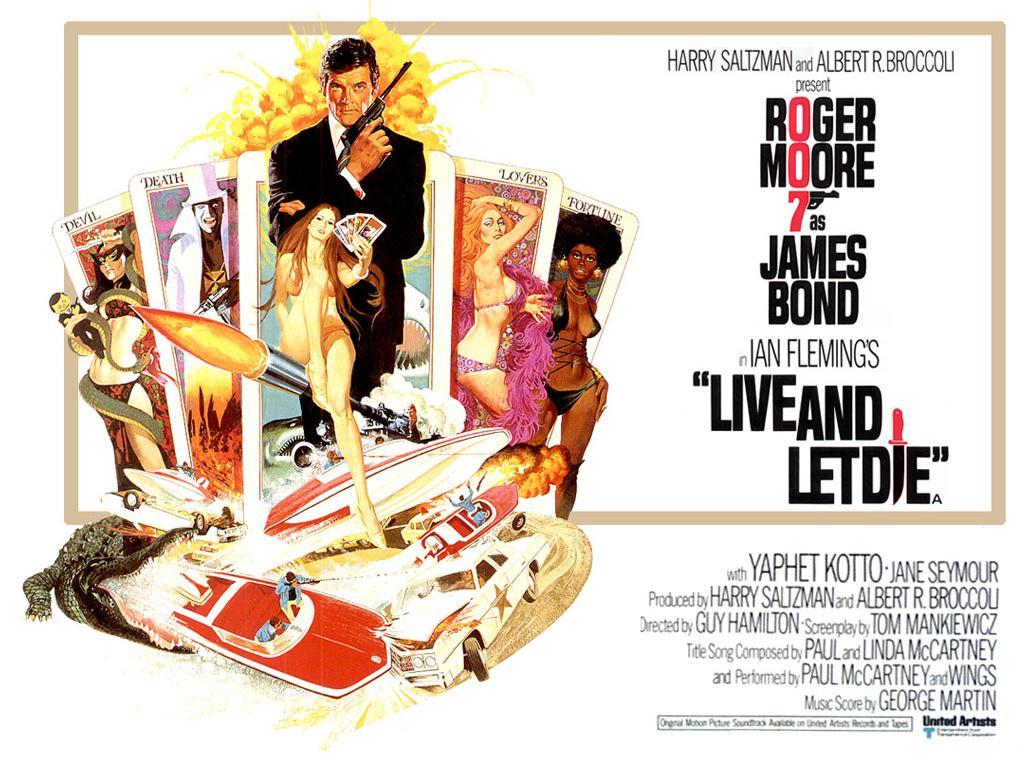

This essay on Live and Let Die is the eighth in a 24-part series about the James Bond cinemas. I encourage everyone to comment and join in on an extended conversation about not only the films themselves, but cinematic trends, political and other external influences on the series’ tone and direction.

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #8: What You Write About When You’re Writing About Live and Let Die

by James David Patrick

Live and Let Die is a powder keg. Both behind the scenes and on camera, Live and Let Die offers more controversy per minute than any other James Bond movie. This is a fact. It is incontrovertible and has been proven by very meticulous scientific research. Thus, pinpointing one talking point seems foolish. Instead, I’m going to try to make all the controversial pieces fit together in a mosaic of images and cultural artifacts in a roundabout way that somehow ends up shedding light on the movie’s two major talking points: Roger Moore taking the Walther from Sean Connery and the problematic topic of race.

I’m going to begin by highlighting one word. Panic.

EON Productions may have maintained a strong chemin de fer face, but behind the confident facade the Saltzman and Broccoli partnership had, for the first time, shown serious signs fatigue. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service had taken its toll on both producers. They’d tested their theory that they could stuff any monkey in a tuxedo and call him James Bond; the results were not what they’d hoped. Their test-primate, George Lazenby, had abandoned the post before Diamonds Are Forever and so they went back to Sean Connery, tails between their legs, hoping to repair their relationship with the actor by presenting pocketbooks agape. Connery took them to the bank. As a direct result Diamonds Are Forever suffered. Despite the unprecedented payday, Connery again reiterated that he would “never” return to the role of Bond. United Artists, in their infinite wisdom, wanted an American to play Bond. Clearly they thought domestic box office had been hurt by the “Britishness” of it all. In the past they’d tossed around the names of Burt Reynolds, Clint Eastwood, Robert Redford (clearly, United Artists could not be left to their own devices). Harry and Cubby fought desperately to ensure that Bond would be played by a British actor, but the two had also fought amongst each other about who would become 007. Indeed, some trepidation could be understood considering the entire franchise perhaps hung in the balance. Cast the wrong actor and the series might have ended right there. How long were audiences going to jump from one actor to the next without any kind of continuity? Cubby and Saltzman had to cast an actor that wanted to stick around.

When they committed to Roger Moore, they committed to a brand new direction.

In a 2012 GQ interview, David Williams asked Roger Moore about his defining moment as 007. When Roger Moore didn’t have an answer, Williams suggested the moment in The Spy Who Loved Me when Bond drives out of the sea in the Lotus and drops the fish out of the window. Moore recalled: “Cubby said, ‘can you be dropping a fish when the car is waterproof?’ I said, ‘Cubby, it’s a movie.” Williams then suggests that Connery could never have pulled off that gag. Moore responds, “I think the difference between us is that Sean is a killer and I’m a lover.”

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I don’t get to write about Moore’s best, The Spy Who Loved Me, for a couple weeks.

But Williams touches on something that I find inherently interesting about the process that led to Moore’s casting in Live and Let Die. He isn’t Sean Connery. It’s inherently obvious, but it’s an important point to consider. Roger Moore could not play a role meant for Sean Connery. So why would EON take a different tact after desperately throwing mad cash at Connery to return?

The theory I’m running with is that Cubby and Saltzman knew that Lazenby had been at least partially correct by suggesting that Bond, in his current incarnation (the incarnation created by Connery), was a dinosaur that couldn’t survive the progressive 70’s. While they believed their creation not only transcended the actor but also the decade of his cinematic birth, they still had to tap into a cultural undercurrent, a zeitgeist perhaps, to perpetuate his relevance. In 1969, Bond had become self-aware in OHMSS, but had maintained a deadly seriousness about the Bond mythology. Diamonds Are Forever found a confused middle ground, mixing black comedy with stale Bond tropes that would come off as unintentional self-parody.

The failure of OHMSS stung. It was EON’s first attempt to redesign the Bond franchise for this new era, and audiences did not respond. Instead of staying the course, the Bond producers panicked. First they returned to their bankable star. A Band-Aid to suture a gaping wound. Without Connery and now without a discernible style, Broccoli and Saltzman took a look around at the cinematic landscape. Bond was no longer a trendsetter. The industry and audience had moved on. But what had the audience moved on to?

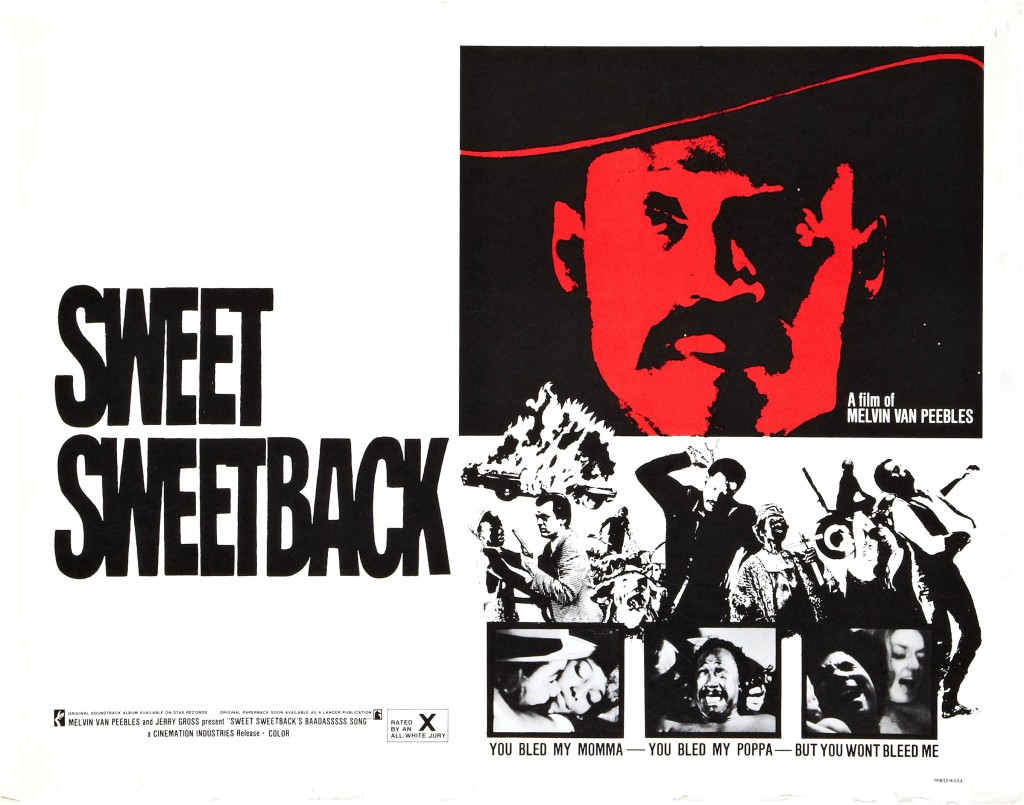

If there were one term that I would use to summarize the cinema of the 1970’s it would be “disenfranchisement.” The epic Technicolor films gave way to shades of black, small gritty dramas, grainy film stock and a rebirth of auteurism. None of this described James Bond. So Broccoli and Saltzman did what any good businessmen would have done. They began cherry-picking familiar elements from popular contemporary cinema. In 1971 (the year that Diamonds topped the box office), Shaft and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadassss Song made a more than respectable $12.1 million and $15.2 million respectively. 1972 had Shaft’s Big Score! Taking home another $10 million. The logic obviously went thusly: These low-budget blaxploitation films targeted a black audience but found broader crossover appeal. Add a budget and the name James Bond to the title and blammo! Success. And to a certain extent, Cubby and Saltzman were absolutely correct, but it all depends on your angle of approach.

Live and Let Die outperformed OHMSS but fell short of Diamonds’ Connery-inflated domestic gross. It excelled in the global market, however, despite being largely set in a dirty, dirty, oh so dirty New York City underbelly populated by criminals and hoods ripped straight from the aforementioned blaxplotation films. Jive was talked and jive was walked. And in the middle of all of it all, roamed James Bond. The result is a dated film of curious clichés, controversial stereotyping and alien (at least to the Bond series) genre tropes. The buoyed box office resulted in more genre-hopping for Bond’s next adventure The Man With the Golden Gun, which further disrupts the formula by adding martial arts, a genre made mainstream by Bruce Lee’s Enter the Dragon (which debuted the same year as Live and Let Die).

This detour into pillaging pop culture resulted into arguably sub-standard Bond movies. Each has elements of interest and can be considered acceptable entries in the “Bad Bond Movies We Love” conversation, but both are made more interesting as studies of series endurance and transition rather than individual merit. Both are notable for their villains and experiments in Bond “otherness” or as some have put, “Bond in transition.” Both Roger Moore and EON went to lengths to introduce a new direction for James Bond. Bond drinks bourbon and smokes cigars (a reflection of Moore’s personal preferences). Moore errs on the side of snark instead of snarl and beds women with charisma (smarm?) rather than Cro-Magnon sex appeal.

Despite the relative success of Live and Let Die, audiences and critics were united: Roger Moore was no Sean Connery.

There’s that kooky assertion again, but it was naturally the focal point of many of those reviews. Nobody it seemed, not the critics, not the movie-going public could agree on much of anything else regarding Live and Let Die. Here is an excerpt from a 1973 review, courtesy of Roger Greensplin of the New York Times that takes particularly harsh opinion of Moore:

There are three chases (four, if you stretch a point), including one by car and motorboat that gets so complicated it allows for character development. One actor, Clifton James, who appears only during the chase, gets fourth billing in the cast list.

The names above Mr. James’s do not seem so impressive. Roger Moore is a handsome, suave, somewhat phlegmatic James Bond—with a tendency to throw away his throwaway quips as the minor embarrassments that, alas, they usually are.

This observation should be met with some glee from #Bond_age_ live tweet regulars – we’ve turned Clifton James’ Sheriff J.W. Pepper into an ironic folk hero. Greensplin refrains, in this short and largely conflicted review, from going into much detail about the particulars of Clifton James’ role, which perhaps is for the better. The subtext here is that Roger Moore’s portrayal of James Bond is not much more useful than a one-note, chaw-chomping, redneck sheriff from backwoods Louisiana. Which is, without a doubt, a brutal comment on Moore’s interpretation of James Bond (nor does it speak well of Jane Seymour or Yaphet Kotto). I singled this review out because it was the only one I read that didn’t contain the name “Sean Connery.” Which is no small feat. It also segued into the second half of my conversation about Live and Let Die with another (perhaps) unintentionally bold statement.

Torchlight, Voodoo drums. Dark bodies writhe in the mounting frenzy of some unspeakable tropical rite. Suddenly a door is flung open and framed within it stands a beautiful white girl held captive by two monstrous black men. Her filmy white gown scarcely covering the soft contours of her body, she is dragged — protesting — to a crude scaffold and there is tied fast.

As if by signal, the ranks of jeering celebrants open and there advances an executioner, laughing, stomping, hideously costumed. He holds a poisonous snake in his outstretched hands, a snake whose bite is destined for the smooth young bosom…

Whatever the quality of this little scenario, you must admit that to stick it into a movie these days takes nerve. Merely to make a new adventure movie in which all the bad guys are black and almost all the good guys are white, and which includes in its climax the (near) sacrifice of a (recent) virgin—takes nerve.

At face value the statement “…all the bad guys are black and almost all the good guys are white” sends up red flags, sets off parked car alarms and causes otherwise bold scholars to cower. As a once (and always) self-employed scholar I don’t know if I’m any more qualified to make an assessment here, but according to rules of #Bond_age_ I’m charged with talking about these Bond movies with frankness and honesty. A conversation about Live and Let Die that avoids the topic of race is neither frank nor honest.

It would be easy to criticize Live and Let Die because of the apparent division between the (almost) all Caucasian “good guys” and the all African-American “bad guys.” Consider a few other points: Solitaire (Jane Seymour) is under the control of the black gangster Kananga (Yaphet Kotto). It is made explicit that she is a virgin and that because of her virginity she has the power to see the future through her tarot cards. Kananga has informed her that she will lose her power only when he decides (subtext: “You’re going to have sex with me when I decide.”) Bond, meanwhile, uses a stacked tarot deck to convince Solitaire that they were meant to be lovers and thus rob Kananga of his control over her. The racial dimension here is that she is a virginal white girl in need of rescuing from a black captor (that threatens sexual violence) by the white hero. Furthermore, there is the double standard that presents the miscegenation between Solitaire and Kananga as abhorrent but Bond’s encounter with Rosie Carver, a black woman, is treated as a non-event, a non-event, that is, before it is discovered that she works for Kananga and must be bumped off. In James Chapman’s Licence to Thrill, Chapman cites Richard Schickel’s review from Time to represent the critical backlash: “Why are all the blacks either stupid brutes or primitives deep into the occult and voodooism? Why is miscegenation so often used as a turn-on? Why do such questions even arise in what is supposed to be pure entertainment?”

All of this is problematic to say the least, but Live and Let Die does have one defense against all of those that would accuse it of racial bias. The black villains in Live and Let Die all seem to be far more intelligent than the white characters (who they repeatedly con and manipulate), with the exception of James Bond, of course, he who must survive to win the day and return two years later in The Man with the Golden Gun. Bond had been battling evil old white guys and Arian goons for years. It only stands to reason that he’d eventually have to face a villainous black man at some point. Other than the color of his skin, Kananga has no primary characteristics largely discernible from any other Bond villain. He boasts an elaborate scheme that is ultimately undone by James Bond, hubris, and irrational, boundless desires. Furthermore, that Bond requires help (it is an important distinction that he does not merely accept help) from two very agreeable black characters complicates accusations of cut-and-dry racism.

Taking all this into consideration, I’m of the opinion that the eighth Bond film isn’t racist so much as it is dated and misguided, that said, there are regrettable elements that provide enough fuel to sustain this argument, now, forty years after its release. Released during the decline of the blaxploitation genre, the Bond movies had ceased to be events rather than enjoyable film-going obligations. Bond had ceased to be its own genre. EON had become re-active rather than pro-active, making a genre-style of film outside their comfort zone as they searched for a new direction in the wake of the “Bondmania” Connery era. This doesn’t excuse the unfortunate creative decisions, but it does help explain how the same people that made From Russia With Love and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service could also come up with Live and Let Die. It should come as no shock, however, that the same people who created the “barn scene” in Goldfinger could also overlook some of the more troublesome subtext in Live and Let Die.

It would require another misfire (and more questions about race and stereotyping) in Man with the Golden Gun before Broccoli and Saltzman would figure out how to finally use the actor that wasn’t Sean Connery and deliver one of the best pure Bond movies in the series’ history. Thank goodness that Cubby and Saltzman never listened when all those critics in 1973 (and again in 1975) suggested that it was time to put Bond out to pasture for his alleged crimes against humanity.

And just so I feel like I’ve talked comprehensively about Live and Let Die:

Crocodile hopping, hell yes.

The Other James Bond #Bond_age_ Project Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall / Spectre

Trackbacks/Pingbacks