This is the 17th essay in a 24-part series about the James Bond cinemas co-created by Sundog Lit. I encourage everyone to read the other essays, comment and join in on the conversation about not only the films themselves, but cinematic trends, political and other external influences on the series’ tone and direction.

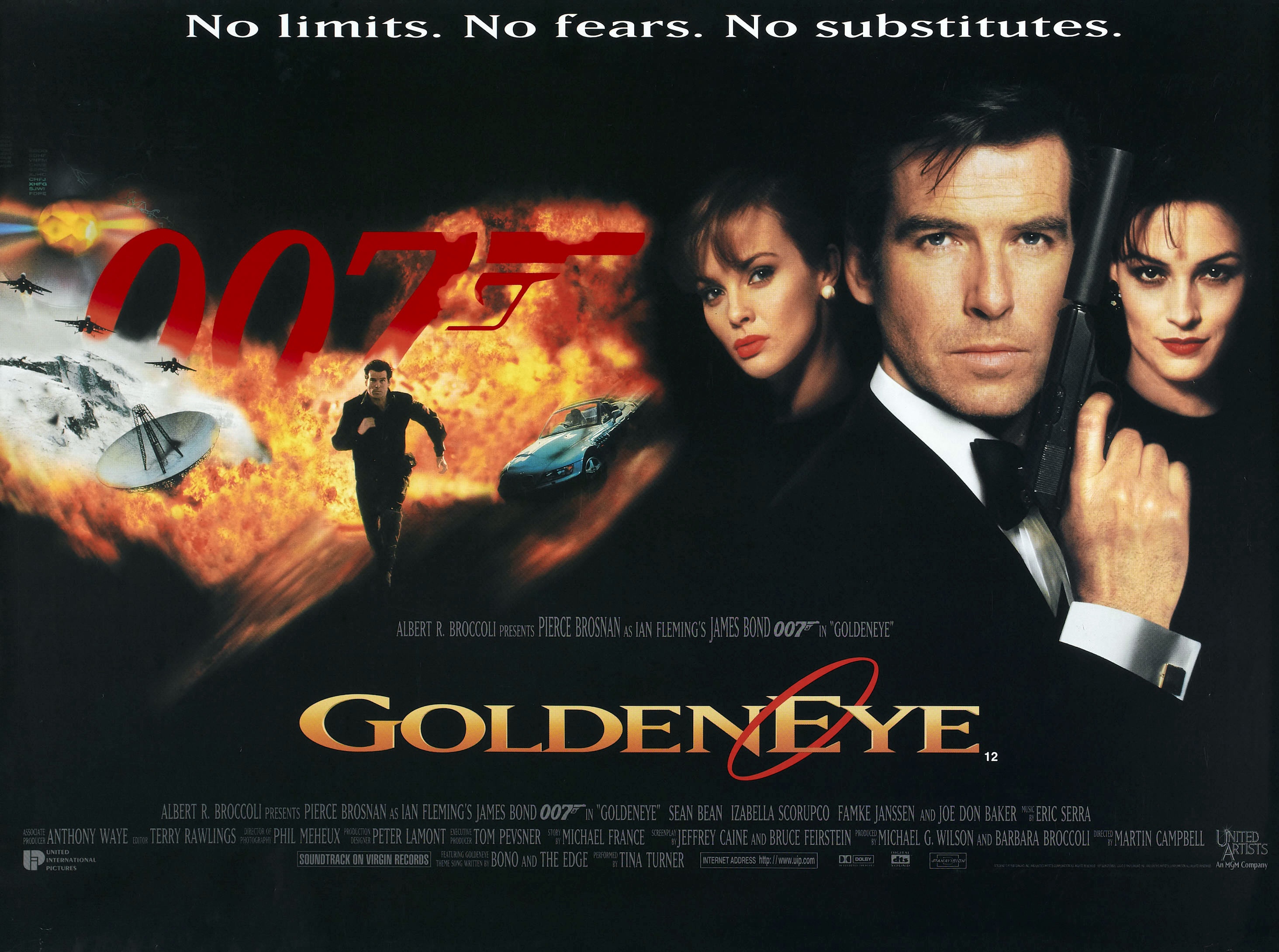

Of [In]human #Bond_age_ #17: From the Ashes, The Twisty Tale of GoldenEye’s [Un]Certain Success

by James David Patrick

Although the popularity of the Bond franchise has endured 50 years, that popularity has not been without its share of crescendos and diminuendos, ebbs and flows and disappearances. The critical mass has called for the series’ demise on a number of occasions, and MGM’s ongoing financial crisis has regularly thrown monkeywrenches into the gears of the finely tuned machine. The six-year delay after Licence to Kill led many fans to believe that Bond had officially retired after going off the reservation in Licence. Disillusioned by the bureaucracy, the agent formally known as 007 living out the remaining years of his life running a bail bonds/chicken wing joint in Jamaica. But what transpired during that dark, uncertain time period may have actually revived the franchise.

Licence to Kill tanked at the box office. Perhaps as a result of the drastic tonal shift, perhaps as a result of box-office competition from a jam-packed multiplex. Licence opened on July 14th, 1989, drawing only $13 million that week and finishing fourth at the box office behind Batman (total gross: $251 million), Lethal Weapon 2 (total gross: $147 million) and Honey, I Shrunk the Kids. Ghostbusters II, released the month prior, pulled almost $7 million… and Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, two months after it’s release, earned $7.38. By the week of August 4th -10th, LtK had dropped out of the Top 10, trailing all of the aforementioned movies except Ghostbusters II. Adjusted for inflation, the film’s return ranks dead last among Bond films, and Dalton’s other effort, The Living Daylights, bests only A View to a Kill and Licence to Kill. I wouldn’t be too quick to demonize The Smolder just yet, however. The bottom four Bond movies ranked by adjusted gross were all released during the 1980’s. It wasn’t that moviegoers had necessarily disconnected with Timothy Dalton (though he regularly plays the patsy); moviegoers had just disconnected with Bond altogether. The rise of the blue-collar action hero shoved our dapper spy back into the shadows. The new guard, the John McClanes and Martin Riggses, average Joes who woke up one day with their localized world falling apart, latched onto a zeitgeist and dominated the domestic box office.

The Delay that Unhinged a Studio

Cubby Broccoli, too, had become disappointed with the direction of the series. He had always used fan support as a barometer for success. Therefore, the diminishing returns weighed heavily on his conscience.

His first order of business after Licence to Kill was dismissing longtime screenwriter Richard Maibaum and director John Glen. Shortly thereafter, Maibaum passed away on January 4th, 1991. A heart attack. He’d contributed to 13 James Bond screenplays beginning with Dr. No and ending with Licence to Kill. The only Bonds in which he didn’t have a hand? You Only Live Twice, Live and Let Die and Moonraker. Maibaum was the writer that had shaped the James Bond cinema franchise from the ground up. In an article Maibaum wrote after Goldfinger, he said the movie character retained Fleming’s image of a “super sleuth, super fighter, super hedonist, super lover,” but that the filmmakers had added an element vital to Bond’s big screen success: humor. If not the heart of Movie Bond, Maibaum may have been the liver, replaceable, but not without great discomfort. In his stead, Broccoli had commissioned a screenplay from Cliffhanger scribe Michael France and set out to find a new director.

Meanwhile, back at MGM/UA, desperation spread through the ranks like influenza. The suits grew restless and resorted to schoolyard bullying, but the kind of bullying that takes place at prestigious boarding schools. One kid acts a little tough and the other threatens a corporate takeover: “My dad could buy out your dad!”

Bond had been MGM’s cash cow, a regular influx of cash that had kept the studio afloat (but just barely) for many years. Without a Bond picture on the horizon and only Rocky V ready for release (sidenote: how awful must it feel to pin all of your hopes on the prospects of Rocky V after having seen it?), the future of the company looked bleak. In desperation, the MGM/UA chairman panicked. He sold the company to the Australian-based broadcasters Quintex who in turn looked to merge with Pathe Communications. Days before the merger, Danjaq (the EON holding company) formally objected, issuing a writ against MGM/UA and its new chairman (Italian businessman Giancarlo Peretti) to prevent the transfer of rights from the Bond back catalog to Pathe. Cubby believed that Pathe planned to merely unload Bond’s TV rights in order to fund the ongoing MGM buy out, an action that would prevent EON from generating revenue from any potential TV licensing.

Further behind the scenes, another McClory conspiracy was brewing. You likely remember Kevin McClory, thorn in Bond’s backside, but should you need a reminder… he and Ian Fleming wrote a Bond screenplay prior to Broccoli and Saltzman purchasing the rights to produce Dr. No. Fleming then went ahead and used that screenplay to create his Thunderball novel. McClory sued for rights to all things Movie Bond and came away with the rights to SPECTRE, Blofeld and the content of the original Thunderball screenplay (which eventually became the film Never Say Never Again). McClory’s delusions of grandeur again returned to the Thunderball reservoir, hoping to produce yet another James Bond film. But back to this in a minute.

Pierce Brosnan, now free from the shackles of Remington Steele, bided his time, anxious to play the role of James Bond with two new roadblocks in his way. With EON still supporting Dalton and MGM’s financial future on life support, Brosnan watched his prime Bond years trickle away. Brosnan confessed to being unable to watch The Living Daylights upon its release in the theater and later confessed to Larry King that he only watched it on a transatlantic flight several months later, a captive audience. Always the opportunist, McClory tried to repackage the already repackaged Thunderball rights into a brand new Bond movie called “Warhead 8.” His pitch? Pierce Brosnan as Bond. But the project never gained traction as it battled a lawsuit from EON who claimed that the movie fell outside the scope of the original settlement. While the battle over “Warhead 8” played out, McClory further parlayed his Bond rights, selling a slice to producer Al Ruddy who began developing a James Bond television show in early 1992 and also wanted to cast Brosnan. EON, of course, filed another lawsuit to cease production. They were again successful. That same year, Die Hard-producer Joel Silver confessed that he too wanted to acquire the rights to James Bond to make his own film with Mel Gibson in the lead role. Some reports suggest that Silver went as far as offering Gibson $15 million to play Bond as a way to jumpstart the project, hoping that pressure from public interest would spur the project along. Everyone it seemed had a unwanted hand in the 007 cookie jar.

As his legal battles dragged on, Cubby’s health also began to fail as a result of a chronic heart condition. The MGM/UA (now MGM/UA Pathe) situation remained unsolved. New chairman Frank Mancuso appointed John Calley as president of UA. Calley had been at Warner Bros. for the production of Never Say Never Again and his first matter as chief was to force Bond back into production. He gave Cubby a list of four acceptable names for the new James Bond: Hugh Grant, Ralph Fiennes, Liam Neeson and Pierce Brosnan. Broccoli defended his Bond, insisting that Dalton would finish his three-picture contract. This stasis continued until 1993 when MGM/UA replaced the overbearing businessman Giancarlo Peretti with a production group more willing to handle Bond on Cubby’s terms.

Once convinced that the rights to all things Bond would remain within the family, Albert R. Broccoli announced he would take a back seat for the production of Bond 17 and officially passed the production torch to Michael G. Wilson, Cubby’s stepson (who had been an executive producer since Moonraker) and his daughter Barbara. But four years after the release of Licence to Kill, EON still had no forward momentum on a new Bond film.

Another year passed without anything more than idle speculation and media rumormongering. On April 11th, 1994 Timothy Dalton formally resigned the role. Though he had not filmed his final contracted film, Dalton’s contract had a termination clause where he could walk away without obligation after so many years. The Smolder wanted to move on. His announcement formally severed ties with the labored production of Bond 17 that still had no timetable to begin filming. EON supported his decision and began the brief search for his replacement. Ten actors tested for the role – nine of them unnecessarily. Dalton’s successor was a foregone conclusion; he’d been tabbed for the role since he first met Cubby on the set of For Your Eyes Only. Finally on June 1st 1994, as Pierce Brosnan was setting off to film an adaption of Robinson Crusoe, he received the phone call that he was to report to duty on the set of Bond 17, now officially titled GoldenEye. In full Crusoe beard, Brosnan held a press conference to make the casting official.

The Re-“Modernisation” of a “Sexist, Misogynous Dinosaur”

Everything, including the wild conceptualization of the action sequences, the impudence, the sexual pugnaciousness and the willingness to have a little fun at the expense of the hero, is pushed a bit further than it has been recently, serving to shake loose whatever cobwebs might have gathered and enable this new Bond to establish his own identity.

-Todd McCarthy, Variety

Perhaps our popular conception of maleness has changed so much that James Bond can no longer exist in the old way. In “GoldenEye,” we get a hybrid, a modern Bond grafted onto the formula.

-Roger Ebert, Chicago Sun-Times

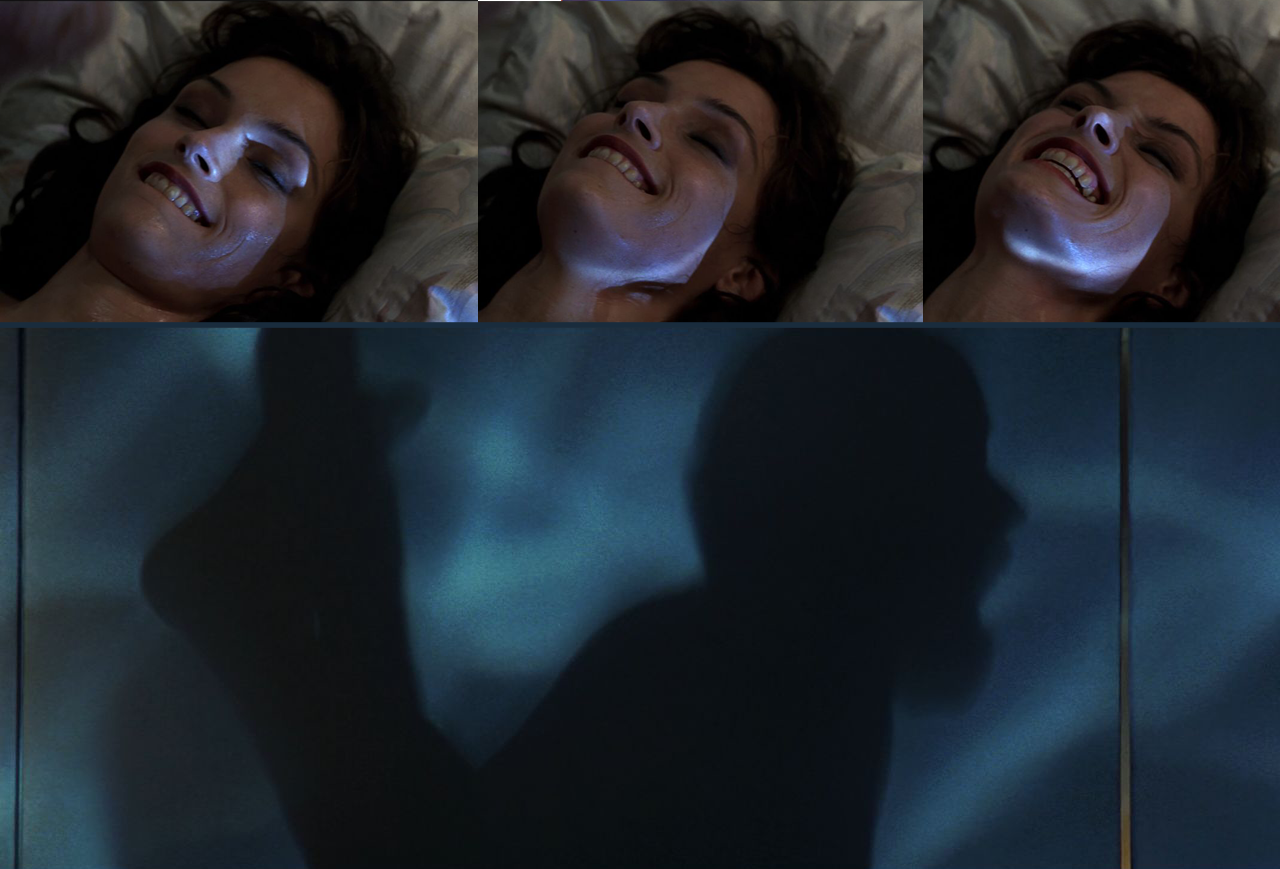

Sprinkled throughout the movie are references to the new power of women. Bond gets accused by his latest flame, Natalya (Izabella Scorupco), of being cold and scared of commitment. He has to endure Moneypenny’s japes about sexual harassment. And, most entertainingly, he comes up against the Russian assassin Xenia Onatopp (Famke Janssen), a psycho vamp who combines the lethal movements of Bruce Lee with the sexual fantasies of Madonna, crushing victims to death in the midst of orgiastic S&M bouts.

-Owen Gleiberman, Entertainment Weekly

In many ways, Bond of the 1990’s faced similar hurdles to Bond of the 1970’s. The prevailing winds of competing cinema had kicked up, requiring reinvention, or more accurately a recalibration. The same elements remain, in largely the same order… except that the jokes that normally might have been made at the expense of the Bond girls were now made at the expense of Bond’s beautiful leading man… by GoldenEye’s Bond women. Brosnan’s Bond inserts himself into the joke. As Judi Dench’s M berates him for being a “sexist, misogynous dinosaur,” he takes it with knowing aplomb and no offense, at complete ease in his £3,000 Brioni suit and peroxide smile, dripping with self-awareness in a post-True Lies, post-Cold War, post-feminist cinematic landscape.

It’s a fitting anecdote then that Roger Moore showed up on set one day demanding that Brosnan vacate the set because the old guard had been sent to take over the struggling production. Roger Moore, ever the spirited connoisseur of good-natured ribbing, had merely stopped by to visit his son Christian who was working as a third assistant director on the movie.

I briefly return to the criticism of Dalton’s Bond that the actor played the role like he didn’t know it was all just a joke. The criticism, however, shouldn’t be that he didn’t get the joke – the criticism should be that he didn’t get the joke two decades too early. Dour Bond’s day had yet to come. There have always been two sides to Movie Bond. As Dalton pushed the needle to one end of the spectrum, anyone with a remedial knowledge of physics should have expected that it would return with an equal and opposite reaction. No matter the actor’s take on the role, Bond is best when he’s given time and space to be James Bond. Flash a knowing smile. Flirt with beautiful women. Drive a car none of us will ever own. Drink a martini with a brand of panache outlawed since the pre-code years. These favorite Bond tropes rarely propel a narrative, yet they are cherished and required. A Bond movie should be a playground of obstacles rather than an obstacle course where our hero is forced to connect the narrative dots as the crow flies.

In the history of the franchise, two directors have understood this concept perhaps more precisely than the others: Terence Young and Martin Campbell. Was it luck or skill that they hired the Kiwi, Martin Campbell, at precisely the right time to showcase their newly anointed Bond? He’d directed a trio of satirical sex comedies in the UK during the mid-70’s and had been toiling as a director on the BBC mini-series circuit, his most notable production the eco-thriller Edge of Darkness (co-starring, that’s right, everyone’s favorite MITCHELL!, Joe Don Baker). His one large-ish Hollywood feature had been the tepidly received Ray Liotta dystopian actioner No Escape. Of hiring Campbell, Michael G. Wilson said, “He’s… an excellent director when it comes to work with actors and he’s certainly good with action. He was a natural choice.” Was he? Admittedly I haven’t seen the lot of his BBC mini-series but permit me the assumption that he wasn’t directing bunch of ripping yarns over at the BBC. What I take away from Wilson’s statement is that they sought a director that concentrates on his actors – not one with a lengthy action resume – though they had to tout his action chops to appeal to a disenfranchised fan base.

Campbell himself expressed his own doubts about the continued viability of Bond and did not exactly jump at Wilson’s offer to direct. “I questioned whether Bond was part of the 90’s or an anachronism,” he said. “It was a question of deciding whether he was relevant or not, whether he could still be entertaining and successful as he had been in the past.” Sentiments that echoed a conflicted critical voice during the Dalton years. Dalton was well received but the films still seemed stale to critics and, as expressed by the small box office receipts, the fans as well.

The long respite between productions had one major unintended consequence. For a certain segment of Bond fans, GoldenEye became more than just another Bond movie. It was the thaw after a long winter, a catharsis if not a miracle. In the wake of Cubby’s housecleaning, the producers hired the director they thought would bring the Bond franchise back to the basics. Bond would again be, first and foremost, dashing actor in a fine tuxedo tempting danger and beautiful women in equal measure.

Micro-#Bond_o_nomics

I’d seen my first Bond in the theater – Licence to Kill – at age 11 and then poof. Nothing. I’m of course not paying attention to the behind the scenes drama. The business end was of no interest to me. I’m watching previews before other movies and I’m not seeing Bond. Soon I stopped looking. Six years to a teenager feels like eternity… enough time to dissolve passions and move on to the soup du jour. After getting hooked by The Living Daylights and bingeing on Bond between Dalton entries, I just stopped watching 007.

When the first GoldenEye trailers finally hit theaters, they immediately reignited my interest, the embers apparently still smoldering but never extinguished. I remember the anticipation. A new Bond. A Pierce Brosnan Bond. An actor I knew well from a beloved TV show, Remington Steele. The anointed one had finally earned his proper licence to kill. My anticipation for GoldenEye rivaled that of only a handful of movies in my life. The first Star Wars prequel (that shall remain unnamed). Back to the Future II. Terminator 2. Point being, this list is seriously short and littered with impossible expectations.

There’s one moment during GoldenEye that caused many members of that opening night audience to stand and cheer. Who cheers at the screen? Who feels compelled to stand and praise nothing more than light and shadow? 17-year-old me. And I think you know the scene to which I’m referring. Brosnan’s tank busts through a St. Petersburg wall in pursuit of General Ourumov and the kidnapped Natalya. The brassy Bond theme blares. The whole theater buzzed for minutes afterward. Electricity coursing through our collective veins as Brosnan pauses, the tank littered with rubble, to adjust his tie, nothing more. NOW THAT’S JAMES BOND, GODDAMMIT I wanted to yell. But that’s not my style. Instead, I went home and penned a review for my webpage. Clearly, not much has changed.

I saw GoldenEye on opening night in a theater full of easily entertained teenagers. The atmosphere boosted the experience. I didn’t give a lot of thought about how the movie had replaced Robert Brown with a female M or put the words “sexual harassment” on the lips of Moneypenny. The shifting sexual politics and post-Cold War attitudes were lost on me amongst the guns, girls and thrilling stunts. But it was all still Bond, the characters and events filling in largely the same blueprint. By this point in 1995, I’d begun co-writing a movie review website that had gained some notoriety (a feature in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, our reviews also ported over to MTV’s Adam Curry’s entertainment website. Adam m’f’ing Curry! exclaimed no one reading this essay). Sadly, all of our work has been buried in a Geocities-littered graveyard. I’d love to find the review I wrote for GoldenEye. To have that kind of insight into my own perspective, in the moment, right after watching the movie would be like peering into own my acne-scarred soul. I do, however, still have that movie ticket with the grade I bestowed: an A. I’m not sure I gave out anything higher.

But GoldenEye isn’t that perfect, of course.

The Q-branch scene feels a bit too jokey, like it was ripped from the depths of the Roger Moore-era. Without Moore’s hinged eyebrow and droll retorts, the comedy seems misappropriated on Brosnan (as did most of the Brosnan-era Q-Branch rundowns). Furthermore, the BMW 7 series car feels like a piddly roadster after already having watched the Aston Martin battle Xenia’s Ferrari for road domination.

There’s the pesky issue regarding Eric Serra’s controversial score, which, in my opinion, might be the most conspicuously dated in the entire series. Serra takes risks in updating Bond for the 1990’s but the score lacks the timeless classical orchestration that makes the Bond scores, John Barry’s in particular, so appealing fifty years in. Even Conti’s funked-up score for For Your Eyes Only borrowed heavily from prior Barry compositions despite its disco-decadent leanings. Meanwhile, Serra’s score felt stale within five years. The original version of the score lacked even Barry’s Bond theme. Producers hired John Altman (who had worked on the traditional symphonic arrangements with David Arch) to re-insert the Bond theme during the tank scene. The very scene that caused rapture, in part because of the appearance of the boisterous Bond theme, had originally been scored with Serra’s “A Pleasant Drive in St. Petersburg.”

Brosnan’s Bond also takes much abuse for being a walking, dogged cliché. And seeing as how this was part of the increasingly overt and pre-apologetic self-awareness, the Bond-bashing can be forgiven as they still had to work out a happy medium between emasculating their hero and merely poking fun at his chauvinism with a wink and smile. Furthermore, tracking the critical opinion of Brosnan’s Bond could result in whiplash. Though many lauded Brosnan’s reinvention and return to the character’s lighthearted frivolity in the face of extreme danger, some, like Tom Shone in the Sunday Times, called Brosnan “less a piece of casting and more a masterstroke of art direction… the man looks as though he was born to model jumpers.” Brigit Grant, Sunday Express Classic Magazine, said, “I was secretly pining for Sean Connery and felt that Brosnan was more of a Milk Try man who failed to deliver.” If I may be so bold as to interject my own thoughts with the benefit of hindsight… Brosnan’s plays GoldenEye safe. In the abstract, when I think of the generic Bond profile, it is Pierce Brosnan. And in GoldenEye he rarely uses the character to break free from our narrow expectations of what Bond should be. Bond is as Bond does. But because GoldenEye provides a slough of eccentric supporting characters (Robbie Coltrane, Minnie Driver, Joe Don Baker, Tcheky Karyo) and standout stunts and action set pieces, Brosnan’s to-the-letter performance never needs to take unnecessary risks. So while he might be little more than “art direction” in his first outing, Brosnan manages the film from within with workmanlike precision and easy-going whimsy. He grounds the audience in a Bond they know, a Bond they already love. It’s not until his subsequent missions as 007 that Brosnan makes the character his own, sadly, however, he’s overshadowed by diminished returns resulting from a misguided creative direction.

It’s the women in GoldenEye that ultimately provide the new direction when Bond doesn’t (or perhaps shouldn’t) dare. During Brosnan’s reign, women take an increasingly prominent role in the narratives on both sides of the aisle for better and worse. Bond’s relationship with Moneypenny (Samantha Bond), for example, feels more like a conversation between reconciled but combative divorcees as it tries to straddle both flirty innuendo and litigation.

Judi Dench’s M provides the film’s counterbalance to the hypersexualized sadism of Xenia Onatopp in GoldenEye. (One could make a case that Izabella Scorupco’s Natalya also contributes to the new Bond feminism, but I would argue that her character is merely an extension of an already established Bond girl archetype despite her “boys with toys” speech.) Michelle Yeoh, a kind of post-feminist action hero, works alongside Bond in Tomorrow Never Dies. These women are the reason that Denise Richards’ Christmas Jones in The World Is Not Enough feels so anachronistic in the context of this newly “enlightened” era. She acts as a callback to the rampant bimboism that marred the 1970’s-era Bonds like the rose on the broad backside of Jack Wade. Even within GoldenEye, Bond shamelessly woos a fawning MI-6 evaluator with both his driving and linguistic maneuvers. It is this seduction that incurs the wrath of M’s wicked tongue, which here famously calls Bond, “a relic of the Cold War, whose boyish charms, though wasted on me, obviously appealed to that young woman I sent out to evaluate you.” To which James replies, “Point taken.”

Old habits die hard, despite best better intentions.

The Choice of New Generation

(While I’m not holding out hope for some Pepsi money to help fund this project, product placement paid entirely for Tomorrow Never Dies… so why not #Bond_age_?)

Pardon the sweeping generalization, but Bond fans tend to gravitate toward the Bond that shepherded them through their youth. My nostalgia belongs to Dalton. And while I’m a steadfast critic of the latter Brosnans, I wholly defend his contribution to the series. He was better than the material he was given. He too shares a healthy chunk of that nostalgia.

On that night in November, now 18 years ago, I become hopelessly enraptured with GoldenEye. And even though time and distance have offered the opportunity to analyze the film with a more objective eye, I’m still thrilled by the tank scene, giddy every time Famke assaults Pierce in the Russian bath house (“No more foreplay”) and humored by pretty much every line spoken by Alan Cumming. Part of me will always be 17 and experiencing that film for the first time. For my generation and the half step behind, GoldenEye remains a watershed Bond, a Bond untouchable by the eroding waters of time.

The Bond generations on either side, however, don’t tend to hold GoldenEye in such high regard. They like it well enough, but it’s no Onatopp orgasm. Often it’s merely lumped into other good, but not great entries in the series. I’ve come to this realization after dozens (hundreds?) of conversations with the many passionate Bond fans on Twitter. And it actually came as quite a surprise to me, as I tend to wear my GoldenEye blinders. So let’s take a closer look, sans blinders, at how (or if) GoldenEye transcends the dogged formula.

Bond is again placed in the familiar role of champion and defender of England (and a broad Western ideology in general), a trend that dominated the Moore years. The three-girl formula remains in place. The villain, Alex Trevelyan (Sean Bean) wants to cripple London with an EMP, which, on its own would have been minor terrorist mischief compared to other Bond villain schemes… BUT just before detonation he’s going to steal millions of pounds from the Bank of London. It’s almost as if he threw that last bit in there to prove he wasn’t merely a closet nihilist. If I break this down according to the Underpants Gnomes’ guide to profitability:

Step 1: Detonate EMP in London

Step 2: ???

Step 3: Profit

Compare this to Auric Goldfinger’s plan.

Step 1: Blow up Fort Knox

Step 2: ???

Step 3: Profit

Or Max Zorin’s.

Step 1: Sink Silicon Valley

Step 2: ???

Step 3: Profit

That the villain was once a 00-agent working with Bond provides the new twist – a history, a friendship even, dissolved by treasonous action against Bond’s beloved England. This preface to the Bond/adversary relationship re-orients our expectations; Bond villains traditionally appear from the shadows, bearing megalomania or personal vendettas that incur the wrath of James Bond. Other than the botched Blofeld narrative and perhaps the (temporarily?) abandoned Mr. White saga of Casino Royale and Quantum of Solace, Bond’s villain rises and falls within one timline. GoldenEye creates a greater sense of depth by giving Bond and his opponent shared backstory before advancing the story nine years. Even the duration of the gap between Trevelyan’s betrayal and the GoldenEye narrative proper seems to have been chosen specifically to appeal to the subconscious of the Dalton denier. Nine years places the pre-title sequence before The Living Daylights and before Dalton – as if the filmmakers had rewritten Bond’s history, erasing Dalton altogether. It’s not out of the question. The franchise has a history of apologizing for box office failures with selective memory. Diamonds Are Forever wholly denies the existence of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service by recasting Connery and never addressing the monumental, Bond-shaping events that conclude the prior film.

GoldenEye manages to portray Trevelyan’s scheme as slightly more altruistic by pitting him as an ideological adversary when he’s really no better than any of the other panhandlers that have come before him. They beget an elaborate scheme for the sake of cold, hard cash. (Also, Trevelyan’s scheme doesn’t particularly make sense. If you render the Bank of London irrelevant, where are you going to spend those British pounds? Could you convert it? If it were that easy to convert massive amounts of cash, the Chinese would have unloaded all those American dollars years ago. The one economy that would take those pounds has just been destroyed. But I digress.) That the villain and Bond have history does ultimately divert the narrative. When you take Trevelyan’s scheme at face value, his goals bear much resemblance to other prominent villains, and Bond reacts according to standard operating procedures. Their relationship benefits GoldenEye through glorious tête–à–tête, speechifying and combative one-upmanship that stops just short of “whipping ‘em out.”

Vintage Bond

While we were all marveling at Bond’s ideological and aesthetic “progress” made to adjust to a new era or perhaps merely glad to have Bond back in the saddle, we overlooked the fact that GoldenEye is still, behind all the updates and spectacular stunts, a boilerplate Bond. And let me stress that this is not a criticism. Some of the best Bonds have been boilerplate, all the same Bond elements, assembled according to the Goldfinger model, rearranged and given a cracking new coat of paint. In Licence to Thrill, James Chapman calls GoldenEye and the other Brosnan Bonds “old wine in new bottles.” Despite the overhaul, despite the newly minted M and Moneypenny, a new CIA contact replacing Felix Leiter, Brosnan, the larger budget, GoldenEye tells a traditional Bond tale ripped straight from the time-tested formula.

Consider the following: The Spy Who Loved Me was the Goldfinger for the Moore generation. And the movie that established the boilerplate: Goldfinger was the Goldfinger for the Goldfinger generation. (Consistency sacrificed for the sake of repeating Goldfinger as many times as possible.)

Thus, GoldenEye becomes my generation’s Goldfinger. Both films are flawed and arguably held in too-high regard as a result of rampant nostalgia and Bond-colored goggles. Not that there’s anything wrong with that. I’ve written about nostalgia’s role in Bond appreciation; there’s no reason to discredit nostalgia when discussing the value of an individual film from a historical perspective. The popularity of Goldfinger catalyzed the Bond franchise. GoldenEye defibrillated Bond when his pulse slowed, taking in $357million worldwide, more than The Living Daylights and Licence to Kill combined. As a result of GoldenEye’s success, CBS purchased the rights to broadcast Tomorrow Never Dies for $20million even before the film’s release. If there were any doubts about Bond’s contemporary financial viability, GoldenEye crushed them like a Canadian admiral between the thighs of Xenia Onatopp.

What the behind-the-scenes fiasco and timidly launched production of GoldenEye shows, most readily, is that the Bond 17 production team understood the importance of the task. The project would not be rushed. Scripts were written and then rewritten at the last minute. Consider the tank scene one more time. Eric Serra’s score had been an entirely new composition with little callback to the past. For that moment in time, the score achieved the production’s stated goal: modernization, a melding of James Bond and the contemporary music of the early-to-mid 90’s. But in the 11th hour, the Bond producers decided that the scene necessitated more overt familiarity. Even as they endeavored to update Bond for a new cinematic era, the weight of Bond’s past could not be dispatched entirely. Old Bond fans and new Bond fans needed to experience that synesthesia of sight, sound and nostalgia that can only happen in a movie into which most everyone enters with pre-existing knowledge. They brought back the old Bond theme to punctuate that now legendary scene. GoldenEye may not have been a perfect Bond, but we should all be thankful that in this specific moment, at crossroads for the franchise, EON got it nearly, almost completely, entirely right.

Special Edition Deleted Blurbs:

It wasn’t just the film’s success that catalyzed GoldenEye’s broad appeal. The video game of the same name was released for the Nintendo 64 game console in August of 1997 and went on to sell 8 million copies worldwide (making it the third best-selling N64 game behind Nintendo’s own titles behemoth kid-friendly titles Super Mario 64 and Mario Kart 64). While the game pioneered many now commonplace features such as varied mission objectives and stealth elements, GoldenEye 007 will forever be remembered for the multiplayer mode that pitted up to four players against each other in an arena-style deathmatch. Players could choose to play as a number of familiar Bond faces, including Oddjob and Nick Nack, in addition to the main characters from GoldenEye. Weapons ranged from Bond’s PPK to throwing knives to Scaramanga’s golden gun (one shot kills!). The game proved that consoles could be a viable venue for a first-person shooter, breaking from the notion that first-person shooters were strictly PC-gamer experiences. The game became an obsession and maintains popularity even today, a common fixture on many “best game lists.”

It was rare for someone to not be playing GoldenEye 007 somewhere on my freshman hall in 1997. Grades suffered, much sleep was lost. Nick Nack was banned from more intense games because the little bastard was so hard to shoot. (It wasn’t a written law, but rather vigilante justice. You were deemed a punk for picking him, and everyone would gang up against you.) The release of the game would have coincided nicely with the release of the VHS home video release for GoldenEye, further spurring sales of both. I can’t help but attribute some of the film’s lasting appeal to that generation of gamers that made GoldenEye 007 one of the most popular and influential video games in history.

Previous James Bond #Bond_age_ Project Essays:

Dr. No / From Russia With Love / Goldfinger / Thunderball / You Only Live Twice / On Her Majesty’s Secret Service / Diamonds Are Forever / Live and Let Die / The Man with the Golden Gun / The Spy Who Loved Me / Moonraker / For Your Eyes Only / Octopussy / A View to a Kill / The Living Daylights / Licence to Kill / GoldenEye / Tomorrow Never Dies / The World Is Not Enough / Die Another Day / Casino Royale / Quantum of Solace / Skyfall