This is the 20th essay in a 23-part series about the James Bond cinemas. I encourage everyone to comment and join in on an extended conversation about not only the films themselves, but cinematic trends, political and other external influences on the series’ tone and direction.

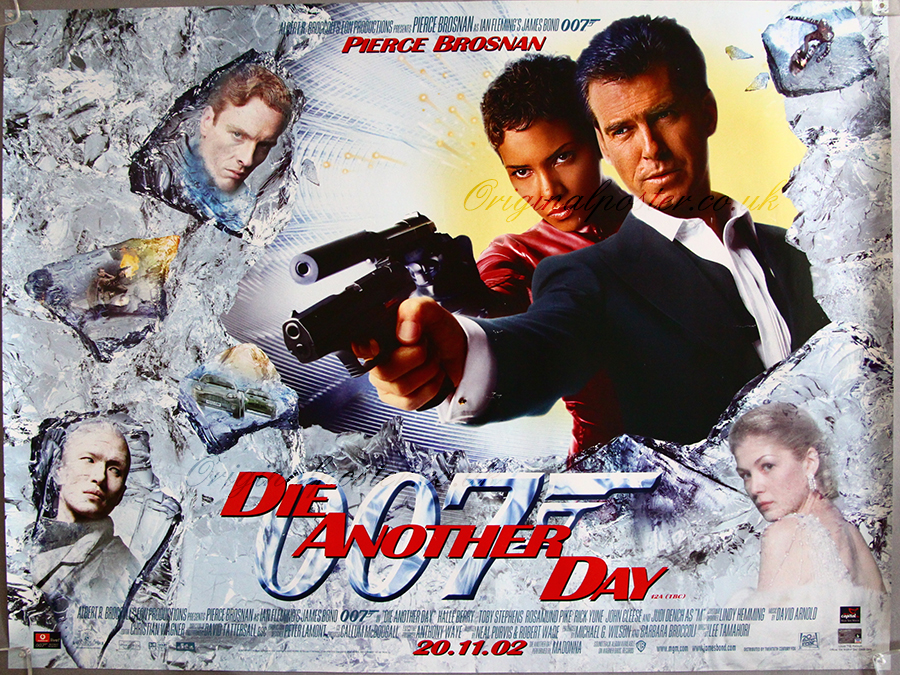

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #20: The Tortured Mind of James Bond: Die Another Day and the Fever Dream

by James David Patrick and Matt Finch

Bond fans will engage at great length in pleasant debate regarding their favorite Bond film. They will champion GoldenEye as their favorite feature while also conceding to a fellow conversant that From Russia With Love is also a respectable choice, despite wholehearted disagreement. There’s an unspoken respect between Bond fans. You like Bond. I like Bond. Let’s be BFFs (Bond fans forever, obviously). It’s secret rule of Bond appreciation 1.97.C-35. Fellow Bond fans can like any Bond movie with impunity.

Tongues of Bond fans become more silver-tipped when discussing their least favorite Bond film. Bad Bonds slept with your mother, rubbed lemon juice in your paper cuts, took the last radish from the crudité. The danger here isn’t crucifying a Bond that someone loves (See subsection 4 under rule 1.97.C-35: Every Bond film has something “objectively lacking”). The danger is not hating a particular Bond movie enough. Oddly, this isn’t covered by one of the unwritten laws or subsections. Pick Diamonds Are Forever as your least favorite pick, prepare for hostility.

“Octopussy! The clown suit!”

“The World Is Not Enough. Christmas f’ing Jones!”

“Misogyny AND racism! Live and Let Die!”

Still, there’s one Bond that passes almost any Bad Bond litmus test. And that movie, as you might expect, is Die Another Day. I’ve been talking Bond on Twitter for a long damn time now. There’s one assertion that’s never, ever met with much resistance (I say “much” because that bold Bond fan Michael Cavacini remains on the front line of DAD defense – he’s the frontline, the entire army and commanding officer). Let’s get one thing out of the way before we go any further. Die Another Day is subjectively and objectively the least good James Bond movie. That’s called being diplomatic. Even those that have a more favorable opinion of the film accept that the movie represents a significant transgression in the Bond canon.

But a transgression from what exactly? Bond movies have always performed a tenuous tightrope act – the balance between the real and the surreal. Consider the titles that most often come up in the battles of the worst Bonds: Moonraker. Octopussy. A View to a Kill. Die Another Day. What do they all have in common? The movies most often deemed “the worst” overstep the bounds of acceptable suspension of disbelief. They lose the grounded reality of a British intelligence officer investigating threats to Western interests.

What if there was an explanation for these wild departures from the grounded real? What if these “bad Bond” transgressions could be explained with a measure of intertextual analysis courtesy of everyone’s favorite French literary theorist, philosopher and semiotician, Roland Barthes. What if some of the James Bond films were just 007’s daydreams, nightmares or memory traces, engrams, or post-traumatic stress welling up from within a man, who, for fifty years now, has endured violence, death and loss as part of his daily regimen?

These “what ifs” had been percolating for months on Twitter in a conversation with Matt Finch, and I wanted to find an avenue to bring this fascinating discourse to the masses. As I approached the end of my series of #Bond_age_ essays, I became haunted by potential angles for Die Another Day. How could I avoid the negativity that plagues most conversations about the film? Throughout the series I’ve done my best to highlight positives and explain how an individual film functions within the greater scope of the entire James Bond series. When Matt and I again turned our conversation of Barthes’ myth back to the anomalous Die Another Day, I knew that we needed to finally put this dialogue on paper.

As the most phantasmagoric episode in the franchise, Brosnan’s final Bond offered the surreality necessary to provide fodder for our dream theories. The film’s mix of past and present, reference and homage played out like a greatest-hits reel. Visions and fears, past successes and failures returned as latent imagery of a mind riddled with post-traumatic stress. Halle Berry recalling Honey Ryder. In Q’s gadget room, Bond finds the Aerostar mini-plane and crocodile disguise from Octopussy, the Thunderball jetpack. Rosa Klebb’s shoes even. One wonders when Bond started taking souvenirs from his fallen victims. The Aston Martin with ejector seat. Blink and you’ll miss the Union Jack parachute from The Spy Who Loved Me and Little Nellie from You Only Live Twice.

Yes, yes, of course. I know what you’re saying. But EON just jam-packed all those references into Die Another Day to “celebrate” the 40th anniversary of Bond. Forget all that. Forget the more practical, real-world pandering done by the filmmakers at the expense of the movie’s narrative drive. Instead let’s suspend our disbelief a little further. And as Bond fans, we should be adept at that by now. Let’s consider for a second that these outlier Bonds, these erratic, anomalous “lesser” Bonds are actually the fever dreams of a fragile, post-traumatic stress-addled mind of 007.

I. Origins of the “Fever Dream Theory”

Matt Finch:

I saw A View To A Kill again recently. Even as a child, I knew this was the first definitively rubbish Bond film I’d ever seen. It plods along; its pace is set by racing horses and airships. Moore’s Bond looks about as old as his chauffeur Sir Godfrey! And on this last rewatch, I realised that elements of the film chimed with my childhood favourite, The Spy Who Loved Me.

In the opening ski chase in AVTAK, Bond “surfs” on a single ski to the sound of a godawful Beach Boys cover. It’s a distorted version of famous sky chase at the beginning of The Spy Who Loved Me. At the close of the sequence, a babe in a ridiculous iceberg-submarine rescues 007. It’s another echo, this time of Bond’s final canoodle in TSWLM‘s plush lifeboat.

Bond films have always repeated themselves, but this seemed like an all-new low. It borders on self-parody. Perhaps, as I suggested to you on Twitter, AVTAK is just a bad dream that the younger Bond is having? Premonition and memory swirl together while 007 is unconscious, drugged by Barbara Bach in 1977.

This blend of repetition and anticipation within individual Bond films is more than just a fancy. Each film adheres to, or deviates from, the ‘Bond formula’ in some measure. As you wrote in your essay on Bond ‘reboots’, there’s no meaningful continuity within the series. Its elements form a kaleidoscope, rather than a coherent sequence.

In your reboot piece, you brought in the semiotician Roland Barthes to discuss this. In his collection Mythologies, Barthes argues that a myth derives its meaning from structure. The repetition of the mythic structure then serves to naturalise certain ideological assumptions. We see this mythic repetition in Bond movies, too. There’s the pre-credits sequences from an unrelated adventure, the first girl he seduces dies, etc, etc. Sometimes, the repetition is so direct that it’s painful: The Spy Who Loved Me is a blatant recycling of You Only Live Twice, etc, etc.

James David Patrick:

There’s a section in Barthes’ Image / Music / Text regarding Eistenstein’s Ivan the Terrible. It is the Barthes myth applied to an image (rather images) from Ivan.

In this conversation, “The Third Meaning,” Barthes discusses the image at face value – the first meaning, the action on screen. The second meaning considers the symbolic. The third, the meaning beyond words, the myth of the image. He goes on to clarify in this argument that the differentiation between the second and the third meanings is the same as the obvious vs. the obtuse. He says:

“…the third meaning also seems to me greater than the pure, upright, scant, legal perpendicular of the narrative, it seems to open the field of meaning totally, that is infinitely… the obtuse meaning appears to extend outside culture, knowledge, information; analytically, it has something derisory about it: opening out into the infinity of language, it can come through as limited in the eyes of analytic reason; it belongs to the family of pun, buffoonery, useless expenditure. Indifferent to moral or aesthetic categories (the trivial, the futile, the false, the pastiche), it is on the side of the carnival.”

It occurs to me in these episodes of James Bond, especially Die Another Day, which lay bare the Bond mythology dispatch this second meaning. Most of the film’s absurdities come about at the expense of narrative. If the narrative maintains forward motion it must do so at the expense of the reference. I return (again!) specifically to Halle Berry emerging from the ocean. The theatricality of the emergence calls attention to the artifice, to the expressly referential nature of the image. The scene neither develops her character nor furthers the narrative. Compare the Die Another Day scene with that of Ursula Andress in Dr. No. The ocean and the land of Jamaica defined Honey Ryder — she was a scavenger, living off the land, eating the local vegetation and harvesting shells. Thus the emergence furthers the narrative. Honey Ryder as a symbol of post-Colonial Jamaica remains in tact. Meanwhile Halle Berry backdives into a sea of CGI, a jarring image that compounds the artificiality of the reference when compared to the naturalism of Honey Ryder’s moment in Dr. No.

In DAD, the symbol and the myth become inextricably linked – in the reference and the nostalgia for the old Bond films, which is, of course, the purpose of reference. I suppose, however, that because a scene that functions first as a reference and second (very distantly, if at all) as narrative, the ties between the symbol and the myth become much stronger and ever more apparent in their artifice. This calls back to Casino Royale (‘67), Austin Powers, etc., the films that use parody and reference as the path to humor rather than the warm fuzzies of familiarity (though there’s always a loving element of the latter in all great parody).

II. The Anti-Auterism of 007

JDP:

First used in connection with the French New Wave films of the mid 1950’s, Auteur theory suggests that a director’s creative and personal voice will emerge despite the collaborative, cacophonic process of filmmaking. Critics of auteur theory (Pauline Kael, for example) denied that auterism existed in a studio system. Auteur theory’s impact (or lack thereof) on James Bond falls in line with Pauline Kael’s theory that the auteur is suffocated by the system. In Bond’s case, however, it’s the formula that suffocates the auteur.

Bond directors, screenwriters and actors must perpetuate the myths laid out before them. The constants in the Bond series are 007, the myth and the formula. In this context, we can expand the formula to include form and structure: the gun barrel, the three Bond girls, Monty Norman’s James Bond Theme and familiar refrains (“Bond, James Bond”). Some Bond movies manage to incorporate myth into the individual narrative. Others, like Die Another Day, present the myth as the focus.

The cumulative effect of foregrounding the symbol-myth is that Die Another Day journeys further into the realm of the surreal, rather than walking the tightrope of the grounded real. The worst Bond movies reach a critical breaking point where they supplant the real with the surreal and plummet from that high-wire act. With little continuity between movies – the perpetual turnover of directors, actors – some variance must be expected. New minds will enforce their creative visions. The rigid constraints of the EON-enforced formula dilutes auterial vision and promotes mythmaking.

You Only Live Twice. Moonraker. Die Another Day. Octopussy. A View To A Kill. In these now familiar examples, the perpetual need to outdo while acknowledging previous entries (the aforementioned mythmaking) compounds the artificiality and surreality of the Bond universe. As the films become more surreal, they become more dreamlike and less tethered to the grounded real. Only through superficial reference do we associate Die Another Day with Dr. No, films separated by 40 years and connected only through the name of our protagonist. With that in mind, how removed is a farce like Casino Royale (1967) from the Bond canon? CR67 devolves into a tenuously linked series of referential vignettes that culminate in a wild, illogical climax. This same description could apply verbatim to Die Another Day. Taking the CR67 connection one step further, many different directors and writers worked on the film, lending to the disconnect between vignettes. Casino Royale acts as a microcosm of the entire Bond series. Auterism discarded in favor of bacchanal revelry.

MF:

I love Casino Royale, as you know. The film’s kaleidoscopic qualities and “zaniness” allow it to comment directly on a world in which there are multiple James Bonds (one of them has even ‘gone into television’). The movie Bonds range in suavitude and competence from Woody Allen to David Niven via Peter Sellers and Terence Cooper. Cooper is chosen to become James Bond after Miss Moneypenny is invited to select the most desirable man in the British secret service – Bond discussed, within his own film, as object of female desire long before Daniel Craig emerged from the waves. (Even if the scene itself is more puerile and less feminist than you’d wish). Even David Niven’s fussy patrician Bond serves to remind us of the character’s roots in a pre-WWII world and the delusional fantasies of the British Empire during an era of dwindling colonial power. And Sellers’ Bond fascinates because he’s an ordinary bloke, not stupid and not without talent, who finds himself in the uncomfortable situation of impersonating an impossible, infallible superstud.

There’s arguably less to enjoy about Die Another Day than CR67, but it has a similarly disconcerting, kaleidoscopic feel – all the more so because of its advent-calendar approach to celebrating the Bond films’ fortieth anniversary.

III. More on the Grounded Real vs. Surreal

MF:

Die Another Day is so daft that it lays bare the repetitive structure of Bond. Every element on screen serves not the story but the wider myth. It has the all-time weirdest Bond car, which turns invisible on command. The Anglo-American ‘special relationship’ gets sexualised. And the baddie is a “foreign devil” infiltrating the British body politic by rewriting his own DNA!

You can’t pretend Die Another Day is successful entertainment for most viewers. It’s like a bad dream of a Bond film. But who wakes from a nightmare and doesn’t find food for thought in their lingering visions? When Madonna coos, “Sigmund Freud, analyse this,” she’s telling us to see the movie as a dream!

JDP:

When Bond strays from the grounded real, the movies take on varying degrees of self-parody. Though many fans overlook this because of the Connery lobster trap, the second half of You Only Live Twice became the first misstep into the surreal. The assault on the volcano lair. Japanese Bond. Little Nellie. Blofeld. The Aryan henchman. All of these things, though not as egregiously as what would come later, take on the laughable air of the absurd via retread and self-parody. But they do so because they are plainly recycled elements – not yet aged enough for lovable reference and therefore lacking the broadest value of Barthes-style mythmaking. The elements represent formula. Roald Dahl admitted working on the You Only Live Twice screenplay with a Madlib-style screenwriting approach due to the constraints imposed upon him by Cubby Broccoli and Harry Saltzman:

“Bond has three women through the film: If I remember rightly, the first gets killed, the second gets killed and the third gets a fond embrace during the closing sequence. And that’s the formula. They found it’s cast-iron. So, you have to kill two of them off after he has screwed them a few times. And there is great emphasis on funny gadgets and love-making.”

Why has YOLT escaped the same widespread criticism as Moonraker and Die Another Day? YOLT may be an important consideration in terms of revealing the nuts and bolts of the formula from the earliest stages of creation.

MF:

Do you believe that You Only Live Twice begins the transition to the Bond formula proper? Does it set a template for later films: a baddie bent on world domination, a final assault accompanied by Bond’s marine/solider/ninja allies?

JDP:

I’d go as far to say that the seeds of the Bond formula were scattered throughout Dr. No as well. There’s an evolution of the same narrative-forming methodology. Of those early Bond films it’s From Russia With Love that becomes a definitive outlier, and in many ways remains so today – the proximity to the source material, a claustrophobic train-bound climax where the protagonists and antagonists are bound together on the same linear path. Neither takes on the traditional roles of offense and defense the standard lair assault. It’s not something we consider now, looking back on 52 years and 23 films, but how often can you say that the third film in the series became the most popular and ultimately catalyzed the entire franchise? Goldfinger set a precedent. I believe that having labored on the lesser side of financial success with the first two films, the Bond producers focused on the individual elements of Goldfinger and attempted to carry those into Thunderball while simultaneously upping the ante. They wanted to take the audience somewhere new and thrilling. We tend to forget how wildly innovative those underwater scenes in Thunderball were in 1965. Audiences had never seen anything like it. Modern Bond fans overlook that until Skyfall, Thunderball had been the highest grossing Bond film (adjusted) ever. When Thunderball became even more successful than Goldfinger, the formula became gospel, etched on a paper napkin while Cubby bathed in Bolly and consumed North-of-the-Caspian beluga caviar. Good opening weekend returns encourage this behavior.

Today Twitter response regarding Thunderball focuses on the languorous underwater scenes. Thunderball has become a more familiar punching bag from the Connery films than even You Only Live Twice, which as we’ve discussed is largely a farce. It does not take a long-winded essay (perhaps this one?) to see that in emulating the movies that had come before it, YOLT teeters over the precipice of parody much in the same way as Die Another Day. In this context, I would argue that Thunderball is the most perfect iteration of the formula and You Only Live Twice represents the formula gone stale. So while You Only Live Twice wasn’t the first film to employ the Bond formula it feels like the first film to operate under the formula’s rigid constraints. It’s also the first film to eschew the Fleming narrative. Dahl called it Fleming’s worst novel and considered it unfilmable. Dahl’s script tosses the narrative and consequently feels rudderless without it, hopping from one boilerplate scene to the next. Once we finally reach the lair assault, Bond’s turned Japanese (terribly), gotten fake/real married (say what?) and led a screaming ninja assault on Blofeld’s volcano hideout. Bond does nothing proactive through this final third of the film – he’s carried along by the burdensome demands of the formula. When you reach the carbon copy of this lair assault in The Spy Who Loved Me, 007 participates in the battle and appears to risk life and limb beside his nameless, faceless army of naval crewmen. This comparison recalls my earlier mention of how certain Bond movies foreground myth while others assimilate.

Consider the Aryan henchman lifted directly out of From Russia With Love (but this time without any distinguishing characteristics or introduction) – and again when this familiar character is regurgitated much later with Stamper in Tomorrow Never Dies. The screenwriters have given Stamper stuff to do, lines to say, fear to generate. Another favorite: the quick piranha for shark substitution for the easy dispatch of unruly henchmen and maybe possibly perhaps Bond. It’s not the fact that the Bond formula has been employed – it’s the startling lack of creativity. The seams shouldn’t be exposed to the audience unless operating in the realm of straight reference or parody. I’d argue that A View to a Kill, despite recycling the Goldfinger narrative and lifting scenes directly from that film does a better job of hiding the formula through the creative use of the individual elements. Consider the villains, Christopher Walken’s Max Zorin and Grace Jones’ Mayday. As I discussed in my essay on A View to a Kill, Mayday represents a hulking obstacle to 007, one that threatens the dominant male hierarchy of the entire series. By hypersexualizing Jones’ character, this allows filmmakers to tap into two very distinctive sexual encounters between Mayday and Max Zorin (masochism) and Mayday and Bond (awkward interracial coupling). The latter falls directly in line with the Three Bond Girl Formula — but it doesn’t feel prefabricated. It feels brand new. Creepy, but brand new.

In this respect, You Only Live Twice, as a Frankenstein monster of recycled spare parts has more in common with Die Another Day than any other Bond film. The former, however, becomes an unwitting self-parody while the latter consciously regurgitates reference in the name of Bond’s 40th anniversary.

IV. The Diamond Lining of Die Another Day

JDP:

One might argue that the value of Die Another Day could be derived from enjoying the film’s isolated vignettes. The fencing scene. Q’s homage-laden gadget workshop. The driving stunts on ice. The film even begins with a deft bit of screenwriting – Bond taken into captivity, tortured and detained as a prisoner of war by the North Koreans. The opening offers much to be admired. (Mute Madonna’s title track.) The hovercraft pre-title scene, especially compared to the CGI spectacles that would eventually follow, provides an early thrill that places 007 in real peril. As you mentioned earlier, this is James Bond operating for the first time in a post-9/11 world. The Cuban scenes even allow some downtime for Brosnan to enjoy being Bond — something he rarely gets to do. He gets cleaned up, browbeats some hotel employees and smokes a Cuban cigar. Like Licence to Kill and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, Bond has again gone rogue, only this time without the residual thrills of operating out of MI-6’s scope. Once Bond returns to service, however, the movie shifts to surreal escapism and the early, gritty realism proves to be a tease of a better movie we never get to see. The drastic tonal and surreal shift into gene replacement, invisible cars, parasurfing and ice palaces fits perfectly into the theory that all of this takes place in the tortured mind of 007 during his incarceration. 007 mind, like Die Another Day, has been broken.

The more I’ve thought about the 007 “Fever Dream,” the more it all fits — and not just in the realm of wild analysis. These lesser transgressions that trade heavily on Barthes’ myth take place in the mind of 007. But how does this inform our reading of these bad Bonds? For me the most interesting idea that comes out of Die Another Day is this bit of pub fodder that pertains to our fever dream theory: Does Bond ever leave North Korea? With a bit of revisionist timeline theory, one could argue that Die Another Day represents the death of 007. The end of the series. The end of our now embattled and broken hero. The Daniel Craig movies that follow return to an origin story in Casino Royale. Not merely because the Bond producers wanted to return to Bond’s roots in the last remaining novel by Ian Fleming, but because Bond could not possibly go forward.

MF:

“If we shadows have offended,

Think but this, and all is mended,

That you have but slumbered here

While these visions did appear.”

Is Brosnan thus the most puckish Bond? …I love it.

JDP:

Absolutely. But does that mean that Dalton is Nick Bottom?

Previous James Bond #Bond_age_ Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall