Casino Royale is the 21st essay in a 24-part series about the James Bond cinemas. I encourage everyone to read the other essays, comment and join in on the conversation about not only the films themselves, but cinematic trends, political and other external influences on the series’ tone and direction.

(Welcome, Snoopathonners!)

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #21: Dispatching the “Reboot” and the Derring-Do of the many Casino Royales

by James David Patrick

The term “reboot” first became buzzworthy in 2005 when Christopher Nolan begat a new Batman universe only eight years after George Clooney last donned Joel Suckmaker’s bat nipples. The word “remake” had become tarnished from frivolous overuse and poor decision-making and synonymous with the industry’s dearth of creativity, or perhaps more appropriately, trembling risk averseness. As what can only be seen as a sly marketing ploy, the term “reboot” replaced “remake.” The term, of course, wasn’t a Hollywood original. True to form, Hollywood, the great appropriator (and/or corruptor), borrowed “reboot” from the comic book industry, which had, in turn, borrowed it from the computer science industry. “Reboot” derives from the idiom to “pull oneself up by the bootstraps” – an apt description for what happens when a franchise finds itself at the bottom of a creative well.

The reboot (or “relaunch” as it was originally called in the comic industry) become a proven method to grab readers’ attention when the creative minds behind a series turned over and the new shepherds, naturally, wanted to take the character in a new direction, update the look, perhaps change the art style altogether. It’s no myth that potential readers are more apt to pick up a book numbered “1” rather than a book marked “292.” There’s always a desire to be invested in something from the beginning, to own the first issue of a potentially groundbreaking series. In a culture that devours and digests media at speeds limited only by our broadband connections, blink and you’ll miss the pop-culture rise and subsequent swan dive into irrelevance. Immediate success, rapid consumption, social media buzz… followed by the day after backlash. Appreciate for a second, even if you consumed media in a pre-Internet society, exactly how the sharing of culture took place before the opening of the digital highway. A few prominent print magazines. TV commercials. Word of mouth. Fan newsletters and propaganda via the United States Postal Service. I still have my Star Wars fan club newsletters from 1985, signed personally, I’m sure, by George Lucas himself.

It’s no coincidence then that the comic book and movie industries have begun rebooting their franchises with ever-increasing rapidity to echo the rate of consumption. Batman. The Hulk. Superman. Sony’s Spiderman franchise has become the poster child for this phenomenon. Despite the lackluster returns on the ill-received Spiderman 3, Sam Raimi’s Spiderman 4 starring Tobey Maguire remained full speed ahead… until Sam Raimi voiced concerns over the script and requested a new direction. Rather than send back the tepid corned beef sandwich, Sony opted to order pastrami instead. They were “looking for a story that just wasn’t there,” according to Sony Pictures co-chairman Amy Pascal, which sounds like an admission that it was just easier and cheaper to recycle the origin story than pay someone to fix a series fractured by one creative misstep – even a franchise as successful as Raimi’s Spiderman trilogy.

Reboot vs. Remake

The “remake” has long been a cherished Hollywood tradition.

Altogether now: How long has it been a cherished cinema tradition?

Well, I’m glad you asked. Siegmund Lubin remade (some would say ripped off) Edwin S. Porter’s landmark 1903 film The Great Train Robbery shot-by-shot seven months after it was released. Based on an 1896 story by Scott Marble and best known as the film that pioneered cross-cutting, composite editing and camera movement, The Great Train Robbery became one of the first examples of narrative cinema and the American film industry’s first commercial success. Lubin saw an opportunity for easy cash and took advantage of slow distribution chains and no regulation regarding copyright or intellectual property. Peter Decherney, in his book Hollywood’s Copyright Wars, suggests that cinematic piracy was less shady business and more a part of the public business model of the first generation of American filmmakers. With the exception of those pesky intellectual property laws, not a lot has changed over the last 111 years.

But how does one differentiate a remake from the reboot? A remake is the recycling of elements from one individual film in order to update the narrative for a modern audience (or make easy box office on a known commodity). A reboot intends to restart a franchise. Concern for the faithful retelling of an original film optional. A reboot often states an intention to re-evaluate or return to the source material. The notion of reboot has strong ties to the comic book industry in both print and cinematic adaptation. It’s the natural evolution of a character or series that has outlasted now-dated technology and aesthetic or cinematic trends.

Some filmmakers have presented the term “re-imagining” as an alternative to “remake.” A re-imagining borrows characters and perhaps some plot points but the original story has largely been dispatched in favor of something newer and shinier. Tim Burton referred to his Planet of the Apes film as a “re-imagining” and the term has been recycled occasionally since then. For our purposes, however, we’re going to ignore this entirely. The term feels like a Christmas bow stuck on re-gifted juicer.

The differences between reboot and remake become cloudier and largely semantic the more one studies individual eccentricities and overlapping concepts. Take for example Superman Returns,which picks up after the events of 1980’s Superman II (pre-Richard Pryor weirdness) or the even more confounding Star Trek (2009). Star Trek could be a reboot… if it wasn’t both a prequel and a sequel of the original Star Trek films due to the time travel/alternate reality premise.

James Bond also got swept up in the reboot craze. Released the year after Batman Begins and boasting a “fresh” take on the old double-oh, Casino Royale got slapped with the reboot label. Unfortunately, the term stuck and remains a part of the broader conversation about the Bond franchise.

It’s time we ripped it off. At least before it sits there long enough to leave that gummy residue behind. If you have a bottle of Goo Gone handy, let us begin. If no Goo Gone, we’ll have to scrape it off with our fingernails and good luck getting that out from behind your thumbnail without a good manicure.

While the argument might fall into the gray area between semantics and inconsequential puffery, Casino Royale is not a reboot. It’s also certainly not a remake, and don’t even think about trotting out that “re-imagining” nonsense. The eras of James Bond, largely determined by the actor playing Bond, prove to be something else entirely, but what they are, exactly, depends on your own perception of the series. Finding the pulse of Casino Royale will explain how it revived the franchise without actually hitting the reset button.

The Rights to Royale

Casino Royale’s journey from page to screen tells an odd and fascinating story about the nature of adaptation and rights ownership that lends some interesting backstory to the reboot/remake argument.

Ian Fleming published Casino Royale, the first James Bond novel, on April 13th, 1953. In that first run, 4,728 copies were printed by UK publisher Jonathan Cape. All sold out in less than a month. A second run was printed. And then a third. They all sold out by the end of May. Casino Royale had a harder time gaining footing in America where three publishers turned the book down before MacMillan picked it up. The book sold only 4,000 copies over the next year. For a paperback release, CR found a home with the publisher American Popular Library. Fleming suggested new titles to boost sales, but his suggestions of The Double-O Agent and The Deadly Gamble were discarded in favor of the inexplicable choice You Asked For It. American Popular Library also Americanized the name of Fleming’s protagonist to Jimmy Bond. Neither ploy succeeded. American book sales continued to drag.

In 1954, Fleming sold the rights of Casino Royale to CBS for $1,000 (about $8,700 in 2014) to adapt the novel into a one-hour television program as part of the Climax! series. CBS famously made James Bond an American working for “Combined Intelligence” and renamed him “Card Sense” Jimmy Bond (in accordance with the name change in the American Popular Library edition). Felix Leiter became a British agent named Clarence, and Vesper became Valerie Mathis (borrowing the Rene Mathis name, but leaving Mathis out of the production entirely). The result is a long slog through an hour of clunky Baccarat scenes and enough labored exposition to choke Giancarlo Giannini. Little of Fleming’s lavish and exciting world of James Bond remained. As an example of the necessary changes made for television – rather than tying James Bond to a chair and eviscerating his testicles with a carpet beater, Jimmy Bond found himself in a bath tub while Le Chiffre’s goons plucked at his toes with pliers, off-screen only of course.

Four years later, the story fueled the first James Bond comic strip and was published in the Daily Express newspaper and syndicated worldwide. Written by Anthony Hearn and illustrated by John McLusky, the comic ran for a shade longer than seven months. Travel down the timeline another four years and rumors suggest that the legendary director Howard Hawks considered making a film based on Casino Royale in 1962 (Hawks’ biographer being the chief purveyor of said rumors), starring Cary Grant as James Bond. But this rumor becomes more complicated considering that in 1955 Fleming repackaged the rights to producer Gregory Ratkoff (most famous for his role as Max Fabian in All About Eve and director of Ingrid Bergman’s first Hollywood film, Intermezzo) for $6,000 (approximately $52,000 adjusted). Ratkoff set up a production company with actor/agent Michael Garrison and planned to move forward with production on Casino Royale in 1956. Though Fleming had reportedly written a screen adaptation for Rafkoff, the producer, apparently unhappy with the output, hired an unnamed “noted scenarist” to rewrite the script. Ratkoff passed away in 1960 without ever being able to bring the project to fruition.

After Ratkoff’s death, Charles K. Feldman of the Famous Artists production company obtained the rights from the late producer’s widow, but had no clear path to film the project himself. In 1961, Time Magazine listed From Russia, With Love as one of President Kennedy’s favorite books. As a result, sales of Fleming’s James Bond books skyrocketed in the United States and Feldman’s property became a potential blockbuster. Feldman commissioned novelist/poet/playwright Ben Hecht to write his script. Known as the “Shakespeare of Hollywood,” Hecht had written The Front Page, Underworld, Scarface and Hitchcock’s Spellbound and Notorious and contributed, without a credit, to Gone with the Wind and other Hitchcock films.

As Feldman shaped his masterpiece with the likes of Ben Hecht, however, Albert “Cubby” Broccoli (one of Feldman’s former employees at Famous Artists) with Harry Saltzman, purchased the rest of Fleming’s novels and formed EON Productions, parlaying the JFK bump into a clear and direct path to production through United Artists, which immediately began a top-of-mind-awareness promotional campaign to make James Bond a household name in North America. Newspapers received books to review, pamphlets on the Bond character and a surely titillating picture of Ursula Andress, star of the upcoming James Bond film.

EON produced Dr. No, From Russia with Love and Goldfinger before Feldman could even start production on Casino Royale. A straight take on the character now seemed impossible. Based on dates from Hecht’s notes and drafts, Hecht worked on the screenplay for Feldman as late as 1964. Watching any potential return on the rights to Casino Royale dwindle with each subsequent and hugely successful entry in the official Bond franchise, Feldman determined that the most direct route to profit was turning the project into a satire of Bond and the broader spy genre. The result, of course, is the bloated and largely incoherent, five-director feature best known for its disastrous production and behind-the-scenes feud between stars Orson Welles and Peter Sellers, not exactly a Ben Hecht film. But how much, if any, of Hecht’s work remained? Spy/suspense author Jeremy Duns located Hecht’s drafts in the Newberry Library in Chicago. Hecht had written at least four drafts of a straight Bond adventure, drafts Duns calls “a master-class in thriller-writing.” Some elements of the drafts, including assorted pages that read just like a Connery Bond film, suggest that Feldman had planned to insert his Casino Royale into the EON series, knowing he couldn’t obtain the rights to the other novels. Imagine how much differently the Casino Royale saga plays out if Feldman makes Hecht’s movie rather than leaving the reservation entirely and making the equivalent of a circus sideshow. (If you’re remotely interested in this aborted production of CR, read Duns’ Rogue Royale: The Lost Bond film by the “Shakespeare of Hollywood.”)

40 Years Later, a Return to Basics

The Brosnan era began with a new mindfulness about sexism and the frivolous reliance upon gadgets and thingamabobs. But by 00-Fluffy’s fourth time as Bond, pressure to keep up with the extreme action films of the late 90’s and early 00’s like The Matrix and XXX had too greatly influenced the series’ creative direction.

You probably recognize that Ian Fleming did not write about invisible cars or DNA-shifting North Koreans. While you probably didn’t actually read Fleming’s tepid The Spy Who Loved Me all the way through, I’ll ago ahead and reassure you that there’s nothing there about invisible cars either. (Shocking. Positively shocking, I know) As Bond attempted to keep up with cinematic trends of the 1990’s, producers fell further and further down the digital rabbit hole. Digital effects allowed filmmakers complete creative freedom. Their wildest dreams could become reality. Unfortunately for fans of the James Bond series, Die Another Day became a nightmare. While Brosnan clung to his take on the character, the tornado of impossibility swirled around his 007. Bond movies have always been at their best when their improbabilities are grounded in the real rather than the surreal. Even Moonraker, the most frivolous Roger Moore outing maintained a loose grasp on reality – despite James Bond being thrust into space. Die Another Day laid waste to the foundation of the series and realized all of the worst tendencies implicated by Natalya’s “boys with toys” quip from GoldenEye.

“Flat, distressingly witless — To put it bluntly — the thrill is gone. Nobody did it better. But that was then.” –David Ansen, Newsweek

“As a franchise, the James Bond series needs its stomach stapled.” –Michael Sragow, Baltimore Sun

“…feels like a betrayal of what the franchise has always been about.” –Todd McCarthy, Variety

Public and critical opinion weighs heavily on the minds of Bond producers. The series contains many instances of direct reaction to negative consensus and lukewarm box office. When a film strays as profoundly as Bond #20 and with such a clearly defined misstep, the reaction against the surrealism of Die Another Day became inevitable.

Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, published in 1953, became the first novel about James Bond, an agent in the British “secret service.” It offered little in the way of an origin story other than a rapid-fire introduction to all of Bond’s famous vices within the first few pages. Drink. Women. Cars. Gambling. Danger. Fleming called Bond a “compound of all the agents and commando types” he met during the war but imbued his agent with many of his own traits and personal bias. Fleming’s biographer, Andrew Lycett, suggested the Bond character had been a bit of Fleming wish fulfillment. The actual Bond origin story then perhaps might be Ian Fleming’s origin story (a bit of biography that the recent BBC production, Fleming: The Man Who Would Be Bond did a strong job of retelling while fictionalizing for mass consumption). The only concrete detail about Bond’s origin appeared in Fleming’s prose after the release of the first couple of films. Fleming added the previously untold information that James Bond was a Scotsman, to reflect Sean Connery’s nationality and tie his books more closely to the character of the films.

The pre-title sequence of 2006’s Casino Royale, thus, offered the first glimpse of a James Bond origin story, told in glorious high-contrast, grainy black and white, detailing the nature of the three kills necessary to become a 00 agent. Though the film “returns” to the origin of the character, this was not a story previously told. Had Feldman and Hecht produced their Casino Royale, this determination would likely be less clear-cut. Imagine the complications of cataloging a non-EON Bond film that actually attempted to insert itself into the series. Some might argue this could be said about Never Say Never Again, but the McClory production sought to distance itself from Octopussy in both production and marketing while remaking the story that had already become Thunderball.

Unlike the Batman, Hulk or Spiderman franchises that rehashed their origin stories, there’s no reason to suggest that this Casino Royale origin story doesn’t function as a prequel. That there’s a new Bond and a new tonal seriousness fuels the reboot argument. By that rationale, however, Roger Moore, Timothy Dalton and Pierce Brosnan all also rebooted Bond. Each changeover of actors has marked a significant tonal and/or aesthetic shift. Roger Moore changed the character more than anybody – I do not think this point can be argued – but no one, to my knowledge, has attempted to retrofit Live and Let Die with the reboot label. Daniel Craig’s Bond, on the other hand, leans heavily on precedent set by Sean Connery and Timothy Dalton – both of whom were predominantly shaped by the Book Bond from Fleming’s prose.

The Referential Dilemma

While Die Another Day referenced overtly every other Bond film, Casino Royale abandoned the litany of homages to produce a film less beholden to nostalgia. Casino stands (almost entirely) alone. I hear the Rebootists merrily thumbing their nose, feeling quite pleased with themselves now that I’ve provided supporting evidence for their argument. In turn, however, I’m going to toss out a word that might strike fear into the hearts of casual readers that just wanted to read some idle puffery about James Bond rather than revisiting a sophomore literature class. Semiotics. Most broadly, semiotics is the study of sign making through indication, likeness, metaphor, symbolism and communication. In Elements of Semiology, Roland Barthes, calls the cinema a complex system of semiology because it engages “different substances.” The senses collect and correlate images, sound and the written word through the screenplay, in efforts to decode second-order meaning, e.g. signs, symbolism and reference.

Each sign contains two components: the signifier and the signified, in other words, the image and what the image represents. Without again going into further detail about the eccentricities of interpretation of “the sign” across multiple authors and philosophers, I will remain at the surface of the term, using only this basic interpretation to make a point about Casino Royale’s intentions to impress familiarity upon the viewer. Though I must admit I’m tempted to bring Carl Jung into play to discuss the relationship of the collective unconsciousness and personal consciousness as it informs the Bond series’ relation to shared nostalgia but most of you would likely just change the channel and Post-Jungians will crawl out of the woodwork like cockroaches. My studies in semiotics are too far removed to engage in all out semiological warfare.

Instead, allow me to paint a picture.

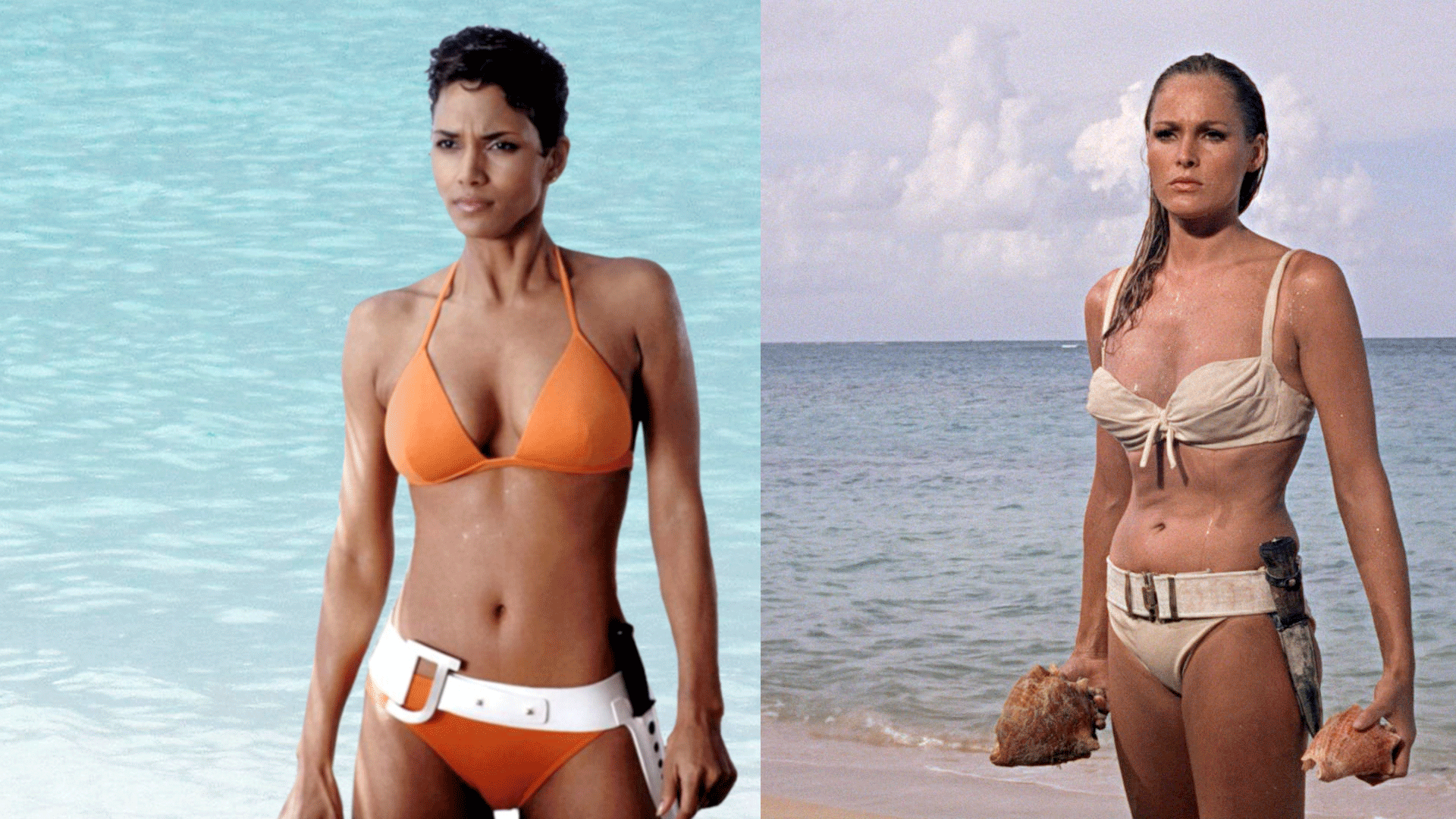

Daniel Craig as James Bond steps out of the ocean spray, his glistening pectorals causing women to swoon at 100 paces. That’s the image apparent to our naked eye. But that’s not the full, signified content. This scene directly recalls Ursula Andress emerging from the sea in Dr. No. The viewer injects this meaning, this reference, thus connecting the 21st Bond film with the 1st. And while Craig has stated that the scene was a bit of happenstance, claiming that he swam awkwardly into a sand bank and had to stand up rather than continue swimming forward and off-camera, as viewers we cannot remove our prior experience or our unconscious response when interpreting the familiar image. Die Another Day calls attention to the same reference with greater pomp and circumstance. Halle Berry sports a two-piece bikini similar to Ms. Andress’ in Dr. No and emerges from the ocean with greater swagger. The scenes in question, according to the nature of semiotics have two levels of interpretation: the scene at face value and the scene’s representation, a recall to Ursula Andress, a reference to a Bond movie from 1962.

If we force the term “reboot” to remain true to the meaning of the term as it was used in and appropriated from computer science, there could be no reference to Dr. No in Casino Royale.

But again the filmmakers don’t overtly reference the film!

This is correct. But at the same time, they know precisely which scene we’re going to associate with Daniel Craig emerging from the ocean in his light blue swimming trunks. If we take it one step further, we can also associate those light blue trunks with the light blue swimsuit Connery wore in Thunderball. The past of James Bond is inescapable in that the series is so rooted in tradition and knowing reference, but even if you deny the semiological relevance of the “ocean emergence” scene in Casino Royale or even Bond winning the Aston Martin DBS V12 (explicit reference to the Aston Martin without using the original Goldfinger car) at cards, let’s continue on into Quantum of Solace and Skyfall to seek further ties. If Casino Royale, Craig’s debut acts as a reboot, the films that follow, logically, also must continue to remain free from the knowing shackles of nostalgia.

But they just can’t help themselves, and we can’t help but insert our own experience into the proceedings. Quantum of Solace recalls one of the most iconic scenes in James Bond history when the devious eco-baddies execute Agent Fields by dipping her in oil and splaying her out across the hotel bed like Jill Masterson painted gold in Goldfinger. Unlike Craig coming out of the water, the death of Strawberry Fields relies not on vague association. The explicit connection between Fields and Masterson requires no mental leaps and serves no other narrative purpose than reference.

Skyfall performs its series of homage more skillfully, but nonetheless, the desire to return to the films of the past remains, and the viewer remains willingly complicit.

Ben Whishaw, the new Q (a cyber-strategist programmed for the modern world of digital terror), teases Bond when he dispatches only a simple firearm, “Were you expecting an exploding pen? We don’t really go in for that anymore.” Anymore. The exploding pen comes from GoldenEye, a very nice bit of Chekhovian audience expectation and fulfillment, but a traditionally outlandish Bond gadget.

And then we come to the elephant in he room, the Aston Martin DB5, license plate: BMT 216A. This is not just the model of the car James Bond drove in Goldfinger – because it uses the same exact license plate we must assume IT IS the car James Bond drove in Goldfinger, complete with the same modifications. Headlamp machine guns. Bulletproof chassis. Switch-filled armrest and red ejector button in the gearshift. When Daniel Craig’s James Bond retrieves the car from the garage, objectively how does it function in the narrative? Couldn’t any older car have served the same narrative purpose? Yes, of course, but it would have served that purpose without the knowing wink and ejector-seat gag played out with tremendous panache by Dame Judi Dench as M. “Go ahead, eject me. See if I care.” Apologists suggest this is the car he won in Casino Royale, but lo, dear friends, it is not. It is a plainly different model, and the film, upon the unveiling of the car, does not intend for our mind to return to Casino Royale – it intends to cloak us in the warm and fuzzy aura of pure Goldfinger nostalgia.

I submit one final note about reference before moving on. I would argue that it’s actually the most subversively slick Skyfall callback. In the final moments of the film, when Bond returns to M’s office to meet the new boss, there’s a moment of familiarity akin to returning to the womb. We’re transported outside M’s soundproof door. Moneypenny at her desk. Hat rack just to the left. The classic scene from many early Bonds. In this traditional scene where Craig’s Bond again devotes his mind and body to the service of his country, it is telling that not only does the set design directly recall Dr. No and other early Conneries, but M is again cast in traditional maleness after 17 years with a female at the helm. This is the return to classic Bondian normalcy with everything in its proper place, the “properness” established many years ago in films not so far away.

Quality Control

What we’re looking at, really, is the Batman & Robin syndrome. When a series reaches the nadir of its potential. Both Batman & Robin and Die Another Day share the same bloated and substance-deprived blockbuster disposition. Joel Schumacher sent Batman back to the days when BANG!, POW! and ZIP! accompanied every punch, kick and flip, except without the essential and innocent humor that made these graphic eccentricities welcome. The caveat, of course, is that this kind of comic-book absurdity was already coded in the caped crusader’s DNA. Not so with James Bond. Schumacher plotted a return to Batman’s, albeit using a misguided map. Lee Tamahori meanwhile unwittingly channeled the most maligned elements of the already maligned Roger Moore years as inspiration for Die Another Day. Failure necessitates change.

Nolan rebooted Batman in a modern, realistic world, aligning itself with Frank Miller’s Batman: Year One to create an original cinematic vision. James Bond doesn’t have the luxury of falling back on an ever-evolving library of comics or novels. EON doesn’t even seem inclined to dabble in the narratives written in the Bond continuation novels. When James Bond loses his way, he must return to Fleming’s original text, a refocusing that’s occurred thrice. In 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Peter Hunt attempted a literal translation of Fleming’s novel as a reaction to the wayward and self-deprecating narrative of You Only Live Twice. When EON cast Timothy Dalton in 1987’s The Living Daylights, the actor demanded that the production return to the spirit of Fleming’s original Bond character. Thus, after Die Another Day, EON should have already understood the blueprint to resurrection.

Three decisions proved absolutely critical when planning Bond 21. The first was adapting the last “officially” untapped Fleming novel. EON and MGM had previously obtained the rights to Fleming’s Casino Royale in 1999 when Sony Pictures swapped them for MGM’s rights to Spider-Man (which is mildly humorous considering that Sony purchased MGM in 2005 and distributed CR anyway). Neal Purvis and Robert Wade wrote the screen adaptation of the novel in 2004 with Brosnan as Bond. At this time, Quentin Tarantino expressed interest in directing Casino Royale as a black and white period film set in the novel’s 1950’s. The none-too-shy director has said that his conversations with EON led to the decision to move forward with Casino Royale as the next Bond film and return the series to its roots by cutting back on CGI, filming real stunts and focusing on the Bond character.

EON then returned to the director that had jump-started the franchise once before: Martin Campbell. Campbell had enacted a similar return to clarity when redefining Bond for the audience of the 1990’s in GoldenEye. As a director focused primarily on performance and less on bombast, he’d proven to be the perfect choice to twice re-engage a disenfranchised fan base.

The casting of Daniel Craig, however, had been far from a sure thing. The first two choices left little room for disagreement. A return to the basics, a return to Fleming? Absolutely! Martin Campbell? Of course! Daniel Craig? Eh….

Though Michael G. Wilson at one point claimed that he’d compiled a list of 200 potential James Bonds including Goran Višnjić, Henry Cavill, Sam Worthington and Karl Urban, EON appeared decisive in casting the against-type Craig. Craig had rejected an earlier offer to play the role because he felt the series had strayed from what made it great. It wasn’t until Craig read the script that Wilson was able to convince him to sign on. After signing on for the role, Craig read all of Fleming’s novels and consulted advisors on the set of Munich. He said, “Bond’s a killer. There’s a look. These guys walk into a room and very subtly they check the perimeter for an exit. That’s the sort of thing I wanted.”

The result of these three definitive decisions put everyone on the same path, making the same movie. As a result Casino Royale hits all the right marks and speaks directly to our nostalgia for Sean Connery and an original interpretation of a Fleming text. The way Bond was, the way he should be. Experiencing Casino Royale for the first time feels like movie magic – the melding of old and new – without substantively changing Bond’s DNA – just as Nolan had done with Batman one year earlier, with one major exception. Nolan rewrote his franchise from the beginning, using only the narrative elements he’d put into play. A new world, a new franchise. He pressed Ctrl – Alt – Delete (control – command – eject for the Mac users out there) and never looked back at Tim Burton’s frothing Penguin or Joel Schumacher’s cacophony of puerile nonsense.

Accusing these films of trading heavily in nostalgia does not equal criticism. Far from it, actually. The viewer wants to be in on a sly joke. The movie winks. The audience winks back. The James Bond series has been a two-way communication between the filmmakers and fans for decades now, arguably since George Lazenby looked straight into the camera and said, “This never happened to the other fella.”

007’s past cannot be removed from the present, no matter how many actors assume the role of “world’s most famous secret agent.” Change his style, tone, suit designer, watch brand, cigars, cigarettes, drink of choice, CIA contact, hair color, eye color, physique, former martial status, shoe size, choice in cabana wear – you’ll still be dealing with the very same character and the same cinematic universe. We might not all agree on how all of these movies are tied together – Whovian time lord, individual events in the life of one 00 agent, events of multiple 00 agents all called 007 – but because we, as a collective fanbase, have no desire to hit the reset button on James Bond, there never has and likely never will be a “reboot” of the franchise. Leave that term with the comic book franchises of fleeting relevance that require a forced restart after hitting a creative wall after only three or four films. Bond doesn’t need a do-over – he occasionally just needs a fresher face and a more fashionable suit. There’s just too much history between us.

Previous James Bond #Bond_age_ Project Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall / Spectre

Thank you for the absolutely fascinating bit of Bond history. So many twists and turns! I guess you could say that Craig’s Casino Royale was Bond on a diet (to remove the Brosnan-era flab). Very enjoyable.

The one thing that has always amazed me about people deciding to remake, reboot, whatever, is that when it comes to Bond, anything goes! It never seems to matter what they do so long as it is well made and James Bond, everything else is just …stuff. That is so cool!

Bond is outside the scope of remake or reboot or whatever they want to call it. When you boil Bond down to the essentials you really only need two things and the rest of it generally falls into place — a creative villain and an actor that enjoys playing James Bond. When Connery lost interest in YOLT and DAF (also poor villains), the movies sagged. Even bad Bonds are made watchable by game leading actors. Though I consider Die Another Day to be the worst of all Bonds, I take pleasure in Brosnan’s performance because he devoted himself to the role despite the nonsense around him.

And thank you for hosting the Snoopathon! A brilliant idea to bring all these spy fanatics together… and provide an instant library of reading material.

I’m so happy the snoopathon led me to your wonderful (and comprehensive) selection of Bond essays. I can’t wait to read through them all, you have such an interesting and informed take on the franchise. I was one of the skeptics when Daniel Craig was announced as Bond, but he’s gone on to be one of my faves, certainly rebooting the series in the best way possible…

Thank you so much for reading, Vicki! The #Bond_age_ project has been a great success and I hope you enjoy reading through both my essays and the My Favorite #Bond_age_ entries from the project contributors.