taught him posture and body control. She trained him to speak in a lower register (his voice was naturally high) and pay closer attention to his facial ticks and expressions. William Clark Gable of Cadiz, Ohio was refashioned for Hollywood as Clark Gable.

This “Men wanted to be him; women wanted to be with him” adage has also found traction with Bond as well. Markos calls Gable Hollywood’s “It” man, contrasting with Clara Bow, Hollywood’s original “It” girl. Actors earn the “It” label through universal appeal to both sexes. Men desire the strength, wit, machismo and worldly sophistication of Clark Gable and James Bond just as women want to be with a man of such qualities. As long as Bond can continue to cultivate this “It” quality, he will remain perpetually relevant. This universal appeal also fostered Sean Connery’s immediate cinematic success as James Bond back in 1962.

Aside: There’s a convincing argument floating about that Movie Bond is the female fantasy figure (charming, debonair and physically impressive) and Book Bond is the unhinged male fantasy (the brooding, Byronic government lackey that beds women and kills for his employer). I make this assertion to provide an interesting counterpoint to the “men wanted to be him, women wanted to be with him” statement (that also highlights the differences between Book and Movie Bond), and that contrary to popular belief, the James Bond movie franchise has not been fueled by men, but by the “crossover” appeal for women. Now I shall ignore this notion for the sake of forward momentum.

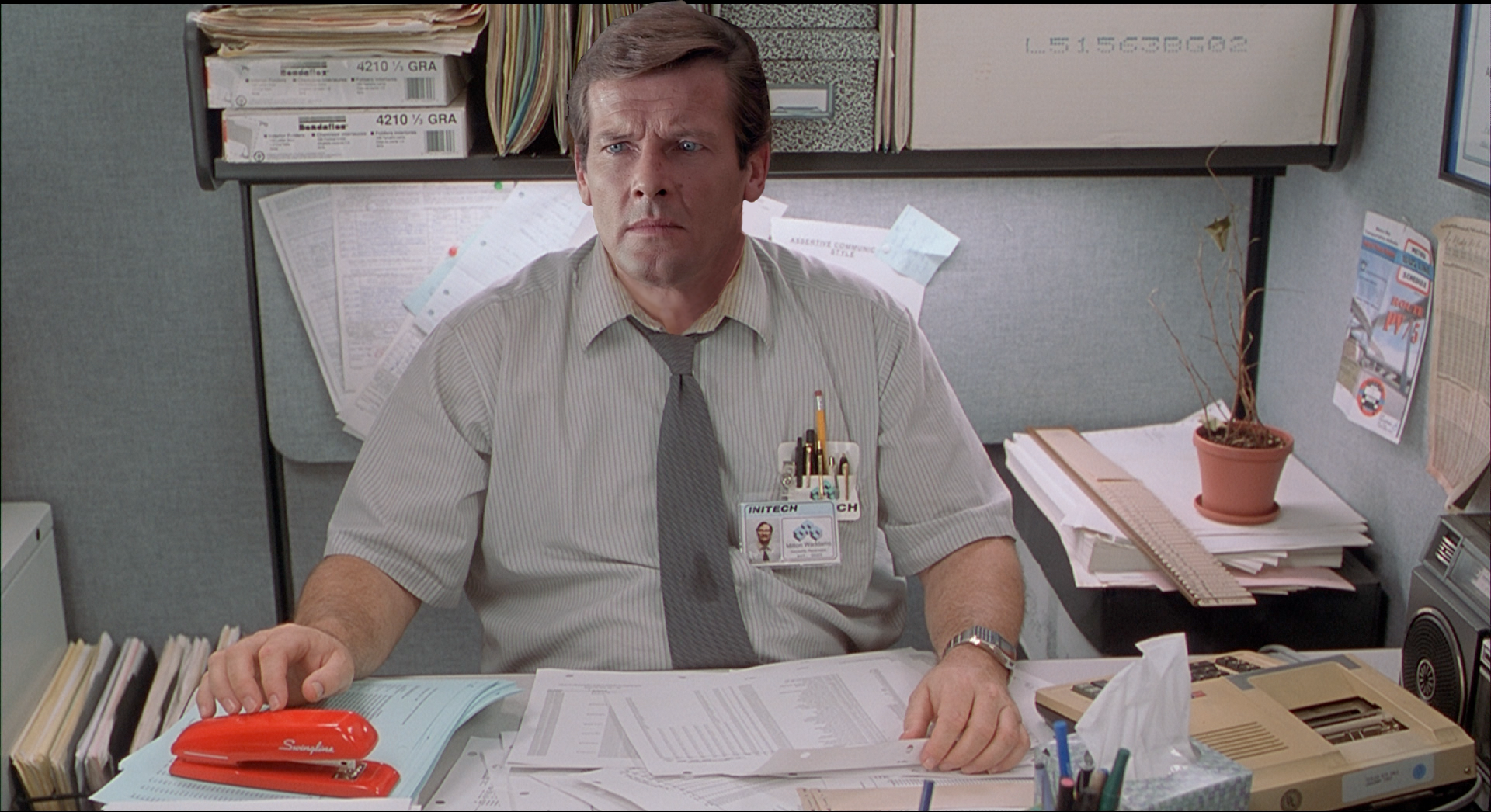

Above all else perhaps Bond’s universal appeal can be found in stability – the government employee with the steady paycheck and a presumed UK Government Service Pension waiting for him upon his retirement. Perhaps I should say he’s the pretense of stability. A polished, professional exterior, under which lies the rebellion of James Dean, the tenderness of Cary Grant, the bare knuckles and steely gaze of Charles Bronson, the wit of Groucho Marx. James Bond is the ultimate Frankenstein monster of Hollywood unisex fantasy, an impossible amalgam of charm, charisma and ability wrapped inside a man who is, at the end of the day, merely, as Markos says, “a government employee answerable to a hierarchy of bureaucrats.”

I polled Twitter, looking for some favorite workaday schleps. Jack Lemmon, as one example, made a career out of playing beleaguered schleps in films such as The Apartment, Save the Tiger and The Prisoner of Second Avenue. Woody Allen’s name came up, in just about every movie he ever made. In action movies, John McClane in Die Hard resembles the schlep (and in some ways that aforementioned male fantasy), though the weight on his shoulders derives from his labored familial relationships rather than soul-sucking employ. As long as there have been tyrannical employers there have been likable schleps, oppressed by the weight of the world. Consider, also, Danny Glover’s Murtaugh in the Lethal Weapon films, a police detective who’s “too old for this shit” and just hopes to live long enough to see retirement and the benefits of that pension.

Unlike those poor bastards, James Bond transcends the stereotype so completely that the notion of Bond being a put-upon cog in towering sea of government bureaucracy feels like an incongruous farce, the basis for a post-Weekend Update sketch on Saturday Night Live that inevitably goes on too long before mercifully ending, though still without a punchline. Consider the MI6 paper trail. James Bond answers to M (M means middle management here) who in turn answers to the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, as the representative of the British Government, answers to Parliament, and the Parliament, in theory, answers to the monarchy.

In other words, James Bond, licenced to kill… and fill out TPS reports for Queen and country.

Every time Bond engages in for a combative conversation with M, we’re keenly aware of his status. He’s unfairly maligned. He’s criticized for his professionalism and lack of responsibility despite regularly succeeding at his assigned and unseemly tasks. It is not that we, the viewer, pity Bond for bearing the weight of his oppressive responsibilities. Instead we’re attracted to Bond because of his transcendence of social class, the man‘s inability to get him down. Despite his lowly status on the totem pole, James Bond blends seamlessly with the wealthy and cultured. He always appears at ease whether he’s in the Bahamas or Monte Carlo or Thailand. He sips Bollinger champagne and samples the finest caviar without betraying the blue collar beneath his perfectly tailored tuxedo. He’s living a dream of lavish excess on the government’s dime – a full year of Bond’s salary wouldn’t cover a day in the life of 007.

The audience identifies with Bond’s status as a time-card puncher, but unlike other workaday schleps, the identification comes without self-loathing by either party. Bond has pulled off a high-wire act. He’s replaced oppression with smug narcissism and puerility, unlikable characteristics that have been rendered endearing through social masquerading and unlimited charm. It is as if James Bond is actually the carbon copy Batman. Bond puts on a mask to mingle with the world’s elite while Bruce Wayne dons the mask to “dance with the devil” and combat Gotham’s seedy underbelly. With each character, however, one could argue that they are most comfortable behind their respective facades, that Bruce Wayne prefers to be Batman, and James Bond, government schlep, prefers to be 007.

This isn’t the James Bond we’re watching in Skyfall.

Skyfall’s peek into Bond’s past challenges the barrier that allows the audience to romanticize our government schlep. Skyfall scribbled on the blank slate and ruffled Bond’s immaculately tailored suit. Skyfall ceases to be a proper Bond movie not just because we are allowed access to Bond’s early childhood demons, but because Bond finally breaks beneath the oppressive weight of his occupational bureaucracy.

Where have you gone, James Bond? (by Simon & Garfunkel)

I can’t shake the image of old James Bond sitting by himself in Dinky Donuts dunking his donut in coffee. Kramer bounding into Jerry’s apartment, spinning improbable yarns about how he saw the great, aged superspy James Bond in Dinky Donuts and oh oh oh he’s a dunker all right. He’s so focused, you see?

Previous James Bond #Bond_age_ Project Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall / Spectre