Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #15: The Living Daylights – Bizarro Bond in a Brave Old World

by James David Patrick By definition a litmus test is a simple test of the alkalinity or acidity of a substance using a strip of litmus paper. The term is often bandied about in politics when interrogating a potential candidate for public office, the answer to which, theoretically, would prove telling about his/her potential appointment or nomination. During the last round of U.S. Supreme Court hearings, you couldn’t turn on cable news without hearing it. The “Litmus test” question has also become a favorite figurative term in the spheres of social media and speed dating. For our purposes we’ll concern ourselves only with the former. You may use the latter on your own time. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.)

In the context of social media, especially in the Twittersphere, where characters come at a premium, and fair, in-depth explanations are often supplanted by brevity and histrionics, the notion of the litmus test has gained popularity (even if people don’t know they’re necessarily engaging in litmus tests) especially when discussing movies, music, video games, etc. The takeaway here is that lists are fun and catalyze all sorts of conversation.

I became more aware of the unspoken litmus test phenomenon when one of the great movie gurus on Twitter – @bobfreelander of the website Rupert Pupkin Speaks – posted a friend’s three-movie litmus test on his Facebook page. He had shared the list because it contained Joe Dante’s The ‘burbs, an infamous “flop” whose reputation has grown over the years as audiences are finally, after more than 20 years, discovering that the flick is wickedly funny. So it goes that if you’re a big fan of The ‘burbs, you might use someone else’s opinion of the film to gauge their character/taste in movies. I started to think about my own Three-Movie Litmus Test (capitalized for officialness).

Disagreeing with anyone’s selection is less damning than it is merely fodder for further discussion. Even within my conversations about James Bond I’ve noticed a number of recurring Bond films that speak volumes about someone’s particular approach to the Bond series. And once again, if I were going to pick three Bond films to gauge Bond compatibility*, I’d haul out this oft-contested trio: Thunderball, For Your Eyes Only and Licence To Kill.

By definition a litmus test is a simple test of the alkalinity or acidity of a substance using a strip of litmus paper. The term is often bandied about in politics when interrogating a potential candidate for public office, the answer to which, theoretically, would prove telling about his/her potential appointment or nomination. During the last round of U.S. Supreme Court hearings, you couldn’t turn on cable news without hearing it. The “Litmus test” question has also become a favorite figurative term in the spheres of social media and speed dating. For our purposes we’ll concern ourselves only with the former. You may use the latter on your own time. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that.)

In the context of social media, especially in the Twittersphere, where characters come at a premium, and fair, in-depth explanations are often supplanted by brevity and histrionics, the notion of the litmus test has gained popularity (even if people don’t know they’re necessarily engaging in litmus tests) especially when discussing movies, music, video games, etc. The takeaway here is that lists are fun and catalyze all sorts of conversation.

I became more aware of the unspoken litmus test phenomenon when one of the great movie gurus on Twitter – @bobfreelander of the website Rupert Pupkin Speaks – posted a friend’s three-movie litmus test on his Facebook page. He had shared the list because it contained Joe Dante’s The ‘burbs, an infamous “flop” whose reputation has grown over the years as audiences are finally, after more than 20 years, discovering that the flick is wickedly funny. So it goes that if you’re a big fan of The ‘burbs, you might use someone else’s opinion of the film to gauge their character/taste in movies. I started to think about my own Three-Movie Litmus Test (capitalized for officialness).

Disagreeing with anyone’s selection is less damning than it is merely fodder for further discussion. Even within my conversations about James Bond I’ve noticed a number of recurring Bond films that speak volumes about someone’s particular approach to the Bond series. And once again, if I were going to pick three Bond films to gauge Bond compatibility*, I’d haul out this oft-contested trio: Thunderball, For Your Eyes Only and Licence To Kill.

*Footnote: It should be noted that I do not expect wholesale approval for any of the films in the litmus test – in fact, only one (hint: it’s the Dalton one) of the three appear in my Top 5 Bonds. It is the full opinion of the three that acts as the strongest indicator, not a simple like or dislike**.

**Footnote’s footnote***: Failing the litmus ultimately means nothing other than humorous disagreements during live tweets (see @mentorscamper’s regular #Bond_age_ meme that I call “Carey Trowelling”).

***Footnote’s footnote’s footnote: Three levels of footnotes = pouring one out for David Foster Wallace.

Perhaps a better litmus than any collection of three movies (after all, aren’t we as Bond fans, generally amenable to most Bond movies and representations of the character?) would be one’s opinion on Timothy Dalton as 007. For many years the general belief was held that Dalton was the absolute worst Bond who made two forgettable movies as 007. (I suppose someone needs to hold the “worst” crown in a world of absolutes.) At the time of The Living Daylights’ release, contemporary critics generally lauded Dalton’s new take on the role in the wake of Roger Moore’s eyebrow’s departure. Janet Maslin wrote of Dalton:He has enough presence, the right debonair looks and the kind of energy that the Bond series has lately been lacking. If he radiates more thoughtfulness than the role requires, maybe that’s just gravy.

The Washington Post’s Desson Howe had mixed feelings on the movie but in a backhanded way praised Dalton’s change of pace:He’s spindly but energetic and enthusiastic. The eyes are scintillating, green and squinty. The accent’s as refined as Moore’s, but free of aloofness. He doesn’t have the hairy-chested exuberance of Connery, but there’s a warmth trying to get out.

And Variety added merely that “the fourth Bond, registers beautifully on all key counts of charm, machismo, sensitivity and technique.” So with all that said, from whence did this “Dalton sucks” ideology arise? To continue down this origin story as played out in film criticism, Dalton and The Living Daylights had a few prominent detractors. Roger Ebert gave the film two stars and cited Dalton’s inability “to understand that it’s all a joke.” Jay Scott of the Globe and Mail said, “you get the feeling that on his off nights, he might curl up with the Reader’s Digest and catch an episode of Moonlighting.” To that, Jay Scott, I have to question: why so much hate for Moonlighting? And why does this guy look like he watches sitcoms? In the end, contemporary film criticism holds little control over widespread public consensus. The rampant Dalton negativity stems from something deeper, a planted seed that germinated, took root and spread like wildfire, like the mint in my herb garden that I have to repel with flamethrowers by the end of every June. (Speaking of mint, don’t you think that Dalton’s Bond smells like mint, freshly shaved sawdust with a touch of Brut?) His sweetly thuggish odor, however, has no bearing on the topic at hand (this isn’t Smell-O-Vision or it’s feisty competitor AromaRama). I digress. Where did Dalton’s Bond go wrong in appealing to a wider audience? Furthermore, was it Dalton? Or was Dalton just in the wrong place at the wrong time?

In the end, contemporary film criticism holds little control over widespread public consensus. The rampant Dalton negativity stems from something deeper, a planted seed that germinated, took root and spread like wildfire, like the mint in my herb garden that I have to repel with flamethrowers by the end of every June. (Speaking of mint, don’t you think that Dalton’s Bond smells like mint, freshly shaved sawdust with a touch of Brut?) His sweetly thuggish odor, however, has no bearing on the topic at hand (this isn’t Smell-O-Vision or it’s feisty competitor AromaRama). I digress. Where did Dalton’s Bond go wrong in appealing to a wider audience? Furthermore, was it Dalton? Or was Dalton just in the wrong place at the wrong time?

Prognosis Negative

With the coming of the new Bond, EON clearly wanted to tie their new actor in with the tradition of old 007 in that first teaser poster by recalling the iconic Aston Martin. In the second poster, he’s being billed as something other than what has come before. The UK teaser says “007 at his most dangerous” while the U.S. teaser says “The most dangerous Bond. Ever,” both not-so-subtle suggestions that EON was aware of the public perception that Roger Moore’s movies had largely been a bit of puffery (an unfortunate opinion inspired largely by Moore’s final two outings). This second teaser poster distances The Living Daylights from its immediate predecessors, not just in the way it promises more “danger” but in aesthetics as well. The Bond posters had long been community affairs: James Bond prominently placed but flanked and straddled by villains, women, guns and/or explosions. They were also traditionally artwork rather than photographs. (Marketing for TLD returned to the basics for the official poster, which you can see at the beginning of this essay.) This second teaser places Timothy Dalton’s smolder front and center, medium close, so that his visage and Walther PPK occupies two-thirds of the poster. There’s no puffery to distract in this suddenly stark mug shot. Here’s the immediate takeaway: Bond is young and beautiful again, and his eyebrow is not arched in self-awareness.

The striking departure from the traditional histrionics-laden Bond artwork prefaces the (relative) seriousness of the endeavor. The photograph grounds the movie in the real, both components setting the tone for something other. The image suggests that The Living Daylights will offer the viewer a greater study of the 007 character, and indeed Dalton’s performance delivers on that promise. His version of the character projects an approximation of humanity that hadn’t been present in the superhero antics of the aging Roger Moore. EON did well to visually represent this shift through the proximity to the image of Bond, and that audiences would have been, consciously or not, directed to assume a vastly different take on the character. But despite the negativity towards Roger Moore and, in particular, his last outing in A View to a Kill, was this character shift what audiences really wanted?

With the coming of the new Bond, EON clearly wanted to tie their new actor in with the tradition of old 007 in that first teaser poster by recalling the iconic Aston Martin. In the second poster, he’s being billed as something other than what has come before. The UK teaser says “007 at his most dangerous” while the U.S. teaser says “The most dangerous Bond. Ever,” both not-so-subtle suggestions that EON was aware of the public perception that Roger Moore’s movies had largely been a bit of puffery (an unfortunate opinion inspired largely by Moore’s final two outings). This second teaser poster distances The Living Daylights from its immediate predecessors, not just in the way it promises more “danger” but in aesthetics as well. The Bond posters had long been community affairs: James Bond prominently placed but flanked and straddled by villains, women, guns and/or explosions. They were also traditionally artwork rather than photographs. (Marketing for TLD returned to the basics for the official poster, which you can see at the beginning of this essay.) This second teaser places Timothy Dalton’s smolder front and center, medium close, so that his visage and Walther PPK occupies two-thirds of the poster. There’s no puffery to distract in this suddenly stark mug shot. Here’s the immediate takeaway: Bond is young and beautiful again, and his eyebrow is not arched in self-awareness.

The striking departure from the traditional histrionics-laden Bond artwork prefaces the (relative) seriousness of the endeavor. The photograph grounds the movie in the real, both components setting the tone for something other. The image suggests that The Living Daylights will offer the viewer a greater study of the 007 character, and indeed Dalton’s performance delivers on that promise. His version of the character projects an approximation of humanity that hadn’t been present in the superhero antics of the aging Roger Moore. EON did well to visually represent this shift through the proximity to the image of Bond, and that audiences would have been, consciously or not, directed to assume a vastly different take on the character. But despite the negativity towards Roger Moore and, in particular, his last outing in A View to a Kill, was this character shift what audiences really wanted?

Bizarro Bond

The story of James Bond has always been a tale of two worlds. Much like the “The Bizarro Jerry” episode of Seinfeld, Movie Bond and Book Bond have existed, parallel to each other, living approximate but different lives. There have been moments within the films where their paths have threatened intersection. The rebellious and grieving Bond in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. The focused Bond with a mean streak in From Russia with Love and vengeful Bond in For Your Eyes Only. In the Dalton films (and Licence to Kill, especially), Book Bond and Movie Bond actually brushed shoulders. They both took seats in Monk’s Diner – one at the counter and one in a booth by the window. They both ordered coffee, black, and stewed silently. In 1987, the year of The Living Daylights’ release, Movie Bond turned 25. That’s 25 years of directing audience expectation, and even though three different actors had played Bond, the trajectory of the three had been one of increasing distance from Ian Fleming’s source material, though one could easily argue that by the time Connery vacated the post, as a result of externally-imposed political and cinematic trends and misguided creative decisions, Movie Bond had nowhere else to go but self-awareness. On Her Majesty’s Secret Service had failed at the box office in the eyes of its creators. It failed not necessarily because of it’s proximity to Fleming’s source material, but because James Bond hadn’t been Sean Connery. EON merely threw the Lazenby out with the bathwater. The rampant cynicism of the early 1970’s dictated a change. It was as much a function of the socio-political climate as it was a conscious creative direction in reaction to underwhelming box office returns. The Cold War that informed Fleming’s blunt instrument of espionage, Book Bond, had long since dissipated. In it’s stead, Movie Bond of the early 1970’s faced détente, skeptical nationalism and confused international roles and identities. A rebellion against the institution to which Bond vowed loyalty. Plots became more localized. Live and Let Die concerned U.S. drug trafficking. Despite the solar powered MacGuffin, The Man with the Golden Gun concerned little more than a battle of wits (or a pissing match, if you will) between Scaramanga and 007. When Movie Bond returned to the realm of power-crazed megalomaniacs, SPECTRE/Blofeld was no longer allowed to provide the go-to serial enemy and the Russians were intermittent allies rather than shadowy foes. Even Sean Connery’s Bond would have arched an eyebrow at this notion.The original title of War and Peace was War: What is It Good For?

With the dawn of the 1980’s came the return of the Cold War (known generally as the “second Cold War”), a shift towards conservatism catalyzed by Reagan/Thatcher relationship, the UK’s invasion of the Falklands and the US invasion of Grenada. It was as if the political climate of the West had shifted overnight. Elected partially on the strength of his hardline approach to U.S.-Soviet relations, Reagan took a proactive approach by ramping up military spending from 5.3% of the GNP to 6.5% by 1986, the largest peacetime defense buildup in United States history. He revived the lapsed B-1 Lancer program (the “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative) that had been canceled by the Carter administration. The Soviets deployed ballistic missiles targeting Europe. NATO aimed a bevy of cruise missiles at Moscow. Tension came to a head on September 1st, 1983. The Soviet Union shot down a Koren Air Lines flight with 269 passengers aboard when it violated Soviet airspace. The events immediately following led both the U.S. and the Soviet Union to fear an imminent nuclear strike and the subsequent retaliation.

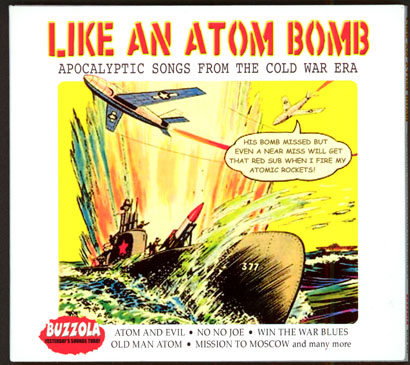

Logically, this meant that paranoia returned to the forefront the Western collective conscience. This paranoia was in turn heavily reflected in the pop-culture output of the early 80’s. Prince’s “1999,” Nena’s “99 Luftballoons,” U2’s “Bullet the Blue Sky” are just a small sample of the litany of popular songs that reflected the growing fear of nuclear holocaust. 1983 saw the release of WarGames, which predicted World War III, and The Day After, a disturbing film that detailed the lives residents in small-town Kansas in the wake of a nuclear holocaust. True to form, Bond also joined the paranoia party, fashionably late, by sneaking in the back door, because, you know, he’s a secret agent and prone to escapism rather than blatant politicizing.

With the dawn of the 1980’s came the return of the Cold War (known generally as the “second Cold War”), a shift towards conservatism catalyzed by Reagan/Thatcher relationship, the UK’s invasion of the Falklands and the US invasion of Grenada. It was as if the political climate of the West had shifted overnight. Elected partially on the strength of his hardline approach to U.S.-Soviet relations, Reagan took a proactive approach by ramping up military spending from 5.3% of the GNP to 6.5% by 1986, the largest peacetime defense buildup in United States history. He revived the lapsed B-1 Lancer program (the “Star Wars” Strategic Defense Initiative) that had been canceled by the Carter administration. The Soviets deployed ballistic missiles targeting Europe. NATO aimed a bevy of cruise missiles at Moscow. Tension came to a head on September 1st, 1983. The Soviet Union shot down a Koren Air Lines flight with 269 passengers aboard when it violated Soviet airspace. The events immediately following led both the U.S. and the Soviet Union to fear an imminent nuclear strike and the subsequent retaliation.

Logically, this meant that paranoia returned to the forefront the Western collective conscience. This paranoia was in turn heavily reflected in the pop-culture output of the early 80’s. Prince’s “1999,” Nena’s “99 Luftballoons,” U2’s “Bullet the Blue Sky” are just a small sample of the litany of popular songs that reflected the growing fear of nuclear holocaust. 1983 saw the release of WarGames, which predicted World War III, and The Day After, a disturbing film that detailed the lives residents in small-town Kansas in the wake of a nuclear holocaust. True to form, Bond also joined the paranoia party, fashionably late, by sneaking in the back door, because, you know, he’s a secret agent and prone to escapism rather than blatant politicizing.

James Bond had always been a kind of socio-political reflection of the times, but the final two Roger Moore films, though acknowledging growing tension, largely remained hands-off of the new Cold War crisis. Both Octopussy and A View to a Kill simultaneously address yet skirt the issue of failing relations between the USSR and the West, but the films could never have sustained such a drastic tonal shift as would be required. It wouldn’t have fit the personality of Roger Moore’s 007. He had been Bond during the thaw. MI-6’s relationship with General Gogol and the KGB had grown shaky but never fell in shambles. At worst the KGB had remained irresponsibly indifferent in AVTAK or irresponsibly competitive in For Your Eyes Only. Background figures with moderately irresponsible intent. Détente remained an underlying theme. But with each new 007 comes the opportunity for a series reboot, thus re-orientating Bond into a brave new world. With Roger Moore stepping down after A View to a Kill, EON took advantage of this opportunity to cast a James Bond that would possess the gravitas necessary to facilitate the requisite tonal shift. Pierce Brosnan had been their first choice, a half-step towards this gravitas, but his Remington Steele contract prevented him from accepting. NBC renewed the show at the 11th hour to capitalize on the press he’d received from the 007 casting rumors. First they put the screws on the man who would be 007 and then they cancelled Freaks and Geeks after one partial season. (They’re Eeeevil.) EON again turned to Dalton. Dalton had been approached as early as 1969 to replace Sean Connery in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Dalton turned down the opportunity because he felt he was too young and did not want the task of following Connery. He was again approached before filming began on For Your Eyes Only but he expressed concern over the direction of the series. Perhaps he didn’t find Moonraker’s “pew pew pews” quite as entertaining as we do. Now 43, he was finally ready to don the tuxedo, but first the new Bond (known henceforth as T-Dalt) had a few demands on the production.

T-Dalt read and studied the Ian Fleming books before accepting the role and it has been said that he was never far from the texts during filming. It should come as no surprise that the actor known primarily for work on the stage with the Royal Shakespeare Company and dramatic roles on the BBC, had been much concerned about delivering an honest portrayal of Ian Fleming’s original character. In an interview with the BBC in 1989, he said:

James Bond had always been a kind of socio-political reflection of the times, but the final two Roger Moore films, though acknowledging growing tension, largely remained hands-off of the new Cold War crisis. Both Octopussy and A View to a Kill simultaneously address yet skirt the issue of failing relations between the USSR and the West, but the films could never have sustained such a drastic tonal shift as would be required. It wouldn’t have fit the personality of Roger Moore’s 007. He had been Bond during the thaw. MI-6’s relationship with General Gogol and the KGB had grown shaky but never fell in shambles. At worst the KGB had remained irresponsibly indifferent in AVTAK or irresponsibly competitive in For Your Eyes Only. Background figures with moderately irresponsible intent. Détente remained an underlying theme. But with each new 007 comes the opportunity for a series reboot, thus re-orientating Bond into a brave new world. With Roger Moore stepping down after A View to a Kill, EON took advantage of this opportunity to cast a James Bond that would possess the gravitas necessary to facilitate the requisite tonal shift. Pierce Brosnan had been their first choice, a half-step towards this gravitas, but his Remington Steele contract prevented him from accepting. NBC renewed the show at the 11th hour to capitalize on the press he’d received from the 007 casting rumors. First they put the screws on the man who would be 007 and then they cancelled Freaks and Geeks after one partial season. (They’re Eeeevil.) EON again turned to Dalton. Dalton had been approached as early as 1969 to replace Sean Connery in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Dalton turned down the opportunity because he felt he was too young and did not want the task of following Connery. He was again approached before filming began on For Your Eyes Only but he expressed concern over the direction of the series. Perhaps he didn’t find Moonraker’s “pew pew pews” quite as entertaining as we do. Now 43, he was finally ready to don the tuxedo, but first the new Bond (known henceforth as T-Dalt) had a few demands on the production.

T-Dalt read and studied the Ian Fleming books before accepting the role and it has been said that he was never far from the texts during filming. It should come as no surprise that the actor known primarily for work on the stage with the Royal Shakespeare Company and dramatic roles on the BBC, had been much concerned about delivering an honest portrayal of Ian Fleming’s original character. In an interview with the BBC in 1989, he said:

I think Roger was fine as Bond, but the films had become too much techno-pop and had lost track of their sense of story. I mean, every film seemed to have a villain who had to rule or destroy the world. If you want to believe in the fantasy on screen, then you have to believe in the characters and use them as a stepping-stone to lead you into this fantasy world. That’s a demand I made, and Albert Broccoli agreed with me.

Originally written for Moore, The Living Daylights’ script had already been re-written for Brosnan and now had to be refashioned according to Dalton’s standards. Dalton wanted to portray a 00 agent conflicted with his unseemly role in the world. Like Book Bond, Dalton’s Bond performed according to his own moral code – not the code of Queen and country. Taken in context of the morally ambiguous Cold War, Dalton’s Bond could be seen as not only rebelling against his superiors but also against the morally void world in which he existed. Our governments were no longer our salvation. Each man could only rely on himself. This marks a drastic departure from the Roger Moore Bond films, which were frequently concerned with nationalism and “keeping the English end up.”Superman probably has a very good sense of humor

“I think Superman probably has a very good sense of humor. He’s got super strength, super speed, I’m sure he’s got super humor.” -Jerry

Do I dare reintroduce the James Bond/superhero conversation? Consider the deliveries of some iconic post-execution one-liners in the James Bond series.

In Dr. No, Connery forces a car full of thugs off the edge of a cliff. A construction worker steps up to ask him “What happened.” Bond responds, “I think they were on their way to a funeral.” Pause for chuckle. People died in a fiery scrap of metal. It’s a horrible death!

Moving on to Thunderball. One of Largo’s henchman approaches through the trees, without much stealth mind you. Domino whispers to Bond “Vargas behind you.” Bond turns and shoots him through the gut with a speargun. “I think he got the point,” he says.

Amidst the pew pew pew pew. Pew. Pew pew pew climax of Moonraker, Bond confronts Drax in his lemon yellow space suit. Drax pulls a space gun (that presumably also goes pew pew pew). Bond acts first, shooting him with a dart from his wrist gun. “Pardon, Mr. Drax,” he says before opening the escape hatch and ushering the stunned villain inside. In this instance, Moore’s Bond issues his wit pre-execution. “Take a giant step for mankind,” he says as he dispatches him into deep space. Drax is already incapacitated and likely mortally wounded, but just to be sure, Bond shuttles him into space where he will, presumably, experience a gruesome final moment from which the viewer has been spared. A death worthy of a philosophical disciple of Hitler. But this elaborate wordplay, as displayed in Moonraker and Live and Let Die are not human reactions to violence. They are, in part, both sociopathic and superhuman.

Don’t misinterpret the logic here. Part of the appeal of the James Bond character is the extreme danger and violence, made palatable for consumption by adding humor, style and panache. From a critical perspective, however, it is important to disassociate the various components in order to consider the methods of the various Bond actors. Connery’s Bond spoke less; he was a blunt instrument that more often reacted rather than pro-acted. Afterward he would dull the impact with a sharp retort, no more than an aside. He grapples for his life and then composes himself so entirely that puns and entendre roll off the tongue with perfect ease and a standing pulse. A display of his calm, perhaps superhuman response under pressure.

The quintessential Connery retort takes place in Goldfinger’s pre-title sequence. Connery’s Bond enters his room, a naked woman waiting for him having just stepped out of a bath. She’s merely a distraction, used to allow an assailant to sneak up from behind. Bond sees his approach in the reflection on the woman’s eye. They grapple. Bond slings him into the bathtub and when the thug reaches for Bond’s gun, 007 slaps a table lamp into the water. The goon fries in the tub, steam rising from the water, enveloping his writhing body. Connery has barely broken a sweat. As Bond returns the gun holster to his shoulder, he delivers arguably the most iconic one-liner in the history of James Bond. “Shocking,” he says before turning to regard the weary woman now on the floor. “Positively shocking.” Connery’s Bond delivers these lines with relish, off-the-cuff, like nothing really horrible has happened at all.

Roger Moore’s Bond, however, delivered punchlines rather than asides, like the deaths were part of the joke. Consider the above-mentioned scene in Moonraker. In Live and Let Die Kananga rises to the ceiling like a helium-filled balloon and explodes. Moore’s Bond: “He always did have an inflated opinion about himself.” The one-liners like the movies themselves had an undercurrent of self-awareness that undermined the brutality with wordplay and elaborate humor. Set up. Execution. Punchline. Raised eyebrow. Roger Moore’s Bond strays from this formula most notably in For Your Eyes Only – a movie that could also be considered Moore’s darkest turn as 007 – when he kicks Emile Leopold Locque’s car off a cliff. The scene carries gravitas because Locque isn’t just a typical Bond henchman/adversary (henchversary?). The largely mute Locque has been given a significant backstory (by Bond henchman standards). He’s a criminal, convicted of strangling his psychiatrist and greatly enjoys his work as an assassin for Kristatos. That he barely speaks only enhances our perception of him as a grim psychopath. By the time Bond finally has the opportunity to dispatch Locque, the assassin has struck Bond more personally. Locque organized the killing of Countess Lisl, a woman for whom Bond had developed some amorous affection. From our perspective it would be no great stretch to suggest that this scene planted the seed for Dalton’s Bond, a Bond as controversial as this one much-debated scene.

“I think Superman probably has a very good sense of humor. He’s got super strength, super speed, I’m sure he’s got super humor.” -Jerry

Do I dare reintroduce the James Bond/superhero conversation? Consider the deliveries of some iconic post-execution one-liners in the James Bond series.

In Dr. No, Connery forces a car full of thugs off the edge of a cliff. A construction worker steps up to ask him “What happened.” Bond responds, “I think they were on their way to a funeral.” Pause for chuckle. People died in a fiery scrap of metal. It’s a horrible death!

Moving on to Thunderball. One of Largo’s henchman approaches through the trees, without much stealth mind you. Domino whispers to Bond “Vargas behind you.” Bond turns and shoots him through the gut with a speargun. “I think he got the point,” he says.

Amidst the pew pew pew pew. Pew. Pew pew pew climax of Moonraker, Bond confronts Drax in his lemon yellow space suit. Drax pulls a space gun (that presumably also goes pew pew pew). Bond acts first, shooting him with a dart from his wrist gun. “Pardon, Mr. Drax,” he says before opening the escape hatch and ushering the stunned villain inside. In this instance, Moore’s Bond issues his wit pre-execution. “Take a giant step for mankind,” he says as he dispatches him into deep space. Drax is already incapacitated and likely mortally wounded, but just to be sure, Bond shuttles him into space where he will, presumably, experience a gruesome final moment from which the viewer has been spared. A death worthy of a philosophical disciple of Hitler. But this elaborate wordplay, as displayed in Moonraker and Live and Let Die are not human reactions to violence. They are, in part, both sociopathic and superhuman.

Don’t misinterpret the logic here. Part of the appeal of the James Bond character is the extreme danger and violence, made palatable for consumption by adding humor, style and panache. From a critical perspective, however, it is important to disassociate the various components in order to consider the methods of the various Bond actors. Connery’s Bond spoke less; he was a blunt instrument that more often reacted rather than pro-acted. Afterward he would dull the impact with a sharp retort, no more than an aside. He grapples for his life and then composes himself so entirely that puns and entendre roll off the tongue with perfect ease and a standing pulse. A display of his calm, perhaps superhuman response under pressure.

The quintessential Connery retort takes place in Goldfinger’s pre-title sequence. Connery’s Bond enters his room, a naked woman waiting for him having just stepped out of a bath. She’s merely a distraction, used to allow an assailant to sneak up from behind. Bond sees his approach in the reflection on the woman’s eye. They grapple. Bond slings him into the bathtub and when the thug reaches for Bond’s gun, 007 slaps a table lamp into the water. The goon fries in the tub, steam rising from the water, enveloping his writhing body. Connery has barely broken a sweat. As Bond returns the gun holster to his shoulder, he delivers arguably the most iconic one-liner in the history of James Bond. “Shocking,” he says before turning to regard the weary woman now on the floor. “Positively shocking.” Connery’s Bond delivers these lines with relish, off-the-cuff, like nothing really horrible has happened at all.

Roger Moore’s Bond, however, delivered punchlines rather than asides, like the deaths were part of the joke. Consider the above-mentioned scene in Moonraker. In Live and Let Die Kananga rises to the ceiling like a helium-filled balloon and explodes. Moore’s Bond: “He always did have an inflated opinion about himself.” The one-liners like the movies themselves had an undercurrent of self-awareness that undermined the brutality with wordplay and elaborate humor. Set up. Execution. Punchline. Raised eyebrow. Roger Moore’s Bond strays from this formula most notably in For Your Eyes Only – a movie that could also be considered Moore’s darkest turn as 007 – when he kicks Emile Leopold Locque’s car off a cliff. The scene carries gravitas because Locque isn’t just a typical Bond henchman/adversary (henchversary?). The largely mute Locque has been given a significant backstory (by Bond henchman standards). He’s a criminal, convicted of strangling his psychiatrist and greatly enjoys his work as an assassin for Kristatos. That he barely speaks only enhances our perception of him as a grim psychopath. By the time Bond finally has the opportunity to dispatch Locque, the assassin has struck Bond more personally. Locque organized the killing of Countess Lisl, a woman for whom Bond had developed some amorous affection. From our perspective it would be no great stretch to suggest that this scene planted the seed for Dalton’s Bond, a Bond as controversial as this one much-debated scene.

Though the scene with Locque was somewhat of an anomaly for Moore’s Bond it was by no means an isolated incident. Moore had shown glimmers of this nasty streak in each of his earlier films. The execution of Locque comes without any fanfare. He is unarmed and in a vulnerable position. James Bond approaches the car as it teeters on the edge of a cliff, Locque scrambling within for exit via the passenger-side door, and gives it a swift kick. There’s a slight but perceptible difference in delivery of the following line. “He had no head for heights,” he says. No set-up for the joke. The punchline remains but it lacks the fanfare and forced theatricality. That’s an acid tongued retort born from a very human emotion: revenge. And in fact, Roger Moore objected to the scene suggesting that his Bond wouldn’t have done such a thing… but perhaps Roger is forgetting how he let a henchman fall off a roof and used a woman as a human shield in The Spy Who Loved Me. Nevertheless, these were largely passive executions. The act of kicking Locque’s car off the cliff showcased Bond’s licence to kill like no other scene since the execution of Dent in Dr. No. The punchline does not dull the moment or eclipse the very human response to the horrors Bond has experienced.

Now consider the following scene from Licence to Kill that contains, in my mind, the quintessential T-Dalt Bond execution. Bond stuffs the villain into an incubator drawer full of maggots. He quips, “Bon appetite.” There’s snarl in his voice and the act is distasteful. The line contains humor, but Dalton does not play it for laughs. Pay close attention to the timing of the delivery. Much like the execution of Locque, Bond leaves no room for the chuckle, the nudge nudge, or the wink wink. This is cold-blooded execution. The post-execution aside does not undermine the real horror of the act. Dalton brings his character down to wallow in the slop and horror associated with murder and death. Within the Bond franchise, we expect to be thrilled in a climate-controlled environment where sex and violence are made safe for mass consumption. I’m not saying, necessarily, that Dalton breaks the thermostat, but he does fiddle with it when nobody’s looking. Dalton, in this scene especially, leaves the viewer a little bit squirmy. Many fans will brush the moment aside and call the line a “groaner” because the quip doesn’t dull our distaste to the on-screen violence.

Though the scene with Locque was somewhat of an anomaly for Moore’s Bond it was by no means an isolated incident. Moore had shown glimmers of this nasty streak in each of his earlier films. The execution of Locque comes without any fanfare. He is unarmed and in a vulnerable position. James Bond approaches the car as it teeters on the edge of a cliff, Locque scrambling within for exit via the passenger-side door, and gives it a swift kick. There’s a slight but perceptible difference in delivery of the following line. “He had no head for heights,” he says. No set-up for the joke. The punchline remains but it lacks the fanfare and forced theatricality. That’s an acid tongued retort born from a very human emotion: revenge. And in fact, Roger Moore objected to the scene suggesting that his Bond wouldn’t have done such a thing… but perhaps Roger is forgetting how he let a henchman fall off a roof and used a woman as a human shield in The Spy Who Loved Me. Nevertheless, these were largely passive executions. The act of kicking Locque’s car off the cliff showcased Bond’s licence to kill like no other scene since the execution of Dent in Dr. No. The punchline does not dull the moment or eclipse the very human response to the horrors Bond has experienced.

Now consider the following scene from Licence to Kill that contains, in my mind, the quintessential T-Dalt Bond execution. Bond stuffs the villain into an incubator drawer full of maggots. He quips, “Bon appetite.” There’s snarl in his voice and the act is distasteful. The line contains humor, but Dalton does not play it for laughs. Pay close attention to the timing of the delivery. Much like the execution of Locque, Bond leaves no room for the chuckle, the nudge nudge, or the wink wink. This is cold-blooded execution. The post-execution aside does not undermine the real horror of the act. Dalton brings his character down to wallow in the slop and horror associated with murder and death. Within the Bond franchise, we expect to be thrilled in a climate-controlled environment where sex and violence are made safe for mass consumption. I’m not saying, necessarily, that Dalton breaks the thermostat, but he does fiddle with it when nobody’s looking. Dalton, in this scene especially, leaves the viewer a little bit squirmy. Many fans will brush the moment aside and call the line a “groaner” because the quip doesn’t dull our distaste to the on-screen violence.

You got me blacklisted at Hop Sing’s

This Seinfeld reference is less apt, but still applies. Just roll with it. It might come as no shock that For Your Eyes Only has become one of the more controversial movies in the entire James Bond series. Fans cited specifically Bond kicking Locque off the cliff as a point of contention. Beneath some of the jokey Moore staples lies a darker undercurrent of revenge and humanity. The villains in FYEO aren’t megalomaniacs looking down from ivory towers (read: lairs); they’re charlatans and mentally imbalanced psychopaths with backstory. They’re real people—much like the variety that would populate the brand of James Bond movie that Timothy Dalton wanted to create. With the lukewarm reception of For Your Eyes Only in mind then, does it come as a tremendous shock that Timothy Dalton and his two films The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill have been met with such indifference or, in extreme cases, loathing? At this point in time, it seems that the audience would not allow Bond to breach his role as an escapist entertainer. The reflection of the Cold War’s moral ambiguity in the 007 films proved unwelcome. Permit me the oversimplification of 1980’s popular culture in order to distill its essence into a few sentences. The decade became known as “the Me Decade” because of the frivolous expenditure on personal goods, rising debt, brand name recognition and worship. I’ve read the argument that this “splurge generation” (as dubbed by novelist Tom Wolfe) came as a result of the “live like it’s your last day on earth” mentality. And as a result of the threat of nuclear holocaust many people did believe this mantra. Spending became the 1980’s version Prozac. This notion of instant gratification manifested itself in all facets of popular culture. The 1980’s ushered in bubble-gum pop-music and brought about the rise of purely escapist blockbusters. The top ten grossing movies of the decade include: The Return of the Jedi, The Empire Strikes Back and the three Indiana Jones movies. Sci-fi, action, thriller and fantasy films rose in popularity. It was the golden age for the teen comedies, buddy cops and sequels. Genre experienced a rebirth and the stark, contemplative cinema of the 1970’s slipped into the background. It would be nearly impossible to distinguish the tone or political underpinnings of The Living Daylights, taken out of context, from any other of the other escapist fare mentioned above. We are only able to single out Dalton and his two Bond entries because of what immediately preceded them in the Bond series. As it was originally written for Roger Moore, The Living Daylights contained many of the traditional James Bond tropes. Over-the-top action set pieces, a deadly Soviet assassin, the fully equipped Aston Martin (the V8 Vantage in this instance), and a key ring that fires stun gas, opens pretty much any lock and has a wolf-whistle-detonated explosive charge. But rather than a raised eyebrow, T-Dalt approaches the proceedings with tongue firmly in cheek, perhaps too firmly for mass audiences. Dalton played a character close to Book Bond, and Book Bond never went into the field with entendre and pun in addition to his Walther. In Michael Marano’s meditation on why Timothy Dalton was the best James Bond (in the essay collection James Bond in the 21st Century), he cites a passage from the Basil Rathbone film Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror to explain why Dalton failed in the eyes of the moviegoing public. Holmes says to Watson (Nigel Bruce): “Good old Watson. You are the one fixed point in a changing age.” It is Bond’s blandness, his blank slate and minimal development that he suggests allows the character to adapt to the needs of the contemporary audience. And while I think this is largely true at the point of Dalton’s 1987 debut (Skyfall has complicated this assertion to an extent), the further backstory of this specific quotation makes for even more interesting commentary. The extended exchange between Holmes and Watson has been lifted, nearly verbatim from the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle story “The Last Bow.” The film was the first Rathbone Holmes to take place in the 1940’s instead of the late 1800’s. Universal tried to explain the time shift at the beginning of the film with the following title card:“The character of Sherlock Holmes, created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, is ageless, invincible, and unchanging. In solving significant problems of the present day, he remains, as ever, the supreme master of deductive reasoning.”

Does that sound like anyone we know? Rathbone wanted to update the series for the modern era because he thought the stories from the 1800’s were growing stale. To facilitate the shift, the filmmakers gave Rathbone a ridiculous haircut and a fedora rather than his traditional deerstalker. The 1942 film, set during the build-up to WWII, involves the plot of a Nazi spy impersonating an English aristocrat (lifted from the novel The Great Impersonation by E. Phillips Oppenheim which was set during the first World War). In that the film was still inspired primarily by “The Last Bow,” the Doyle estate made certain demands that the film production remain partially truthful to Sir Arthur’s source material. The result of these demands, among many other small concessions, was the aforementioned moment when Holmes calls Watson a blank slate. As I assume you’re all at least partially versed in the various Holmes cinematic adaptions and thus refrain from detailing the many incarnations of the famous detective. The wellspring of comparisons between the James Bond and Sherlock Holmes franchises runs deep. Literary figures with multiple incarnations across many different actors over more than 50 years of television and cinema. Thus Holmes’ assertion can be applied to inform the immediate negative response to Dalton. Timothy Dalton was the first Bond to inject a more specific, less malleable personality. T-Dalt’s Bond had his own point of view. He rebelled against authority, at times with immature petulance. His integrity, this inverse morality of the frightening world of 1980’s politics, not only molded Movie Bond into something new but also the world in which he existed. The violence became more real as did Bond’s reaction to the violence and horror around him. But why does this mean necessarily that Bond’s audience would rebel against the Dalton Bond and The Living Daylights? This unfortunate standoffish relationship has endured now for nearly thirty years. While it’s easy, at face value, to write off TLD as a failed reboot, take a closer look. M and Q were not re-cast. They occupy traditional roles and personalities. The Bond formula, as established in Goldfinger (with the exception of the three-Bond-girl component) remains, perhaps in a more efficient package than any film since The Spy Who Loved Me. In another much-discussed series shift, James Bond becomes *gasp* monogamous, reflecting perhaps the growing concerns over AIDS. The series attitude toward female co-stars, however, doesn’t change accordingly. Maryam d’Abo remains arm candy, but unlike many other Bond girls, she has thoughts and motives independent of Bond’s mission. I’ve read criticisms of Dalton’s Bond that suggests his seething demeanor resulted in unseemly verbal Bond-girl abuse. Bond’s frustration of d’Abo’s Kara Milovy does stand out during the climax of the film (but let’s admit she turns into a helpless dolt and kind of deserves it), but I would argue this is the perfect balance for Bond and a demeanor that Connery embraced fully in Dr. No and From Russia With Love. Bond ought not to care what anyone thinks of him, not the audience and not the (likely) vapid woman he has to drag around for two hours. Mark Young of Sight and Sound summarizes this thought perfectly, “For Bond there should be only allies, enemies, and the light glaze of contempt that spreads over the remainder of the world.”Top of the Muffin to you!?

The fact remains that you simply cannot have a muffin top without a muffin bottom. If there’s no muffin bottom, the muffin top is merely just a muffin. Someone has to deal with the muffin-bottom problem. In refashioning James Bond, Timothy Dalton went back to the roots on the character, before 007 became a pawn in larger more unbelievable theatrics. He found the passion and intensity that endeared Book Bond to so many readers. Sean Connery had it prior to Goldfinger. And Daniel Craig has it now. Without Timothy Dalton’s book-based portrayal of the character, does Daniel Craig’s Bond happen at all? Prior to the release of Skyfall, Timothy Dalton was interviewed by the Los Angeles Times about the direction the Bond franchise had taken. He said, “There’s a case to be made that Daniel Craig is the best Bond ever, or at least in a very long time.” He goes on to suggest that Connery remains the greatest Bond. “Daniel Craig’s Bond movies are,” he says, “the legitimate heir of Dr. No and From Russia with Love.” One can’t help but wonder if Dalton is giving himself enough credit in this equation. Dalton provided the stepping-stone Craig used to create his dour, thoughtful and human character. Consider Daniel Craig’s 007 to be an extension of Dalton’s steadfast assertion that the future of James Bond lied in a return to the character’s roots. “I would have died to have done [the first 25 minutes of Casino Royale],” Dalton said. It should be impossible to embrace the new Bond without respecting the foothold gained by Timothy Dalton’s bold, ballsy debut in The Living Daylights and his Bond Gone Wild in Licence to Kill (LtK’s theme of rebellion against the institution echoed throughout Casino and Quantum of Solace). We’re left with that question of torment. What if? What if Dalton had been given better material? A reign not shortened by uncertainty and MGM’s pending financial ruin? Ultimately these what ifs are wasted on frustrating conjecture. More apparently, 1987, as it clung to its unconscious desire for escapist entertainment, just wasn’t ready for the T-Dalt smolder… no matter how it was packaged or presented. In every dead-eyed, bloodshot Daniel Craig stare we’re finally witnessing the conclusion of Timothy Dalton’s unfinished symphony. Get it? Symphony? Cello? You didn’t think you were going to escape all this rabble about The Living Daylights without mention of the cello, did you?

End note: Bonus points for being able to pick my brain about why Seinfeld resonated so strongly with The Living Daylights. Leave theories in the comments. YES. There was actually a reason for the Seinfeld barrage.

Get it? Symphony? Cello? You didn’t think you were going to escape all this rabble about The Living Daylights without mention of the cello, did you?

End note: Bonus points for being able to pick my brain about why Seinfeld resonated so strongly with The Living Daylights. Leave theories in the comments. YES. There was actually a reason for the Seinfeld barrage.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks